Icelandic is not like chicken

by Patricia Ochman

My initial reason for taking on Icelandic was pretty pragmatic: I had started riding Icelandic horses and purchased a friendly Icelandic gelding, Léttfeti. I felt that picking up some Icelandic would allow me to get access to a treasure chest of information about my favorite breed and help me better understand my Icelandic best friend.

I took on a uTalk challenge and started learning Icelandic. Since I know Danish, I figured, how hard could it be? I would have this down in 30 days, no problem.

Well, fruits and vegetables were fine… but then it got thorny. Very thorny, very fast. Icelandic, it turns out, is not that similar to Danish. My initial enthusiasm turned into frustration because I thought this was supposed to be easy. Why were there three genders, four declensions, unusual pronunciation, weird words in weird places?

I gave up. It was too complicated, too different. Sorry Léttfeti, we’ll have to stick to English.

Until one day, I remembered that when I was younger, I refused to learn declensions in Polish because English and French (languages I already spoke) had no declensions. That’s when my teacher said, “That’s just the way it is; Polish has declensions and you’re going to have to learn them.” That response later resonated in my head when my Latin teacher made us repeat “rosa, rosam, rosae, …”. That’s just the way it is in Latin, I thought. I learned Polish and I learned Latin and I accepted declensions. I even started thinking that declensions add richness to a language, just like the pluperfect subjunctive tense adds richness to French.

Later on, I learned Finnish and because I had been told that Finnish is unlike any other European language, I just started from scratch, not assuming I would know anything at all. Hyvää päivää, olen Patricia. It went well and I progressed at a satisfying pace. It was unfamiliar and beautiful.

So then, why was I so frustrated with Icelandic? Could it be that my frustration had nothing to do with the language and everything to do with the fact that I was trying to fit a square peg in a round hole? It is certainly a very comforting feeling to think that something that is new to us is similar to something we already know. After all, we are regularly told “try it, it tastes just like chicken”… But doesn’t that just defeat the whole purpose of trying something new? How about “try it, it’s nothing like chicken, it’s totally unique and your mind may just be blown”?

I was trying to make Icelandic seem similar to something I already knew when it really wasn’t, and that’s what hindered my progress. I tried to put myself in the same mindset I had for Finnish and just told myself that this would be different. I’d have to let go of the buoy I was apparently desperately hanging on to and I’d simply have to embrace Icelandic for all its… well, Icelandicness.

I started focusing on the things I already knew in and about Icelandic and built on that. I tried to figure out its internal logic, its particularities, its flow. I started repeating out loud the words and sentences I learned and slowly made sense of them. Eyjafjallajökull is really not that scary when you understand that it’s just a juxtaposition of “islands”, “mountains” and “glacier”. Icelandic started to make sense and I started loving it. I’m still a beginner, but I’m now an excited beginner, unafraid of straying from what I already know. Vel gert!

I believe learning languages expands one’s mind, and this may be a reason why. Learning a new language means getting out of that familiar English, French, German, etc. playpen and discovering new ways of organizing and expressing thoughts. Scary at first, sure, but oh how rewarding.

The Language of Chocolate

Ah chocolate, that little sinful delight that you can pretty much find in every corner of the globe. Eat it, drink it, wear it or even play with it, you simply can’t get away from it. Since it’s National Chocolate Week I was curious to find out where the word ‘chocolate’ actually comes from.

Unfortunately there isn’t really a concrete answer that states its exact origins. Some believe it comes from the Aztec (Nahuatl) word ‘chocolatl‘ which referred to a substance produced from the seeds of the cacau tree. Others believe the Spanish coined it from the Mayan word ‘chocol‘ (hot) and the Aztec word ‘atl‘ (water) when early explorers came across a beverage made from the seeds.

It only goes to show how far back the beginnings of chocolate as we know it are embedded into our history. If you’re looking for interesting ways to use the word chocolate in other languages, here are a few to start you off with.

If you ever come across something or someone that you find utterly useless, then the expression ‘as much use as a chocolate teapot‘ might come in handy. Science has even proven how useless a chocolate teapot really is.

In French, you might use the phrase ‘tablettes de chocolat‘ to refer to a particularly svelte and toned looking man. There are some things about the French language that I just love.

‘Es el chocolate del loro‘ in Spanish literally translates to ‘the parrot’s chocolate’, but is in fact referring to the insignificance of a small amount of money when compared to a much larger amount. I’m still trying to work out where the parrot comes into this, though.

And if you find yourself in a particularly confusing situation that defies all sense of logic and cohesion, don’t hesitate to swap the English idiom ‘it’s all Greek to me’ for the Dutch ‘daar kan ik geen chocola van maken’ which translates to ‘I can’t make chocolate of that’.

Do you know any other chocolate based expressions? Do let us know! I’m sure they’ll be positively delicious…

Safia

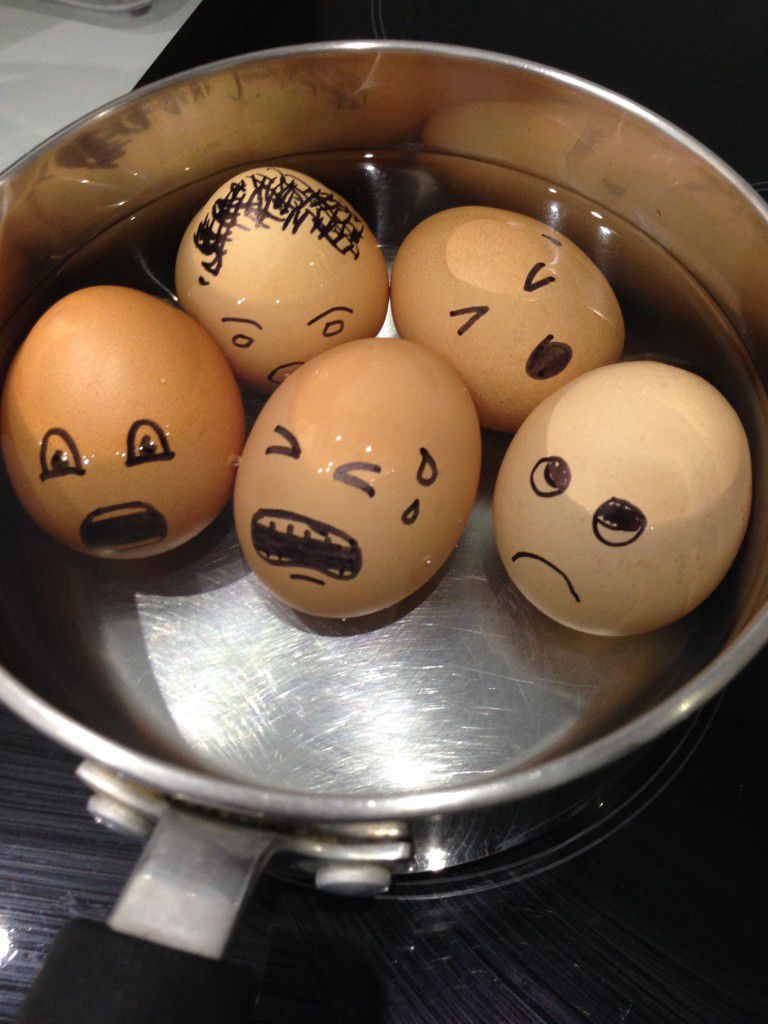

Lost, drowned, in a shirt… how do you like your eggs?

Happy World Egg Day!

English is quite a boring language when it comes to eggs. We boil them, scramble them, poach them, fry them. All very ordinary.

Which is why we were delighted to discover that other languages are more dramatic in their approach to eggs!

Over to Italy:

For Italians, poached eggs are literally ‘eggs in a shirt’ – ‘le uova in camicia’ – possibly because the frilly poached egg white looks like the sleeves of a loose blouse.

Alternatively (but still quite theatrically), you can call them ‘le uova affogate’ (literally ‘drowned eggs’). Poor old eggs!

And now to Germany:

Maybe it’s the same idea of drowning that makes Germans call their poached eggs ‘verlorene Eier’ – ‘lost eggs’. The eggs, like sailors lost at sea, drown quietly in the saucepan.

Or, if it’s a fried egg you’re after, the Germans have a pretty expression for that too: ‘Speigeleier’, literally ‘mirror eggs’. Can anyone tell us why..?

Bullseye!

In Italian, Slovak and Czech (to name but a few), the fried egg is the ‘bullseye egg’- because, of course, it resembles a bullseye (or a porthole, which is the same word): ‘le uova all’occhio di bue’ (Italian), ‘volské oko’ (Slovak), ‘volská oka’ (Czech).

Eyes in a pan?

A similar idea, though slightly more graphic, applies in Bulgarian and Slovenian where the fried eggs (‘яйца на очи’ and ‘jajce na oko’ respectively) translate as ‘eggs eye-style’! So next time you fry an egg, you may choose to remember this vocabulary by imagining a big eyeball staring up at your from the plate… OR you may choose to stick to the safe, if rather boring, English equivalent.

Got any other interesting egg-related vocabulary? Let us know!