10 sport stars who speak other languages

It can often feel like life is all about sport, whether we like it or not. But have you ever wondered how good sports stars are at languages?

It can often feel like life is all about sport, whether we like it or not. But have you ever wondered how good sports stars are at languages?

It turns out, pretty good. Like anyone who has to travel a lot for their work, athletes often find knowing only their native language isn’t enough. Here are 10 great examples of sports stars who speak more than one language.

Gary Lineker

Besides English, the former footballer learnt Spanish while he was playing for Barcelona, and picked up some Japanese when he later moved to Nagoya Grampus Eight. He’s now a passionate ambassador for languages in schools, saying in an interview with TES last year, ‘the learning of languages, for me, will always be helpful for the vast majority at some stage in their life’.

Roger Federer

Not content with winning a frankly quite ridiculous 17 Grand Slam titles, the Swiss tennis player also speaks four languages fluently – his native Swiss German along with French, English and German. He’s known for his ability to switch effortlessly between languages in interviews and press conferences and can quite comfortably answer journalists’ questions in their own language, a feat some of his fellow tennis players can’t keep up with. Wouldn’t be the first time.

Tom Daley

The British diver recently got an A in his Spanish A-level (congrats, Tom!), and makes good use of his language skills when in Mexico, where he spends a lot of his time. Here’s a video of him showing off his Spanish.

Jonny Wilkinson

Here in England, Jonny Wilkinson is known (at least by me) as that guy who’s pretty good at drop goals. But he’s also a bit of a superstar in France, where he’s been playing for Toulon since 2009. He’s now fluent in French and was awarded honorary citizenship of Toulon earlier this week – giving his acceptance speech in the local language, of course.

Fernando Alonso

The Spanish Formula One racing driver speaks an impressive four languages – Spanish, Italian, English and French. And in case that’s not enough, he’s apparently working on Russian too.

Arsene Wenger

The Arsenal manager is well known for his interest in languages, speaking French, English, German, Spanish, Italian and Japanese. Like Gary Lineker, Wenger’s also known as an ambassador for languages, and last year he was voted Britain’s first Public Language Champion by readers of The Guardian. In this video he explains why languages are so important.

Novak Djokovic

Never one to let Roger take all the glory, fellow tennis champion Novak Djokovic speaks five languages – Serbian, English, German, Italian and French. He studied English and German at primary school, and learned Italian when he worked with coach Riccardo Piati. In an interview with Tennis Talk in 2013, he said, ‘We have a saying in our country: The more languages you know, the more is your worth as a person. I like to understand what people are saying wherever I am, at least to pick up a few phrases of those languages.’

Paula Radcliffe

Long-distance runner Paula Radcliffe has a first-class degree from Loughborough University in European Studies, and speaks French and German fluently. She now lives in Monaco with her husband and two children, who are both bilingual, attending a French school but also fluent in English.

Cesc Fabregas

Another Barcelona footballer, Fabregas speaks four languages – Spanish, Catalan, English and French, and his Twitter feed is multilingual. When asked about his language skills in 2005, he replied, ‘These days you have to keep studying, not least because my mum tells me so.’ Words to live by.

Daniela Hantuchova

And finally, another tennis player, because tennis is my favourite. Daniela Hantuchova, from Slovakia, is by all accounts a very talented lady. Besides her tennis career, she’s also a trained classical pianist, and speaks – wait for it – six languages: Slovak, Czech, English and German fluently, and some Croatian and Italian.

Does anyone else feel like a bit of an underachiever now, or is it just me?

If you know any other examples of sports stars who speak other languages, please tell us about them in the comments.

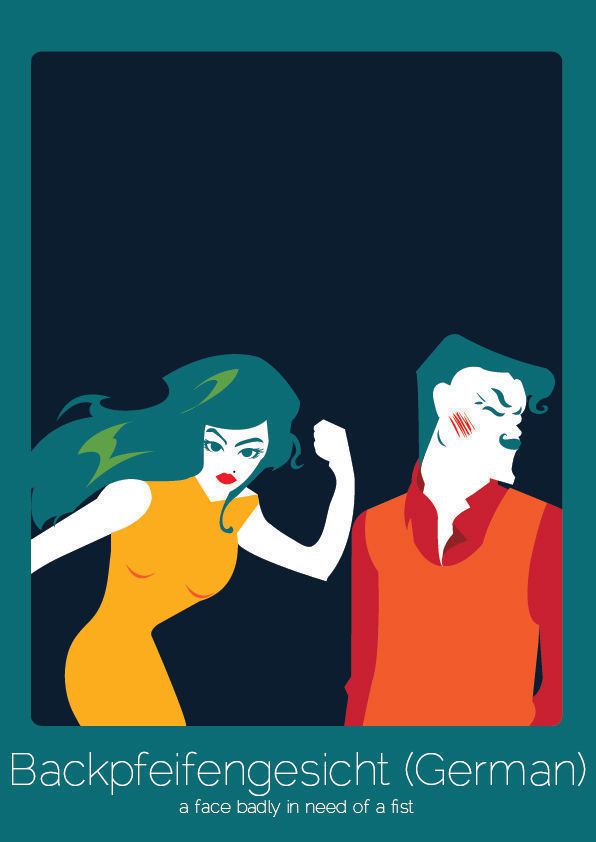

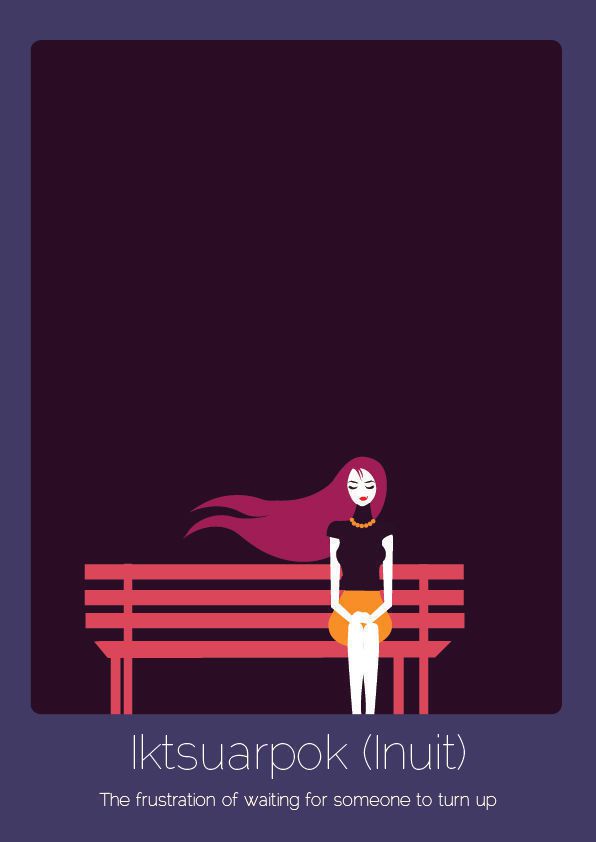

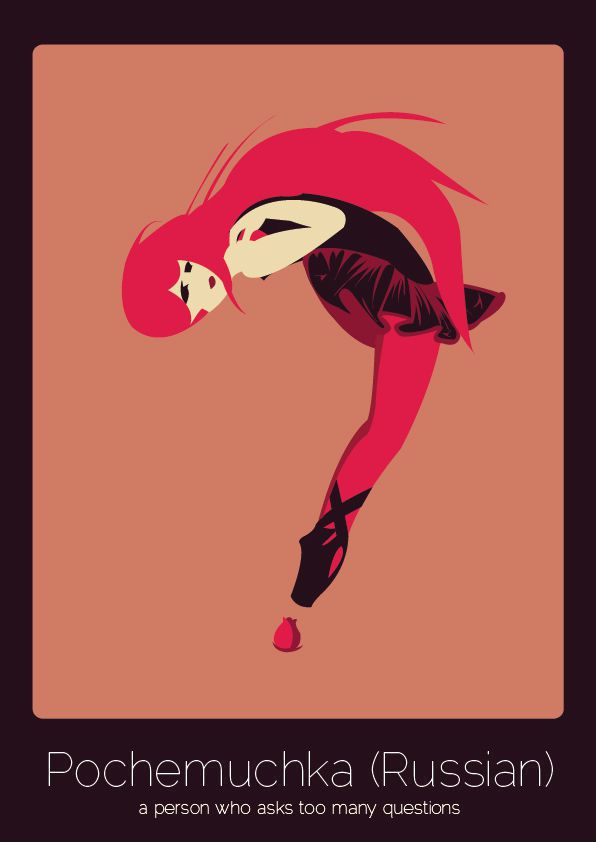

Found in translation – untranslatable words, in pictures

If you liked our recent infographic on words that don’t exist in English, you’ll love this. New Zealand-based designer Anjana Iyer has been working on a project called Found in Translation, illustrating 41 ‘untranslatable’ words so far, with more to come.

We asked Anjana about the background to her project, and where she gets her ideas from. Here’s what she had to say…

What’s the 100 Days Project all about? How did you get involved?

The 100 Days project is basically choosing one creative exercise, and then repeating it every day for 100 days. It was started three years ago by Emma Rogan, who is quite a renowned senior designer in New Zealand. I came across this through one of the creative meetups happening in Auckland every week, and I decided to participate to improve my illustration skills.

What made you choose untranslatable words for your subject?

I wanted my 100 Days project to be something compelling enough to do every single day. I have had a fascination with learning new languages for the longest time and I just happened to come across this article about 14 words with no English equivalent on The Week. I knew I wanted to base my project around illustrations, since I have only been illustrating for the past two years and I still have a very long way to go, and this was a perfect medium to improve my skills.

This project was started last year as a part of the 100 Days project but I had to drop it after Day 41 due to some professional and personal commitments. It’s suddenly been brought to spotlight because of my friend who recommended me to DesignTaxi and it went viral from there. And with the growing response that it’s gotten, I have restarted the series to include more illustrations.

How did you choose which words to illustrate?

Well, when I first came across these words, I could think of one friend or another when it came to certain words. For example, the Yiddish word Shlimazl (which means a chronically unlucky person), reminded me of a classmate who had the worst luck with our professors. And so I picked words which we could all relate to in way or another and maybe share a laugh or two.

Do you have a favourite so far?

Iktsuarpok has a been a favourite word, simply cause it holds so much meaning. It’s waiting, whether you are waiting for the bus to show up or for the love of your life. It perfectly describes that inner anguish. From the point of view of illustration, I am very happy with how Schadenfreude turned out. That was fun to illustrate.

What’s your background as a designer?

I am a media designer with three years of experience. I love illustration and web design in equal measure. I quit engineering to become a designer. When it comes to illustrations, I love doing mostly vector work. Currently I am in the final year of my studies as a web design student.

Do you speak any languages yourself?

Well, being from India, I think we are born to speak several languages. I do speak about five Indian languages and I have a working understanding of French.

Can you give us a sneak preview of any forthcoming illustrations?

It’s quite surprising how some words can really unite people. The Portuguese word Saudade is such a popular one. I have lost count of the number of people who have requested an illustration of said word. And I am looking forward to completing that one.

To see some of her other illustrations, check out Anjana’s website.

Thanks to Anjana for talking to us; we’re looking forward to seeing more of her brilliant work!

Do you have any favourites? Or any words you’d like to see illustrated? Let us know in the comments.

10 reasons to visit… Russia

Today, we’re going to Russia. At least in spirit. Here are my top ten reasons for visiting Russia – and, trust me, it’s been hard narrowing it down to ten!

1. Train Travel

Travelling by train is arguably the best thing you can do in Russia, so try to leap on one as soon as you arrive. Everything about it is an experience, especially if you’re used to the slender commuter trains of the UK. In Russia, trains are absolutely vast, and appear even more so since you have to climb up into them from ground level. They are slow and ponderous, stopping for twenty minutes or so at each station (enough time for you to get out, stretch your legs and if you’re lucky buy a smoked fish from a vendor on the street) and crawling in between.

Inside, a strange etiquette reigns, so that on the plus side you might be invited to share food and drink with your neighbour, and on the minus side you will be obliged to give up your ground level bunk to anyone older than you who only managed to secure a second tier berth. Presiding over the whole show is the train assistant, who will sell you bed linen and glasses to make tea from the great water boiler at the end of the carriage, and as a special bonus will shake you vigorously by the foot to wake you before your stop.

2. Petersburg

The Hermitage, obviously. You could easily spend a day wandering around it, drinking in all the extravagant beauty. In fact all of Petersburg is nice for walking around dreamily, looking into little museums and palaces and drinking coffee on Nevsky Prospekt.

3. Moscow

Tricky condensing this into one paragraph, but I think the best things to do in Moscow are to get the metro (looking at the sumptuously decorated stations along the way) to Sparrow Hills and there look at the view, then go out to the Novodevichy Cemetery where you’ll find various big names, including Shostakovich, Bulgakov and Mayakovsky. This cemetery shows enormous wealth and the desire to show it off after death, so look out for any especially showy tombstones. Then, of course, Red Square and the Kremlin are worth a good long visit, as well as Lenin’s Mausoleum, if you don’t mind being marched past the body at a fair lick and glowered at by armed guards from every corner within.

4. Hospitality

Although Russians often seem to have a reputation for being a bit moody when you first meet them (especially if you meet them on the street or in a public place, where it is a little frowned upon to show excessive emotion), you can very quickly make solid friends for life in Russia. Advice (on clothing, appearance, relationships, career choices) can be offered pretty freely in a way that can be startling, but is generally very well-intentioned. If you’re invited round for dinner, take a bottle or some chocolates, as there will probably be a very generous spread laid on for you.

5. Dachas

If you’re looking for a little bit of peace and quiet, try to get someone to invite you to their Dachas, as this is where Russians traditionally kick back and relax. Out in the country with big allotment-style gardens around them, dachas often are simple buildings with outside toilets and local wells supplying water. People grow vegetables (lots of them), pickle vegetables (often enough to last them through the winter months), make wine and home-brew alcohol, go fishing, hunt for mushrooms, and generally have a great time.

6. All night life

Go out in most cities in Russia and you can stay out all night. All night! And it’s not just clubs that stay open all hours, but cafes and restaurants too, so that you can actually stay in the same building and have an evening meal, go dancing, get breakfast, sit with a paper and carry on right into lunch, if you want to. A lot of places which look like inoffensive coffee houses and restaurants will acquire some dance-floors and professional dancers come evening, meaning you don’t have to venture out into the cold at all if you don’t want to.

7. The banya

Like with the dacha, if you’re after traditional Russian relaxation then go to a banya. A lot of towns will have public ones (often separate bathing days for men and women) but lots of dachas will have their own private ones. Russians like it pretty hot so if you’re not used to it then it might be a bit of a shock to the system. Extreme, humid heat is followed by being doused with bowls of cold water – relief for a few seconds, at least. Beating each other with birch twigs is also standard practice, but can seem like you’re crossing a barrier if you end up engaging in it with your host.

8. Food

Russian food is all interesting and delicious, but what is particularly excellent is snack food, widely available on kiosks on any street corner. Ever had crisps flavoured with caviar or sour cream and dill? Or dried bread croutons, watermelon-flavoured chewing gum and dried salt fish (a traditional beer snack)? In bars and cafes, beer can be accompanied by fried cheese and deep-fried sticks of bread, or long laces of deeply salted, chewy cheese.

Not that all Russian food is snack food – far from it. Porridge in Russia is so varied that you can have porridge made from a different grain every day of the week, and people take pride in making the traditional soups (you’ll probably come across borshch, the beetroot soup shchi, the cabbage soup, and solyanka, the delicious soup with olives) and salads (of which arguably the best are selyodka pod shuboy – herring under potatoes, mayonnaise and grated beetroot – and salat Olivier, know worldwide as Russian Salad).

9. Weather

Being vast, there is a vast range of weather, but the cold winter is something Russia specialises in and there are lots of excitements around it. Fur markets (selling hats and coats in everything from rabbit to mink) spring up and it becomes a squeeze fitting everyone into the trolleybuses with their extra padding of coats, jumpers, thermals. On the lakes, people will bore holes in the ice and go ice fishing, traditionally accompanied by another, fishy soup, uha, into which you pour a shot of vodka just before eating.

10. Queues

Bit of an odd plus to end on, but queuing is a real art in Russia and it’s such an everyday thing that I quite miss it. The best sort of queue is at a train station, where your first big decision is which queue to join. Don’t be fooled into joining the shortest one, as it might be short because the cashier is about to take her hour-long break. A very small understated sign in the window will give the break times so you can estimate how long it will take the queue to move and choose a line based on that. It’s often best to be armed to the teeth with all the information you might possibly need to book a ticket (train number, date, type of carriage, whether or not you want linen) before getting to the front of the queue, as often the attendants don’t have time for dalliers and won’t hesitate to send you to the back of the queue if they see you floundering.

The other thing to remember about a Russian queue is that when you join it it might be quite a bit longer than it looks. This is because Russians will stand in several queues at once, physically in one and then virtually in another by simply telling the last person in it that they are standing behind them. It’s then the responsibility of that person to advertise the virtual person to anyone who comes along afterwards and of the newcomer to ask who is last (can be a bit confusing when the response to this is to point to someone the far side of the room). Depending on which queue reaches the window first, the queuer will either renounce their place in other queues or niftily dash across to reclaim one of their virtual places.

Got any favourite things about the country you’d like to add? We’d love to hear them! And don’t forget to learn a little of the language before you go.

Nat