Just how bad was Mark Zuckerberg’s Mandarin anyway?

A couple of weeks ago, Mark Zuckerberg shocked the world by taking part in a 30-minute Q&A session in Mandarin Chinese. And we were all super impressed.

It was obvious, even to a non-Mandarin speaker, that he wasn’t completely fluent, but he managed to keep going for almost the full half hour, and his audience at Tsinghua University in Beijing seemed to enjoy his jokes, and his efforts at speaking their language. And it all sounded pretty good to me.

Which just goes to show how much I know. Not too long after the video appeared online, Isaac Stone Fish, Asia Editor at Foreign Policy Magazine, gave his assessment of the Facebook CEO’s efforts: ‘in a word, terrible’. The headline of the piece was, ‘Mark Zuckerberg speaks Mandarin like a seven-year-old’. Ouch.

Since the article was published, people have been jumping into the debate left, right and centre with their own opinions on how he did. James Fallows, writing for The Atlantic, said that Zuckerberg spoke Mandarin ‘as if he had never heard of the all-important Chinese concept of tones’, whereas Mark Rowswell, a Canadian comic who’s fluent in Mandarin and famous throughout China, took to Twitter with a more balanced view.

To clarify, Mark Zuckerberg's Chinese isn't very good. He's incredibly fluent for a Fortune 500 CEO. Which angle do you choose to take?

— 大山 Dashan (@akaDashan) November 1, 2014

Meanwhile, Kevin Slaten, program coordinator at China Labor Watch, was more concerned about the message being given out by Stone Fish’s article. Mark Zuckerberg, after all, is used to bad press and is hardly likely to be put off by a few negative comments. But Slaten looks at the bigger picture: ‘What is Stone Fish, a “China expert”, telling these students of Chinese when he is tearing down a notable person for speaking non-standard Mandarin? He’s telling them, “you’ll be laughed at”’.

Personally, I don’t know how good Zuckerberg’s Mandarin was. It sounded good to me, and as someone who really struggles with nerves when speaking another language, especially to native speakers, I’m pretty much in awe that he had the confidence to give it a go, particularly since it was a Q&A session, not a prepared presentation. (Not that I think Mark Zuckerberg is particularly short on confidence, but you know what I mean.) Had the audience sat there shaking their heads, looking confused or angry, things might be different, but they clearly appreciated the effort he’d put in, so who am I to judge?

Making mistakes is part of learning a language. Everyone has a funny or embarrassing story about a time they used the wrong word, or – in the case of languages like Mandarin or Thai – got the tone slightly incorrect and ended up saying something completely different than what they intended. There’s no shame in it, and in my experience, people appreciate the effort made. Mark Zuckerberg didn’t have to do that interview in Mandarin. He could have done what was expected of him and spoken English. And maybe he messed it up, but I bet everyone in that audience went home with a smile on their face (even if it was more from amusement than anything else).

Isaac Stone Fish has since responded to the criticism of his criticism, stating that his issue was with the media outlets who described Zuckerberg’s Mandarin as fluent, when it wasn’t. Which is fair enough, and maybe some of his comments were taken out of context, but I think the main point stands.

There’s a quote by Abraham Lincoln: ‘Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak out and remove all doubt.’ I don’t agree, at least not in the context of language learning. I say speak out, remove all doubt, have a laugh about it, and then learn from the experience. Otherwise, how will you ever get any better?

So let’s give Mark Zuckerberg – and every other language learner on the planet – a break.

What did you make of the Facebook boss’s Mandarin? Have you ever surprised people by speaking their language?

Liz

Why learn Chinese Chengyu?

Today’s guest post is by Joe Paterson, a student at Keats School in China. Joe explains Chinese chengyu, which are absolutely fascinating and a perfect example of why we love languages so much – they’re all so unique and interesting. Do any Chinese speakers have more examples – or does the language you’re learning have an equivalent?

Each language has its own idiomatic richness. English is full of proverbs, sayings and odd phrases like ‘Bob’s yer uncle’. Chinese is no exception. When you learn Chinese in China, you will definitely come across all kinds of interesting and creative ways of saying and expressing things. 土包子 (tubaozi/earth steamed-bun) means a country bumpkin or someone with backward or poor taste, and to wear 绿帽子 (lv maozi/ green cap) means to be cuckolded. But perhaps the most uniquely Chinese idioms are 成语 (chengyu).

Each language has its own idiomatic richness. English is full of proverbs, sayings and odd phrases like ‘Bob’s yer uncle’. Chinese is no exception. When you learn Chinese in China, you will definitely come across all kinds of interesting and creative ways of saying and expressing things. 土包子 (tubaozi/earth steamed-bun) means a country bumpkin or someone with backward or poor taste, and to wear 绿帽子 (lv maozi/ green cap) means to be cuckolded. But perhaps the most uniquely Chinese idioms are 成语 (chengyu).

Chengyu are four character phrases that can be thrown into daily conversation but will throw up a wealth of meaning and significance to the interlocutor. Some of these phrases seem quite bizarre without a context, but many have a background story which explains the meaning and also conjures up images that reinforce the word’s meaning.

The first chengyu we will look at is 东施效颦 (Dongshixiaopin/ Dong Shi effect frown). The literal translation is altogether puzzling but a native speaker would instantly know the meaning to be to imitate someone but have the opposite to the desired effect. It is only when we know the background story to the saying that we can fully comprehend it. The story goes that there was a beautiful girl named Xi Shi in the ancient Yue state who was admired by everyone in the village. However Dong Shi, another girl, was ugly and could never command attention. One day when Xi Shi fell ill she walked out of the door holding her hand to her breast, her face contorted in pain. All the villagers were concerned at her trouble and pain. Seeing this, Dong Shi attempted to imitate her mannerism. But when the villagers saw such a grotesque sight they were repulsed and ran away.

Nowadays people might use 东施效颦 to describe someone blindly imitating a pop star’s outfit, only to be ridiculed themselves for looking stupid. Or, someone plagiarising another’s business idea only to find themselves go bankrupt.

The second chengyu is 刻舟求剑 (ke zhou qiu jian/mark boat search sword) which means to pursue a goal despite changing circumstances that should be considered, or, in short, being stubborn in a foolish pursuit.

The phrase comes from a story where a man drops his beloved sword into a river. He marks the side of the boat to show where the sword fell in. Once at the shore he dives back in to find the sword but to no avail. Of course between marking the boat and getting to the shore the boat has moved downstream. An example of when his phrase could be used might be if someone insists in investing in a certain product even if research shows that the product might not sell.

Other phrases are not strictly chengyu but are made up in the same structure and used in daily speech, even though most people may not know the exact origin of the term.

乱七八糟 (luan qi ba zao/confusion seven eight pickle) is a word used to describe anything messy and unorganised, from a bedroom to the way in which someone does something. The phrase actually originates from a late Qing dynasty novel by Zeng Pu, in which he describes the way craftsmen used to keep their workshops in a 乱七八糟 state.

Many common chengyu may not have such an interesting background but serve to colour the language with images that are created by the visual characters themselves or their meaning. 自讨苦吃 (zi tao ku chi/ self ask for bitter eat) provides an image for the idea to ‘ask for trouble’ and 利欲熏心 (li yu xunxin/ profit desire smoke heart) would be the equivalent of the English phrase ‘blinded by greed’, but creates an interesting image of the desire for profit creating a vapour masking the heart.

The ability to use chengyu well is very much admired in China and so it is well worth trying to improve one’s own use and trying to learn more. After a while some chengyu become so natural to explain a certain scenario or situation that sometimes they even surpass one’s own mother tongue equivalent word or phrase. Taking a Chinese language course from a professional language school could help to establish one’s linguistic and cultural foundation to be able to understand and use chengyus in a versatile way.

Joe Paterson (Keats School)

Which language are you learning? The results!

We had a great response to our recent language learning survey; thank you to everyone who took the time to complete it. First things first: we’re delighted to announce that the winner of the iPad mini prize draw is Konstantia Sakellariou. Congratulations, Konstantia – your iPad is on its way!

We wanted also to share a few of our findings with you. Some of the results from the survey were as we expected, others were quite surprising. Here are just a few of the things you had to tell us. Thanks again for all your thoughtful responses, we’ll put them to good use.

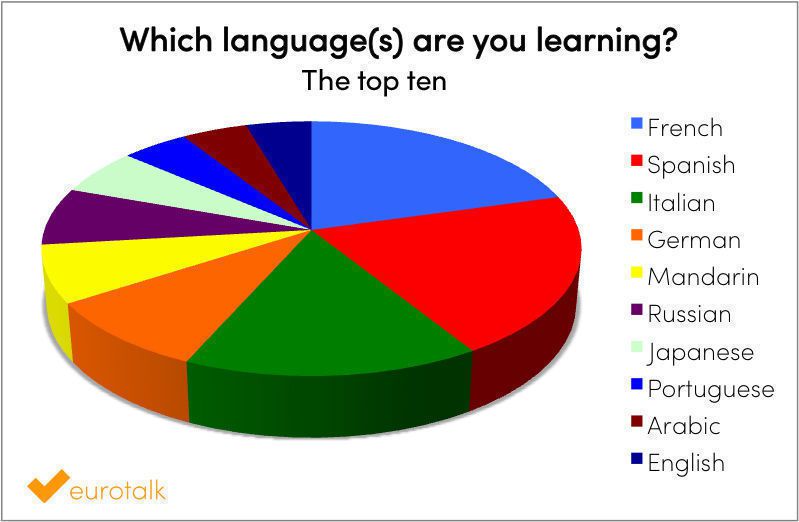

Which language(s) are you learning (or would like to learn)?

The first question was pretty straightforward. A couple of people ticked every language on offer (over 100) – now that’s what we call ambition! – but most chose between 1 and 5. Here are the top ten most popular languages:  Other popular choices included Greek, Swedish, Dutch, Brazilian Portuguese, Norwegian, Irish, Polish and Icelandic. We also got some requests for languages we don’t yet offer, like Guernésiais and Twi – we’ll do our best to add those languages to our list, so watch this space!

Other popular choices included Greek, Swedish, Dutch, Brazilian Portuguese, Norwegian, Irish, Polish and Icelandic. We also got some requests for languages we don’t yet offer, like Guernésiais and Twi – we’ll do our best to add those languages to our list, so watch this space!

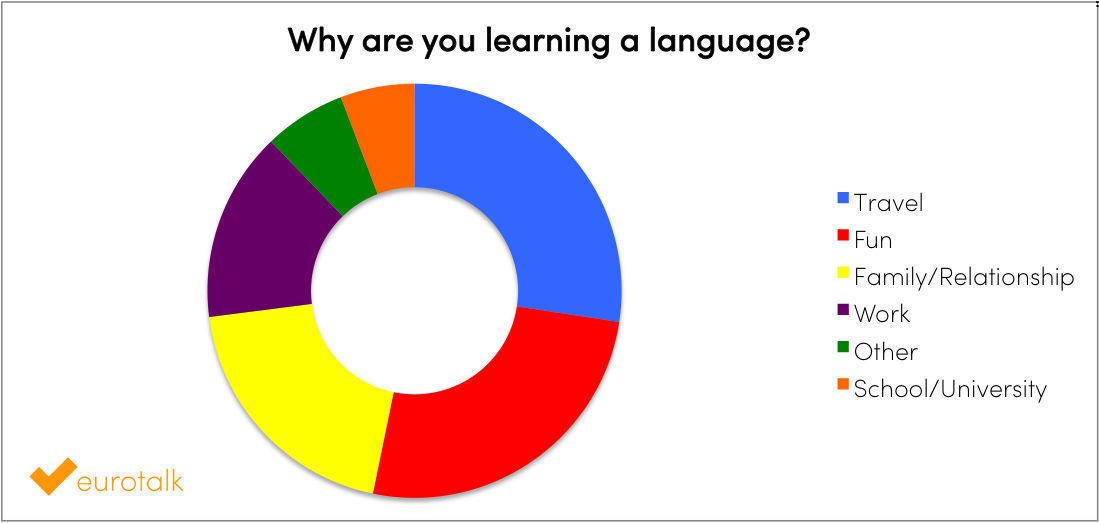

Why are you learning a language?

Next, we wanted to know why you’re learning a language. Nearly half of the respondents chose travel as a reason, and almost as many said they were learning a language just for fun. 36% of respondents said it was for family reasons or for a relationship, and 27% for work. The results were quite evenly split though, showing that there’s no one overwhelming reason – everyone has their own motivation.  Among the other reasons, we had a range of answers, including an interest in the culture of the language, personal challenge and wanting to follow literature, film and music in other languages. Many people are living in another country, which was their main motivation for learning the local language. And one person said that their heart asked for the knowledge, which we loved 🙂

Among the other reasons, we had a range of answers, including an interest in the culture of the language, personal challenge and wanting to follow literature, film and music in other languages. Many people are living in another country, which was their main motivation for learning the local language. And one person said that their heart asked for the knowledge, which we loved 🙂

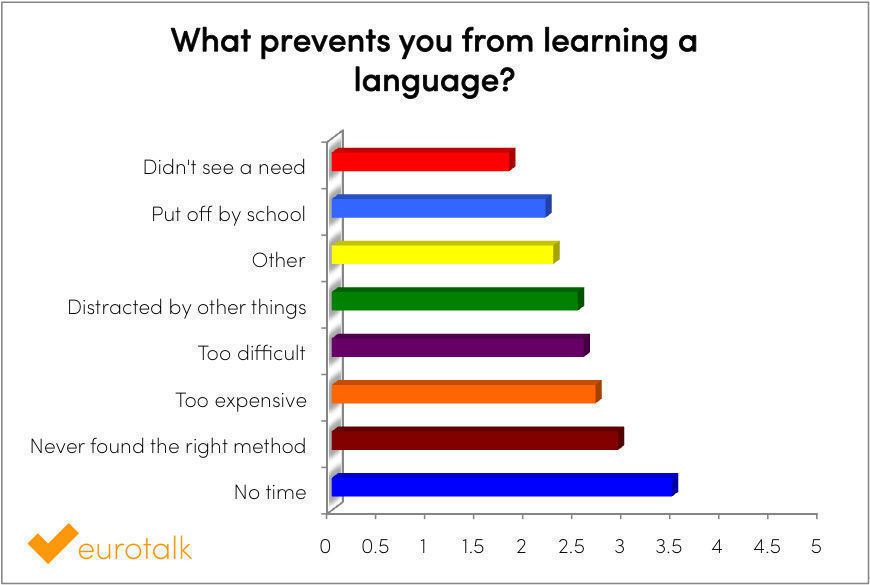

What prevents you from learning a language?

We were also interested to know what stops people from learning a language, so we asked you to rate the following reasons out of 5. The most common barrier to learning is a lack of time, followed by not having found the right method, and then the cost involved.  Incidentally, if you’re facing any of these barriers, you may like to check out our recent posts, on finding time to learn a language and learning on a budget. And if you’re looking for resources, did you know you can try out the EuroTalk learning method for free? Either visit our website, or download our free app, uTalk for iOS, to give it a go. We believe learning a language should be fun, because our research shows we learn much better if we’re enjoying ourselves, and this in turn makes it a lot easier to overcome the obstacles that get in the way. See what you think! Other answers included not having an opportunity to use the language, a lack of motivation and difficulty finding resources for the particular language they wanted to learn (we may be able to help there – we’ve got 136 languages and counting…).

Incidentally, if you’re facing any of these barriers, you may like to check out our recent posts, on finding time to learn a language and learning on a budget. And if you’re looking for resources, did you know you can try out the EuroTalk learning method for free? Either visit our website, or download our free app, uTalk for iOS, to give it a go. We believe learning a language should be fun, because our research shows we learn much better if we’re enjoying ourselves, and this in turn makes it a lot easier to overcome the obstacles that get in the way. See what you think! Other answers included not having an opportunity to use the language, a lack of motivation and difficulty finding resources for the particular language they wanted to learn (we may be able to help there – we’ve got 136 languages and counting…).

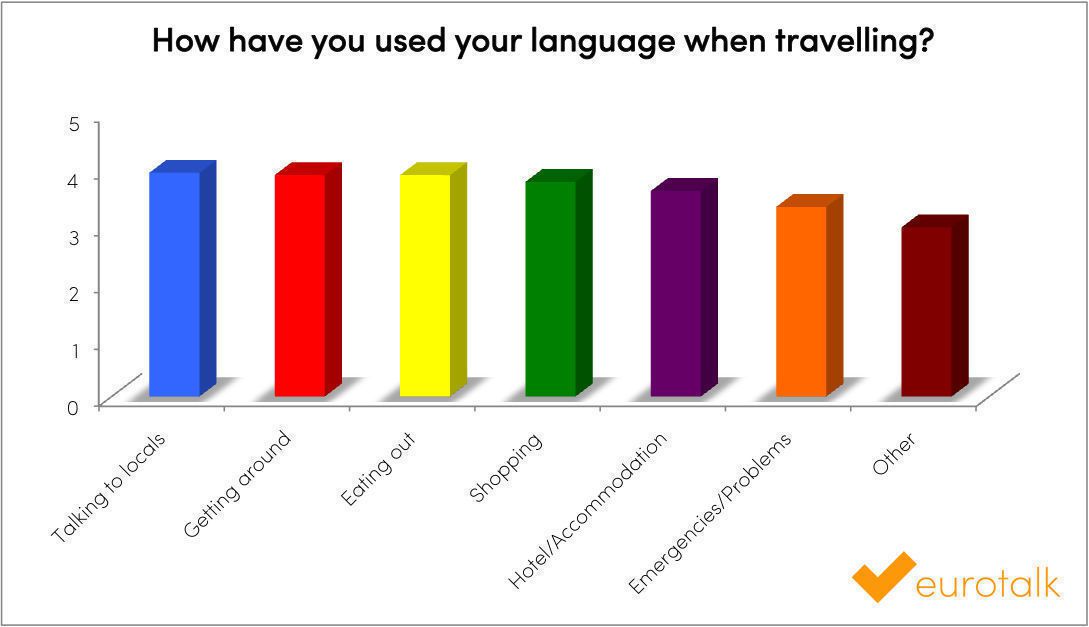

How have you used your language when travelling?

Finally, we asked how knowing another language has been useful when you’re travelling. There was no clear winner here, which just goes to show knowing a language is always useful! But the top response was that it gives you the ability to talk to locals in their own language; many people added that they felt more welcome as a result and that it gave them independence so they could make the most of their trip. There were lots of practical reasons too, with getting around and eating out narrowly beating shopping in the poll. If you missed out on the survey this time, don’t worry – we’re planning another one soon, so keep an eye on the blog (you can subscribe by email above to get the latest updates), or follow us on Facebook or Twitter. And if you didn’t answer this survey but would still like to have your say on any of the questions, you’re very welcome to email us or add your thoughts in the comments below.

If you missed out on the survey this time, don’t worry – we’re planning another one soon, so keep an eye on the blog (you can subscribe by email above to get the latest updates), or follow us on Facebook or Twitter. And if you didn’t answer this survey but would still like to have your say on any of the questions, you’re very welcome to email us or add your thoughts in the comments below.

Liz

Data above based on 877 survey responses.

Translation mistakes – not just for laughs

Today we have a guest post from language company, thebigword, on famous translation mistakes, some of which had serious consequences. Mistakes are common, and to be expected, when you’re learning a language – but when it really matters, it’s important to get it right!

Over the years there have been many translation ‘slip ups’ and faux pas, and whilst the mistakes may seem funny some can have a far more serious impact. Reputable language solution agencies such as thebigword, specialise in international translation and you can bet your bottom dollar that they wouldn’t be caught making slip ups like the following.

There have been many incidences over the years where mis-translation can go from highly amusing to potentially life damaging. For example, Mead Johnson Nutritionals in 2003 had a case raised against them when 4.6 million cans of baby food had to be recalled. The translation error, which was caused by effectively being lazy, meant that the prescribed recipe translated into Spanish could have caused massive health issues, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Businesses and the world financial markets have also paid the price at the hands of poor translation, most notably when the price of the U.S. dollar was sent spiralling after an incorrect translation of an article by Guan Xiangdong for the China News Service. Guan’s original piece was meant to be a speculative overview of a series of financial reports, but instead it was translated in a more aggressive tone, which ultimately made readers in the U.S. think it was an authoritative warning and they should move their money and sell shares.

Businesses and the world financial markets have also paid the price at the hands of poor translation, most notably when the price of the U.S. dollar was sent spiralling after an incorrect translation of an article by Guan Xiangdong for the China News Service. Guan’s original piece was meant to be a speculative overview of a series of financial reports, but instead it was translated in a more aggressive tone, which ultimately made readers in the U.S. think it was an authoritative warning and they should move their money and sell shares.

The Chicago Tribune published a highly shareable article not that long ago when it collated a series of images captured by tourists on their worldly travels. Examples from China included, ‘man toilet’ and ‘The government decides to cracking down fakes intensively for another three years’. However, our favourite has to be, ‘Because there is the situation when a step is bad, please be careful’. We’re pretty positive that was meant to say ‘mind your step’.

Of course, no faux pas goes unnoticed in the world of marketing, where language on billboards or even newspaper advertising isn’t missed by the most ardent observer.

The popular Dairy Association campaign, ‘Got Milk?’, raised an eyebrow or two when in Mexico it was translated to ‘Are you lactating?’ And in France, Colgate produced a new range of toothpaste called Cue; little did anyone realise that it had the same name as a well-known adult magazine. Now that is what we call a faux pas!

Do you have any favourite translation errors? Please share them in the comments below.