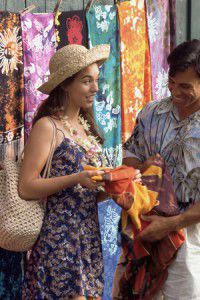

Don’t be shy, get talking!

A recent poll has found that only one in ten British travellers learn any of the language before they visit another country. Some claimed this was because English is now so widely spoken, while others blamed shyness and a fear of saying the wrong thing.

I understand the second excuse much more than the first. Just because we can get away with speaking English doesn’t mean we should. Learning just a few words can make a huge difference, not only to those you’re speaking to but to your own holiday experience. And you don’t have to learn anything complicated. Five per cent of people surveyed said they just learnt the absolute basics, like hello, please, thank you, water and beer. Sometimes all it takes is a friendly greeting in someone’s native language, and they see you in a whole new way – as someone who respects their culture and has made an effort, however small. And that will come across in the way they treat you, making your time in the country a lot more fun. Not only that but you’ll feel pretty good about yourself – I remember several years ago on a school trip to Spain, a friend of mine ordered an ice cream in Spanish. An ice cream – it was as simple as that. But she was so proud of herself when the vendor understood her and she completed the purchase in a language not her own.

Benny Lewis, who’s known as the Irish polyglot, has spent nine years travelling in different countries, learning languages as he goes. Every few months he announces a new challenge, learns some vocabulary and then – he just goes to the country and starts talking. He doesn’t worry about making mistakes or getting his grammar slightly wrong.

Obviously we’re not all as brave as Benny. I’m certainly not. But there does come a point when you have to stop being scared and just take a risk. People are not going to point and laugh if you don’t pronounce something quite right. As a general rule they’ll be so pleased to hear you trying to speak their language that they won’t mind at all, and will probably go out of their way to help you get it right next time.

So let’s be brave! Next time you go on holiday try learning a few basics before you go, and see what a difference it makes…

Liz

An Olympic Challenge

The Olympics are only a couple of weeks away and with estimated viewing figures of over four billion, and visitor numbers expected to boom, it seems the eyes of the world will shortly be focused on London.

The stadium is ready, transport tests are being carried out and athletes are getting in their final hours of training. With 205 countries taking part, and hundreds of different first languages, how do you ensure that Rafa Nadal doesn’t end up walking bemused around the Olympic stadium rather than Wimbledon, and that Usain Bolt knows where to buy chicken nuggets before the 100m final?

The stadium is ready, transport tests are being carried out and athletes are getting in their final hours of training. With 205 countries taking part, and hundreds of different first languages, how do you ensure that Rafa Nadal doesn’t end up walking bemused around the Olympic stadium rather than Wimbledon, and that Usain Bolt knows where to buy chicken nuggets before the 100m final?

Being the largest and one of the most multicultural capitals in Western Europe does have its advantages; with 200 ethnic communities, and more than a third of its population speaking at least two of over 300 languages present within London, the Olympic organizers have spent the last two years recruiting volunteers for a vast array of opportunities to ensure the games are a success.

Adverts were posted stating the huge advantages of having a second language and this has resulted in over 1,000 volunteers being selected to man vital information points in the stadium and at major transport links. With Royalty, Presidents and VIPs arriving from all over the world, and with athletes having to be briefed, debriefed, transported and organised, the games have given language learners a great opportunity to become an integral part of the games itself.

It is no wonder then that when Nelson Mandela was asked his opinion on the games he replied, “I can’t think of a better place than London to hold an event that unites the world.”

Will you be watching the Olympics? Or are you coming to London? Maybe you’re even one of the 1,000 volunteers? We’d love to hear what you think about the games and the city.

Glyn

A feast of languages: Shakespeare as we’ve never seen it before

Last Monday, 23rd April, was the 448th anniversary of the birth of William Shakespeare, and marked the launch of Globe to Globe, a series of Shakespeare’s plays performed over six weeks in 37 different languages at the Globe Theatre on London’s South Bank.

On Monday, Troilus and Cressida was performed in Maori by New Zealand’s Ngakau Toa theatre company. Tonight the audience will watch A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Korean. If that doesn’t appeal, how about The Taming of the Shrew in Urdu, Macbeth in Polish or The Merchant of Venice in Hebrew?

Even though I don’t speak any of those languages, I’m quite tempted to go along. Not only is this probably a once in a lifetime opportunity, but I’m intrigued to see how the plays will translate. Even for a native English speaker, Shakespeare’s language is not always that easy to understand, so is there a possibility that by watching a play and having literally no idea what’s being said, I could just be putting myself in for a couple of hours of mind-numbing boredom?

Even though I don’t speak any of those languages, I’m quite tempted to go along. Not only is this probably a once in a lifetime opportunity, but I’m intrigued to see how the plays will translate. Even for a native English speaker, Shakespeare’s language is not always that easy to understand, so is there a possibility that by watching a play and having literally no idea what’s being said, I could just be putting myself in for a couple of hours of mind-numbing boredom?

Well, possibly, but I suspect not. Just as an opera can still move an audience who doesn’t speak Italian, the point that’s being made with this festival is that Shakespeare’s themes and the emotions he portrays are so universal, they can be shared with an audience almost without words. The Globe website describes it best: ‘Shakespeare is the language which brings us together better than any other, and which reminds us of our almost infinite difference, and of our strange and humbling commonality.’ Perhaps Shakespeare didn’t anticipate that his work would one day be portrayed through a haka (the warrior dance best known outside New Zealand as the pre-match rugby ritual), but does that make it any less valid?

A couple of weeks ago, I watched a fantastic performance of Henry V by the Propeller Theatre Company. A whole scene of the play takes place in French, a language I don’t speak and which I’m pretty sure a lot of people in the theatre didn’t either. And yet – we all reacted in the same way at the same time to what we were seeing. If you’d asked me afterwards to translate every word the character was saying, I wouldn’t be able to. But I can tell you why it was funny.

Whether I could make it through a whole play is another question – but there’s only one way to find out! Now the tough part – which play to go for…? Any suggestions?

Liz

The uncertain nationality of The Artist

On 26th February, The Artist swept the board at the Academy Awards, winning five of the twelve categories it was nominated for. This included Best Picture, Director (Michel Havanavicius) and Actor (Jean Dujardin).

However, something has bothered me since the release of this picture.

It is a film with French actors in the two leading roles, made by a French director and with the support of several French film studios. Yet it is a ‘silent’ film and any dialogue from the characters – audible or otherwise – is in English. So with this in mind, can The Artist count as a foreign language film?

It is a film with French actors in the two leading roles, made by a French director and with the support of several French film studios. Yet it is a ‘silent’ film and any dialogue from the characters – audible or otherwise – is in English. So with this in mind, can The Artist count as a foreign language film?

At first glance, it is easy to assume it cannot. The film features English as the ‘main’ language and the characters appear to speak, albeit muted, English dialogue.

But that’s only to the perspective of English-speaking audiences.

News reports on The Artist’s success at award ceremonies describe it as the most awarded French film in history and, at the 2012 César Awards (their equivalent of the Academy Awards), it won the award for Best Film, yet English-speaking films such as Black Swan and The King’s Speech were seen as foreign language films.

To me, it seems confusing that it can be seen as both an American and French film, but how can you define a film, which can only be surely described as ‘silent’ – a genre that hasn’t been on our screens in over 70 years?

The Artist has been seen as Havanavicius’s homage to silent cinema and as a result, it has revitalised the genre for a new generation. Can silent films make their way in the world, or will language be the key player in a film?

Katie

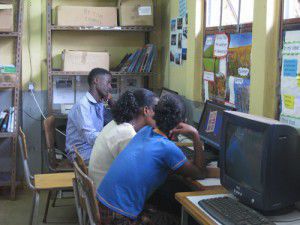

Encouraging English learners in Ethiopia

Our guest post today is by Elizabeth Horsefield, a volunteer with the VSO in Ethiopia.

Ethiopia was perhaps not the intended market for a EuroTalk Interactive Learn English CD-ROM. But it’s going down a storm. I work as a VSO volunteer in a Teacher Training College in a rural area of Western Oromia, Ethiopia. We have an English Language Improvement Centre (ELIC) which recently acquired two new desktop computers complete with headphones and speakers. Perfect.

The students are desperate to improve their English. For most of them this usually involves sitting silently in front of an old copy of some estranged grammar book and making notes. Others even read the Oxford dictionary in the hope that it will one day magically transform their communication skills in English. Many of them went to school in remote areas with very few educational resources. Often their experiences in the ELIC provide a first opportunity to use a keyboard and mouse, so operating an interactive CD-ROM in their second or maybe third language might have been beyond their capacity. It would appear not.

The students are desperate to improve their English. For most of them this usually involves sitting silently in front of an old copy of some estranged grammar book and making notes. Others even read the Oxford dictionary in the hope that it will one day magically transform their communication skills in English. Many of them went to school in remote areas with very few educational resources. Often their experiences in the ELIC provide a first opportunity to use a keyboard and mouse, so operating an interactive CD-ROM in their second or maybe third language might have been beyond their capacity. It would appear not.

Every afternoon (hours scheduled for computer use outside of their regular classes), the students come and learn. Sitting alone or in pairs, I allow them half hour slots to navigate around the different activities and keep score. The cultural context of the material is apparent. These Ethiopian students are not familiar with eating roast chicken, going sailing or playing the trombone. But this only serves to highlight how culture and language are two halves of the same whole and they are quick to overcome any misunderstandings with the help of the pictures and a little guidance from the native speaker (me).

Every afternoon (hours scheduled for computer use outside of their regular classes), the students come and learn. Sitting alone or in pairs, I allow them half hour slots to navigate around the different activities and keep score. The cultural context of the material is apparent. These Ethiopian students are not familiar with eating roast chicken, going sailing or playing the trombone. But this only serves to highlight how culture and language are two halves of the same whole and they are quick to overcome any misunderstandings with the help of the pictures and a little guidance from the native speaker (me).

The local language in the area I live and work is Afan Oromo. I have been making a concerted effort to speak and understand something of this wonderful language with its complex history and rich sense of identity. If only an interactive CD-ROM existed for Afan Oromo, I suspect I would be making nearly as much progress as my students.

Elizabeth Horsefield, Nekemte, Ethiopia