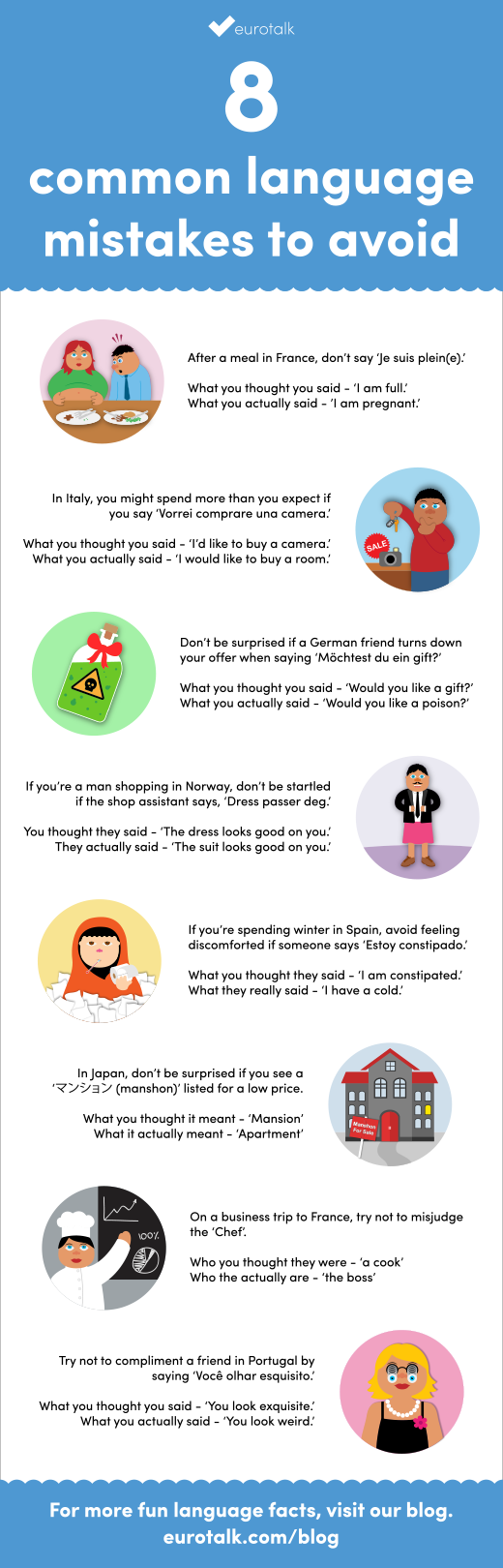

8 common language mistakes to avoid [infographic]

When you’re learning a new language, it’s easy to make mistakes. And that’s ok; it’s the best way to learn. But sometimes you might think you know what you’re saying, and actually you’ve said something very different. Here are a few examples to look out for…

Please let us know your own examples and as always, do feel free to share the infographic with others.

Infographic created by Adam (research) and Luke (design)

Embed This Image On Your Site (copy code below):

Languages for the future: the top ten

A recent report by the British Council has laid out the ten most important languages for the UK’s future, in political, economic, educational and cultural terms.

According to the report, the ten most important languages, in order, are: Spanish, Arabic, French, Mandarin, German, Portuguese, Italian, Russian, Turkish and Japanese. I read this list with a certain amount of smugness that I speak Spanish, German and French – although my knowledge of key languages such as Mandarin and Arabic is, sadly, next to nothing. So feel free to give yourself a pat on the back if you can speak, or are learning, one of those ten languages.

Unfortunately, the report also indicated that the numbers of UK residents actually learning these languages, especially the ones not taught in schools, are very low. On a positive note, around 15% of people can hold a conversation in French. However, only 6% are able to do so in German, 4% in Spanish and 2% in Italian. But the figures for the other languages are as low as 1%.

Unfortunately, the report also indicated that the numbers of UK residents actually learning these languages, especially the ones not taught in schools, are very low. On a positive note, around 15% of people can hold a conversation in French. However, only 6% are able to do so in German, 4% in Spanish and 2% in Italian. But the figures for the other languages are as low as 1%.

Perhaps one of the problems is that Mandarin, Japanese, Russian and Arabic all require learners to pick up another script. This might seem daunting, but is actually really exciting. Just being able to read simple words in another script gives you a huge sense of achievement, and you’d be surprised how quickly you can begin to decipher words from what previously looked like squiggles.

Hopefully if you’re reading our blog you already know the importance of language-learning, and that picking up a new language is an adventure rather than a chore! But maybe this list will give you an idea about which language you fancy picking up – maybe it’s time to start reviving your A-level French? Or be brave and give Arabic a try? Personally, I’m working on adding Italian to my list, which is proving interesting as I lapse back into Spanish as soon as I don’t know a word!

The report recommends a much greater focus on languages in schools and that businesses should invest in language training for languages that are useful in their industry. But don’t worry if your school days are behind you – it’s never too late to learn a new language!

Alex

What language is spoken in France?

A quick quiz question for you: what language is spoken in France?

Answer: well, French of course! But did you know France is also home to several small regional languages, including Alsatian, Catalan, Breton and Occitan?

Like many other European countries, the French once spoke a wide range of regional languages and dialects. However, during the Third Republic, the French government made French the only official language, and outlawed use of regional languages such as Breton and Occitan in schools and institutions. The underlying idea of creating national and linguistic unity may have been well-intentioned, but as a result, most of these regional languages are now endangered.

Like many other European countries, the French once spoke a wide range of regional languages and dialects. However, during the Third Republic, the French government made French the only official language, and outlawed use of regional languages such as Breton and Occitan in schools and institutions. The underlying idea of creating national and linguistic unity may have been well-intentioned, but as a result, most of these regional languages are now endangered.

Nowadays, Occitan is spoken by around 1.33% of the population (in the Occitania region in Southern France), whilst Breton is spoken in Brittany by around 0.61% of the population. These languages are recognised by the government, but not considered official languages, and therefore given minimal support and opportunity for use.

The situation is a little more encouraging in Spain, where Basque, Catalan, Valencian and Galician are recognised as co-official regional languages, and a thriving community of native speakers exists in each of these regions.

This rather cool map shows how the areas over which each of these languages is/was spoken has changed over the last 1,000 years.

Over time, due to globalisation, mass media and government drives for national unity, the national languages in Spain, France and many other countries have established dominance and pushed smaller regional languages onto the sidelines. However, there are still communities of native speakers of each of these languages, and many people are passionate about passing on the language and culture of their region to the next generation.

Regional languages are often closely tied to the culture and identity of a region: the Catalonians I know are proud Catalan speakers, and often much of an area’s history, literature, music and so on is written in the regional language. These languages may be small, but they are certainly worth learning and preserving!

In fact, we have produced our Maths, age 3-5 and 4-6 apps in both Basque and Catalan, and uTalk is currently available in Galician, Basque and Catalan. And for anyone interested in regional French languages, why not learn a few phrases for free in Occitan, Breton, Alsatian or Provencal?

Alex

The uncertain nationality of The Artist

On 26th February, The Artist swept the board at the Academy Awards, winning five of the twelve categories it was nominated for. This included Best Picture, Director (Michel Havanavicius) and Actor (Jean Dujardin).

However, something has bothered me since the release of this picture.

It is a film with French actors in the two leading roles, made by a French director and with the support of several French film studios. Yet it is a ‘silent’ film and any dialogue from the characters – audible or otherwise – is in English. So with this in mind, can The Artist count as a foreign language film?

It is a film with French actors in the two leading roles, made by a French director and with the support of several French film studios. Yet it is a ‘silent’ film and any dialogue from the characters – audible or otherwise – is in English. So with this in mind, can The Artist count as a foreign language film?

At first glance, it is easy to assume it cannot. The film features English as the ‘main’ language and the characters appear to speak, albeit muted, English dialogue.

But that’s only to the perspective of English-speaking audiences.

News reports on The Artist’s success at award ceremonies describe it as the most awarded French film in history and, at the 2012 César Awards (their equivalent of the Academy Awards), it won the award for Best Film, yet English-speaking films such as Black Swan and The King’s Speech were seen as foreign language films.

To me, it seems confusing that it can be seen as both an American and French film, but how can you define a film, which can only be surely described as ‘silent’ – a genre that hasn’t been on our screens in over 70 years?

The Artist has been seen as Havanavicius’s homage to silent cinema and as a result, it has revitalised the genre for a new generation. Can silent films make their way in the world, or will language be the key player in a film?

Katie

French – champion of the language learning world?

I remember the moment when we knew we were officially grown up in primary school – during French lessons with the headmaster.

MFL lessons are the norm nowadays but back in my time, French lessons were a weekly highlight, as they meant me and about a dozen classmates spent half an hour learning something the rest of the school did not already know.

As I moved onto secondary school, languages were eventually deemed ‘uncool’ and those who took French or Spanish past GCSE – myself included – were thought to be insane by their peers.

When I think about it, only French got a shoo-in at primary school. Spanish was introduced in the first year of secondary school but even then, all efforts were concentrated on learning and teaching French.

No-one seemed to care about German or Italian and everyone thought Mandarin was a fruit.

This makes me wonder – when did French become the ‘go-to’ foreign language at school?

This makes me wonder – when did French become the ‘go-to’ foreign language at school?

Learning French is a current requirement in UK primary schools and the possibilities of school trips, exchanges and overseas partnerships are endless, but knowing how to speak it may not be as impressive as learning more obscure languages such as Swedish, Polish or Japanese.

The number of people learning a language nowadays relies on how influential it is in popular culture – just look at how many people have started to learn Na’vi, just because it was featured in James Cameron’s 2009 epic Avatar – and this can only be aimed at the younger generation, when ‘cool’ is key.

This is the aim of our annual language competition for primary schools, the Junior Language Challenge. Parents have commented that the competition has fuelled their children’s passion for learning new languages and has inspired them to take up different ones as options for GCSE.

I am hopeful that more unusual languages will be featured in the National Curriculum, but unless Justin Bieber turns around and starts learning Mandarin, whether pre-teens take language learning to the next step is debatable.

Where do you think today’s language learning is going? Where can there be room for improvement? And ask yourselves, in ten years or so, will French reign supreme or can Spanish or Mandarin take the crown as Most Popular Foreign Language to Learn at Primary School?

Katie