5 times you spoke Italian and didn’t know it

Did you know that you speak Italian?

No, really – you do. And we don’t just mean that time you ordered a pizza. Here are a few words you’ve probably used at some point, but might not have realised were Italian:

Novella

Longer than a short story, but not quite a full novel. Well-known novellas include John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis) by Franz Kafka and Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decamerone (The Decameron). The word ‘novella’ comes from the Italian meaning ‘new’.

Paparazzi

The use of this term to describe photo-journalists who follow and take pictures of celebrities can be traced back to a character in Federico Fellini’s 1960 classic movie, La Dolce Vita. Reports vary as to why Fellini chose this name for the independent photographer in the film, but one version of events claims it’s a word from an Italian dialect describing the annoying noise made by a small insect.

A cappella

Anyone who’s seen Pitch Perfect will know that a cappella means singing without any musical accompaniment, but its literal meaning in Italian is ‘in the manner of the chapel’. And it’s not the only Italian word used in music; the list is seemingly endless but a few examples are piano (quiet), allegro (lively and fast), crescendo (getting louder) and lacrimoso (sad).

Tarantula

The first spiders to be called ‘tarantulas’ were named for the Italian city of Taranto, where they were first found. Interestingly, these weren’t the hairy beasties we call tarantulas today, but what are now known as wolf spiders. (Not that we’d want to find either of them in our house.) Many people in southern Italy during the 16th and 17th century believed that a bite from the spider would cause a hysterical condition called tarantism, which could only be cured by dancing the tarantella.

Graffiti

Graffiti comes from the Italian word ‘graffito’, which means ‘scratched’, and in art history the term is used to describe work created by scratching designs onto a surface. The word dates back to the 19th century, when it was used to describe inscriptions and drawings found in the ancient ruins of Pompeii, and today has taken on a mostly negative connotation – no matter how skilful the artist, graffiti is generally considered synonymous with vandalism.

There are plenty more examples of Italian words that have found their way into other languages – among them:

Stiletto: from the Italian word ‘stilo’, meaning ‘dagger’.

Mafia: its origins are uncertain, but many believe it to be from the Sicilian word ‘mafiusu’, which means ‘swagger’ or ‘bravado’.

Extravaganza: a spectacular theatrical production, which takes its name from the Italian word ‘stravaganza’ (extravagance).

Quarantine: derived from ‘quaranta’, the 40 days of isolation required to try and halt the spread of the Black Death in the 14th century.

How many Italian words have you used recently…?

Language of the week: Italian

Buongiorno!

Italian is our language of the week, in celebration of an annual tradition, Il Palio, which dates back to the 12th century and is held on the 16th of August.

This is a horse race unlike any other, and is all over in 90 seconds. It’s held in the beautiful city of Siena, where the 17 districts compete against each other for the glory. Amazingly a district can still win if the horse loses their jockey during the race, as long as they’re over the finish line first (this has actually happened 23 times since records began). If you have a chance to visit Siena while the Palio is on, you should go – the main square is filled with flags from each district and there is an incredible atmosphere throughout the whole town.

This is a horse race unlike any other, and is all over in 90 seconds. It’s held in the beautiful city of Siena, where the 17 districts compete against each other for the glory. Amazingly a district can still win if the horse loses their jockey during the race, as long as they’re over the finish line first (this has actually happened 23 times since records began). If you have a chance to visit Siena while the Palio is on, you should go – the main square is filled with flags from each district and there is an incredible atmosphere throughout the whole town.

If you want to see just how much the Palio is celebrated in Siena have a look at this…

Here are some of the best things we’ve discovered this week about Italian:

- One of the longest words in Italian is ‘precipitevolissimevolmente’ which means ‘extremely quickly’.

- This Italian tongue twister: ‘Trentatré Trentini entrarono a Trento, tutti e trentatré trotterellando’… which means ‘thirty three Trentonians came into Trento, all thirty three trotting.’

- The word ‘Gelato’ means Italian style ice cream (different to normal ice cream for a number of reasons; firstly it is made with a higher proportion of milk to cream, secondly it has a slower churning process and finally it is served at a slightly warmer temperature than ice cream). Gelato is potentially one of the most important words to know in Italian, as the ice cream cone is an Italian invention and Italy is famous for its Gelato. There’s even an ice cream university in Bologna (Carpigiani Gelato University).

- Italian is a Romance language, meaning it has a Latin origin. Gesture could also be considered important to the Italian language, as messages are often conveyed using hands and facial expressions. When in Italy, you’ll probably hear people saying ‘Ciao Bella!’ to each other as a friendly greeting – but if you don’t want to be too familiar, you may wish to stick to ‘Buongiorno’ (good day) the first time you meet someone.

- The Italian alphabet has twenty-one letters in it. It does not include the letters J, K, W, X and Y; these letters can only be found in foreign words that are common in everyday Italian writing.

- To wish someone good luck in Italian, you should say, ‘In bocca al lupo!’, which translates literally as ‘In the mouth of the wolf’. The correct response to this expression is, ‘Crepi il lupo!’, which means ‘May the wolf die!’

Do you have a favourite Italian word or phrase? We would love to hear from you, so feel free to comment below, tweet us @EuroTalk or write to us on Facebook! And if you’d like to learn some Italian, why not try our free demo, or download our uTalk app to get started.

Alex

Why I’m learning Italian in January

So I’ve jumped on the bandwagon and I’m taking part in the New Year uTalk challenge too.

It took me a while to finally decide on Italian. I was going to attempt Arabic or Mandarin; however given the time frame of just one month, I thought the challenge would be too great for myself. However I will attempt either Arabic or Mandarin at some point next year, you can hold me to that!

So why Italian I hear you say? Well there are many reasons.

I often go skiing in Italy and it’s very different to skiing anywhere else in Europe, as not many people speak English. It can be quite a struggle sometimes, so hopefully by the end of January with my newfound Italian it should be a breeze.

Near the office there is an Italian delicatessen, which sells some seriously good food. When you enter they’re always talking to you in Italian, and as I speak none I feel slightly embarrassed that I can’t respond in their own language. My goal by the end of January is to be able to order my food in Italian, as well as have a conversation with the employees there.

My final reason is that there are many beautiful cities that I wish to visit over the next few years in Italy. Even though it is a given that I will do the ‘touristy’ things whilst I’m there, I would also like to think I may be able to go off the beaten track and find some true wonders hidden from the tourists. I also don’t want to be a typical tourist and ignore the locals; I want to be able to interact with them and get a real feel for the city.

So those are my reasons for learning Italian.

Anyone else going to join me?

Amy

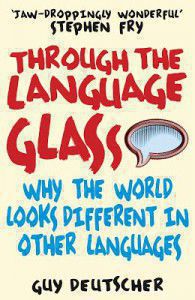

Book review: Through the Language Glass

Ever wondered what us language geeks do for fun in our spare time? Reading books about languages, of course! Well, not all the time – but I recently read the very interesting Through the Language Glass by Guy Deutscher, and would recommend it to anyone else who is interested in how different languages work, and how our mother tongue affects our thoughts and behaviour.

Through the Language Glass is all about the ongoing linguistic debate about whether our native language affects our perception and the way we think about the world around us. A large portion of the book is dedicated to a rather in-depth discussion about the differences between colour vocabulary in various languages. You might already know that Russian and Italian have two words for ‘blue’ (light and dark blue). But you might not know that the famous Greek writer Homer didn’t have any words for blue, and instead used mostly red and black to describe the scenes of the Iliad. This led to a long debate about whether people in the past lacked our modern ‘colour sense’ and saw the world in only a few shades. You’d probably have to be pretty dedicated to trying to understand the evolving debate on the development of linguistic terms for colours to plough through this rather long section, but it is rather interesting if you’ve got the patience.

Through the Language Glass is all about the ongoing linguistic debate about whether our native language affects our perception and the way we think about the world around us. A large portion of the book is dedicated to a rather in-depth discussion about the differences between colour vocabulary in various languages. You might already know that Russian and Italian have two words for ‘blue’ (light and dark blue). But you might not know that the famous Greek writer Homer didn’t have any words for blue, and instead used mostly red and black to describe the scenes of the Iliad. This led to a long debate about whether people in the past lacked our modern ‘colour sense’ and saw the world in only a few shades. You’d probably have to be pretty dedicated to trying to understand the evolving debate on the development of linguistic terms for colours to plough through this rather long section, but it is rather interesting if you’ve got the patience.

The rest of the book moves on to some interesting discussions of smaller tribal languages in Australia and elsewhere, and how their unique features either reflect the requirements of the society/location, or affect the behaviour of the speakers. For example, the Aboriginal language Guuguu Yimithirr has no words for left and right. Instead, speakers must develop an acute sense of North, South, East and West, as it’s impossible for them to say ‘the tree is on my left’ – instead they must say ‘the tree is North of me’. Experiments have shown that even if speakers of the language are driven to new locations blindfolded, they retain their incredible sense of direction and can still describe location based on the compass directions.

And how about grammatical gender? For us English speakers, referring to a table as ‘she’, as a Spanish speaker would (la mesa), or a girl as ‘it’, as a German would (das Maedchen), seems rather odd. But for most Europeans, using a blanket ‘it’ for everything doesn’t really feel right either. So what does this mean for all those speakers of languages with grammatical gender? Do they somehow see a table as girly and feminine, and a phone (el teléfono in Spanish) as macho and masculine? Well of course not… that would be silly! But there may be subtle ways in which these distinctions affect us. Think about how we can tell a story in English being vague about the gender of the person involved. Yesterday, I had dinner with my friend. Whether that friend is male or female is none of your business! But in Spanish, you’re rather forced to disclose that ‘la amiga’ was of course a girl.

We might find the idea of a ‘gender’ for inanimate objects strange and funny, but Deutscher traces this back to at least an original logical starting point. It might surprise you to know that there are many more genders in language, beyond the masculine, feminine and neutral genders you might already know. Some languages even have a ‘vegetable’ gender, which even includes things like aeroplanes. Why, you might ask? Well, it’s simple really. The ‘vegetable’ gender may have started off for only plants. This would have included wood, and anything made from wood, such as a boat, perhaps. It’s then not such a jump to having other vehicles in the same gender.

If any of this sounds intriguing and you’d like to know more, I recommend that you pick up Deutscher’s book. It’s not quite beach reading, but it’s accessibly written, not an academic tome that’s only for linguists. I can guarantee that you’ll learn something new about languages and maybe gain a different perspective on how your native language affects your perception.

Alex