Which language does Santa speak?

If, like me, you used to expectantly write a long list of improbable demands to Santa each year as a child, you’ll be curious to know what happened to those letters. Oddly enough, it never ever occurred to tiny Nat to question where the (probably unaddressed, definitely unstamped) letter went once it dropped into the post box: after all, if Santa was so magical then he’d surely have solved the small problem of how to access my very important letter.

But when I was recording Greenlandic recently for uTalk and doing some research on the country, I was intrigued to find that my letters actually may have reached Santa, and that he lived in Greenland. Until 2002, letters to Santa from all over the world would collect in a giant red post box in Nuuk and – here’s the exciting part – if they had a return address they’d be replied to by Santa himself (or an elf).

Sadly, Santa went bust in Greenland, and although letters may still end up there, they won’t be processed or answered. But, being super Santa, he obviously had a back-up plan and didn’t just run things from Greenland: Santa has operations going in Iceland, Sweden and Finland too. In fact, all of Scandinavia claims to be Santa’s home, raising the interesting question of which language Santa speaks.

Of course, we all know that Santa travels around the whole world on Christmas Eve and must therefore be fairly proficient in various world languages (he’s probably been dabbling in uTalk‘s Directions topic, available in 128 languages, to help him find his way), but just to prove it, his operation in Finland, still going strong, will reply to letters in up to 12 different languages from around the world. So Santa’s clearly at least a dodecalinguist!

Why not try to be a bit more like Santa this year and learn a new language? You could start off for free with the January uTalk Challengeand, if you really want to emulate Santa, go for the 12 month language challenge. Complete a language by the end of the month, and we’ll give you another free uTalk Essentials for a new language the following month.

Merry Christmas!

Nat

To tip or not to tip?

A social dilemma you’re bound to fall into at some point is whether or not to tip – and how much! Tip too little and you risk the waiter chasing you down the street shouting abuse; tip too much and you might gravely offend the staff. Tipping customs vary all over the world, between different countries and regions (not to mention situations), so do your research before you travel!

How much should you tip?

In the USA, tipping is mandatory and fairly high, with 15-20% being expected. Service wages are fairly low, meaning people factor tips into their pay, and waiters will ask you where their tip is if you haven’t left one.

In the UK, tipping is more relaxed and is never really expected in a pub or cafe, or anywhere with self-service. In restaurants, 10% is usually expected, but if you feel the service was poor then you can express this by not leaving a tip.

Move into Romania, however, where 10% is also recommended (more if you’re really happy with the service), and not leaving a tip would be considered very rude: do not try to return to a restaurant where you didn’t leave a tip.

Drinking tips

In lots of countries in Europe, the traditional attitude towards tipping can be seen in the language: German ‘Trinkgeld’, Swedish ‘dricks’ and Danish ‘drikkepenge’ all mean ‘money for drinking’, as does the Slovak ‘prepitné’, French ‘pourboire’, Slovenian ‘napitnina’, Serbian ‘напојница’ and Croatian ‘napojnica’. The idea behind this is that you just round the bill up or leave a few coins, as a contribution towards a drink for the waiter.

Further East, the direct translation is even more specific: in Russia, you leave money ‘for tea’ (‘чаевые’). The same is true of Kazakh‘s ‘шайлық’ (шай- shai- tea’), Uzbek‘s ‘чойчақа’ and Tajiki‘s ‘чойпулӣ’).

Beware, however, that tipping practices have changed significantly and just a few coins often won’t cut it any more in these countries: be prepared for at least a 10% tip, as a broad guideline.

When not to tip

So far, the problem has only been how much to tip, and if you’ve accidentally tipped too much in America or Europe, it won’t cause any massive problems. But in some areas the attitude towards tipping changes drastically.

In Malaysia, Singapore and Japan tipping is not practised at all and could be considered odd or even offensive.

In Georgia, it can be seen as an affront to the notion of hospitality. Beware as well that a tip can easily be misconstrued as a bribe, which you definitely don’t want to get in trouble for, so make sure you look up before travelling whether tipping is normal practice in the country you’re visiting!

Have you ever been caught out by tipping etiquette?

Nat

Can you whistle a phrase?

A few days ago, Gloria stopped by my desk with a burning question: had I ever heard of the whistling languages?

Proudly, I was able to answer that I had, but quickly became deflated when we realised that neither of us had the slightest idea of how they work. Was there a whistling alphabet with different tones for vowels and consonants? Do you just learn whole phrases by heart for limited daily use? Clearly there was a very large hole in our knowledge, and we immediately set about trying to fill it in.

For those of you who don’t know what we’re talking about, whistling languages are those which have developed (mostly) in areas of extreme terrain, where communication by speech would be impossible but where whistles can carry over large distances (up to a couple of miles). Perhaps most well known is the whistling language Silbo Gomero (of La Gomera) which, once endangered, is now being successfully preserved through mandatory classes at school. The way the language actually works is that the whistled phrase resembles, in intonation and pitch, the phrase in the original language – Spanish, in this case. This means that users can improvise conversations in the same way as with a spoken language, even using modern vocabulary which may not previously have existed.

Gloria has actually been to La Gomera and seen first-hand how they achieve the incredible variations in the whistling language: not just with pursed lips, but with fingers to amplify the sound and change the tone. This is all very impressive to me, but it turns out that Gloria is a bit of an expert at whistling, and graciously offered to demonstrate a few simple techniques. Although it’s not the same as having a whole, developed whistling language at your disposal, she does have a few ‘set phrases’ which she not only uses in specific situations but which are understood by people and – in one case – birds too! Watch to the end to hear her top tip on how to make your whistles extra loud…

If you think you can rival Gloria for expertise in whistling, or have a different whistle you actually use in everyday life, we’d love to hear about it!

Nat

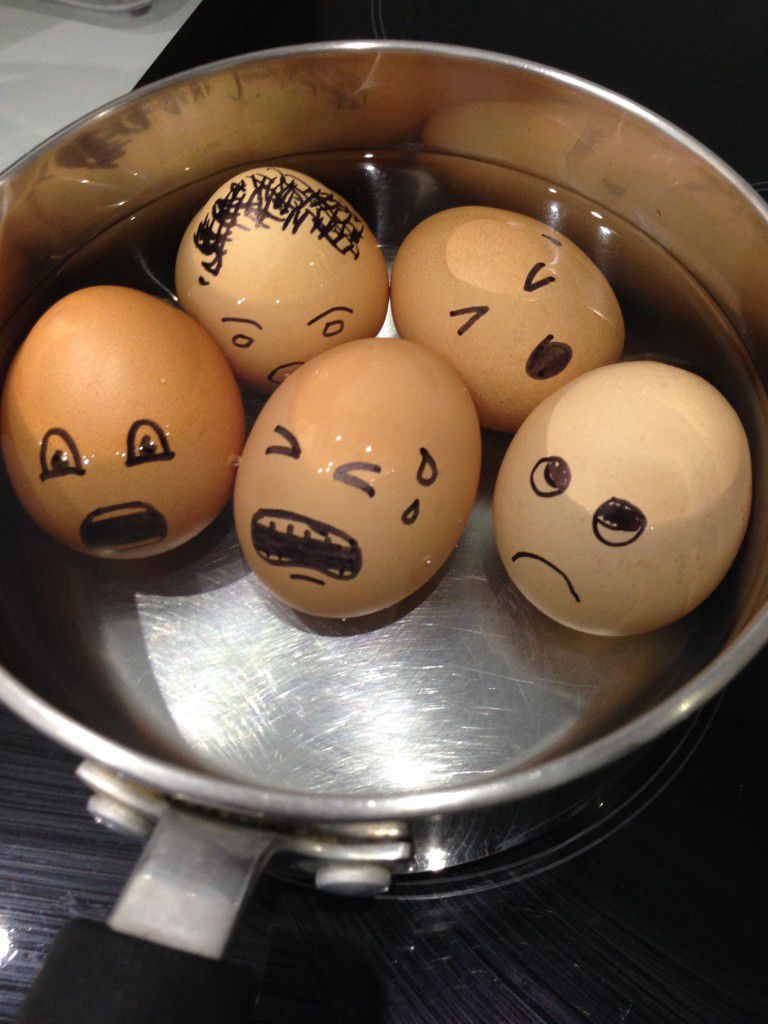

Lost, drowned, in a shirt… how do you like your eggs?

Happy World Egg Day!

English is quite a boring language when it comes to eggs. We boil them, scramble them, poach them, fry them. All very ordinary.

Which is why we were delighted to discover that other languages are more dramatic in their approach to eggs!

Over to Italy:

For Italians, poached eggs are literally ‘eggs in a shirt’ – ‘le uova in camicia’ – possibly because the frilly poached egg white looks like the sleeves of a loose blouse.

Alternatively (but still quite theatrically), you can call them ‘le uova affogate’ (literally ‘drowned eggs’). Poor old eggs!

And now to Germany:

Maybe it’s the same idea of drowning that makes Germans call their poached eggs ‘verlorene Eier’ – ‘lost eggs’. The eggs, like sailors lost at sea, drown quietly in the saucepan.

Or, if it’s a fried egg you’re after, the Germans have a pretty expression for that too: ‘Speigeleier’, literally ‘mirror eggs’. Can anyone tell us why..?

Bullseye!

In Italian, Slovak and Czech (to name but a few), the fried egg is the ‘bullseye egg’- because, of course, it resembles a bullseye (or a porthole, which is the same word): ‘le uova all’occhio di bue’ (Italian), ‘volské oko’ (Slovak), ‘volská oka’ (Czech).

Eyes in a pan?

A similar idea, though slightly more graphic, applies in Bulgarian and Slovenian where the fried eggs (‘яйца на очи’ and ‘jajce na oko’ respectively) translate as ‘eggs eye-style’! So next time you fry an egg, you may choose to remember this vocabulary by imagining a big eyeball staring up at your from the plate… OR you may choose to stick to the safe, if rather boring, English equivalent.

Got any other interesting egg-related vocabulary? Let us know!