Quote of the week: 5 Sept 2015

“I dwell in possibility.” Emily Dickinson

Embed This Image On Your Site (copy code below):

Talking about Time: Insights from Other Languages

The following post is from Paul, an English teacher who lives in Argentina. Paul writes on behalf of Language Trainers, a language teaching service which offers foreign-language level tests as well as other free language-learning resources on their website. Check out their Facebook page or send an email to paul@languagetrainers.com for more information.

If you love languages, and you’d like to guest blog for EuroTalk, please get in touch; we’d love to hear from you.

Talking about Time: Insights from Other Languages

Time: it’s an essential part of our everyday life, and we talk about it constantly — yet we can’t see or touch it. In English, we usually conceptualize time as a linear distance along a horizontal plane. This seems totally natural to us: time can be long or short, deadlines can be close to us or far away from us, and we have no problem representing minutes and hours on a timeline.

Image via Pexels

But as common as these expressions are, they raise some important questions about how we express time through language. As we’ll see, we often use conflicting metaphors to describe the passage of time. And other languages express time in a completely different way, challenging this anglocentric notion of time that seems so natural to English speakers.

Does time move around us, or do we move through time?

There’s no question that our relationship to time is a dynamic one: days pass, we get older, and the future becomes the past. But who’s doing the moving: time, or us? Expressions like “time flies” or “the hour dragged on” suggest that time moves and takes us with it. Indeed, if we talk about an upcoming test — “The final exam is getting closer” — we can certainly phrase it in terms of time moving towards us.

But we can also talk about the same test by saying “We’re getting closer to the exam date”. Suddenly, the relationship is flipped: now time is static, and we’re moving through time into the future. Indeed, language enables us to conceptualize time in terms as a static entity that we move through, as well as a dynamic entity that moves around us.

In just the English language, we have already found some peculiarities about how we express time. But when we introduce other languages into the equation, the picture gets even more interesting.

Is time horizontal or vertical?

In English, regardless of whether time moves towards us or we move through time, this movement is definitely horizontal. The words we use to describe time — “push back” a deadline, “be ahead” of schedule — are the same ones we use to describe horizontal distances (e.g., “take a step back”, “walk ahead of her”). That is, for English speakers, time is horizontal, with the past behind us and the future in front of us.

But this isn’t necessarily the case in Mandarin Chinese. For Mandarin speakers, it’s possible to talk about time in the same way as English speakers, with time running along a horizontal plane. But it’s also common to use vertical terms to describe the order of events, days, semesters, etc. For instance, the words shàng (up) and xià (down) can be used to express temporal relations: xià ge yuè means “next month”, and shàng ge yuè means “last month”.

Thus, in Mandarin, our familiar horizontal timeline can be flipped vertically, with the past being up and the future being down.

Is time a distance or a quantity?

Two classic ways to express time are the timeline and the hourglass. However, these point to starkly different metaphors. Whereas a timeline suggests that time is a distance, an hourglass suggests that time is a quantity. In English, we generally prefer to talk about time as a distance — saying that something “lasts a long time” is more common than saying it “lasts a lot of time”.

Image via Pixabay

In Spanish, however, this isn’t the case. Indeed, saying tiempo largo (literally “long time”) sounds odd in most dialects; instead, mucho tiempo (“a lot of time”) is much preferred. Greek, too, features this tendency to use volume-oriented metaphors, using words like megalos (“large”) and poli (“much”).

Thus, whereas in English, our use of language favors the timeline, other languages like Spanish and Greek make greater use of the hourglass in their temporal expressions.

Is the past in front of us or behind us?

In English, we can look back into the past and forward into the future. This is as clear as day to us: the past is behind us, and the future is in front of us. Yet in spite of how obvious this may seem to us, this isn’t the case in all languages.

Take Aymara, an Amerindian language spoken in some regions of Bolivia, Peru, and Chile. In Aymara, the past is described as being in front of us, whereas the future is behind us. Though this conception of time seems jarring to us English speakers, it’s logical: we can see in front of us, just as we can remember the past; but we can’t see behind us, just as we can’t predict the future.

To our English-speaking brains, it seems only natural that time is a distance that moves horizontally. But as we’ve seen, this isn’t necessarily the case across languages: time is a complicated concept, and can be expressed through a variety of metaphors. Indeed, as any language learner knows, languages aren’t just sets of words, but rather bring with them a whole new way to view the world. That’s just one of many reasons why learning a language is such a great use of your time — whether that time be above you, below you, in front of you, or behind you.

Quote of the week: 30 Aug 2015

“All our dreams can come true, if we have the courage to pursue them.” Walt Disney

Embed This Image On Your Site (copy code below):

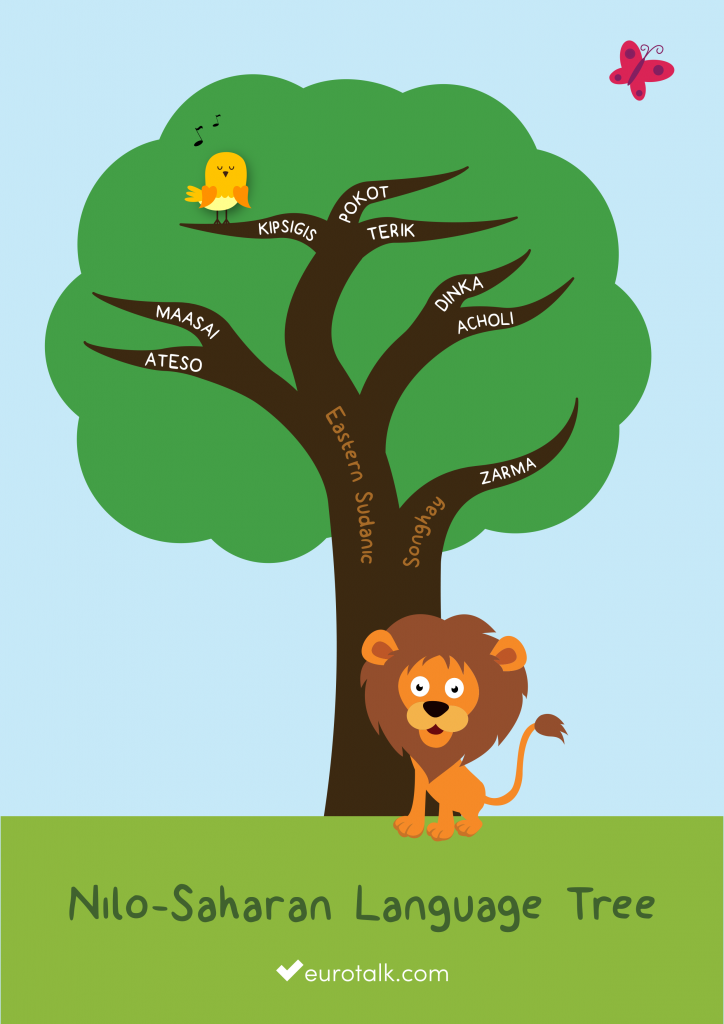

6 language family trees that will make you want to learn them all

We recently shared an illustration showing many of the world’s languages and how they’re all related to each other. And a lot of you really liked it, so we thought we’d give you a closer look at each language family.

With some familiar names and some not quite so familiar, these illustrations show the staggering variety of languages spoken in the world (and this isn’t even all of them!). We’re always fascinated to learn about new or unusual languages, so please do get in touch if you’d like to tell us about yours.

And if you’d like to share any of the images below, please do 🙂

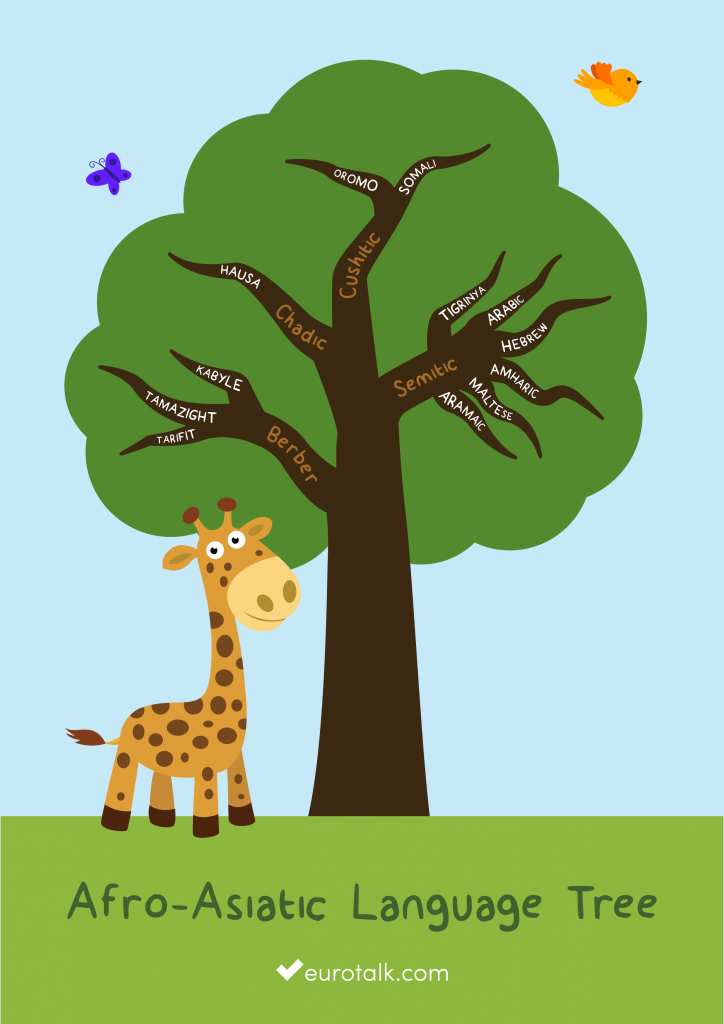

Afro-Asiatic

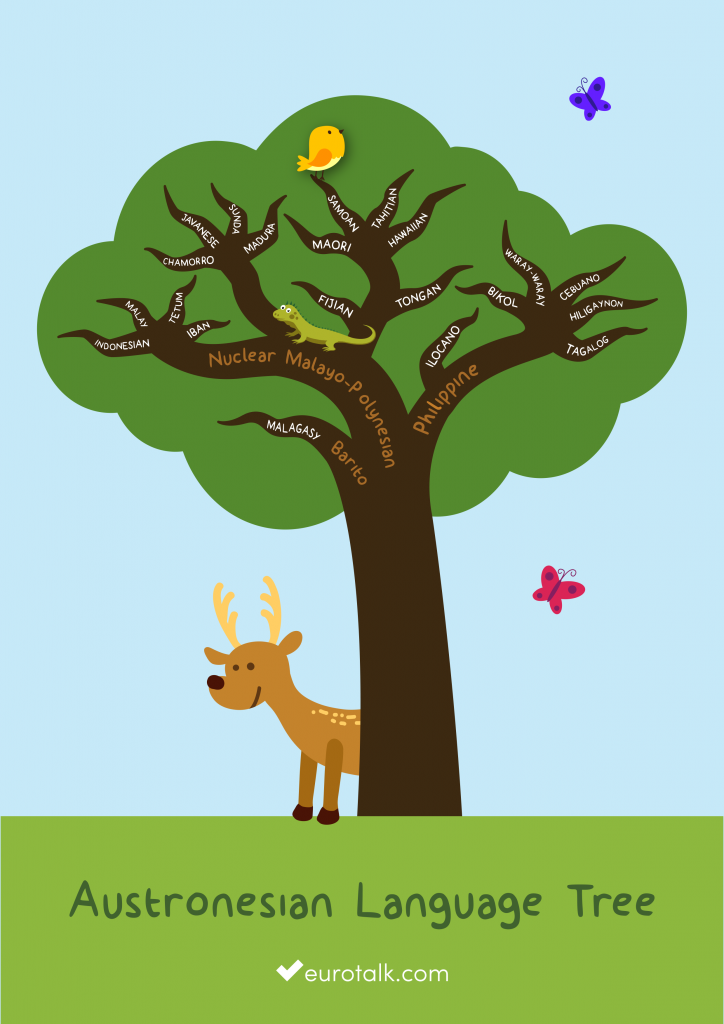

Austronesian

Indo-European

Nilo-Saharan

Sino-Tibetan

Turkic

10 of the strangest festivals from around the world

Today marks the 70th anniversary of La Tomatina, the famous tomato-throwing festival in Buñol, Spain. La Tomatina began in 1945 but didn’t become an official event until twelve years later. Today, about 30,000 people attend the festival, which begins at around 11am on the last Wednesday of August. Traditionally, the tomato fight can only begin when someone has successfully climbed a greasy pole to retrieve the ham that’s been placed at the top.

We love the idea of La Tomatina, because its only goal is for everyone to have a good time. So we had a look at some of the other unusual events that take place around the world each year; here are a few of our favourites. Please feel free to add your own in the comments!

Moose Dropping Festival, Alaska

This festival ended in 2009, sadly, because it got too big for the town of Talkeetna. But it sounds amazing – essentially it involved numbered moose droppings being dropped from a crane onto targets in the town car park; those that landed closest to the centre of a target won prizes for anyone holding a matching ticket.

Wife Carrying Championships, Finland

Nobody seems quite sure how this bizarre festival originated, although it’s believed to have roots in the 19th century practice of wife-stealing. Competitors carry their wife (or sometimes someone else’s wife) across an obstacle course of over 250 metres, with penalties if they drop her, which seems only fair. The races are run by two teams at once, and the winner is the competitor who completes the course in the quickest time – they get to celebrate with their wife’s weight in beer.

Songkran, Thailand

The Songkran festival is a celebration of the Thai New Year in April, and it’s basically a big water fight. People carry water guns and throw buckets of water over each other, along with white talcum powder. The throwing of water is believed to bring good luck and prosperity for the coming year. But watch out if you’re a tourist, as apparently visitors are a particular target for over-excited locals…

Gulal Throwing Festival, India

The Gulal Throwing Festival takes place each March as part of Holi, which is also known as the festival of colours. And it’s easy to see why – the event involves throwing coloured powder (gulal) and water over each other, so everyone ends up covered in a rainbow of colours. As with Songkran, it’s perfectly acceptable to throw gulal at strangers – the event is all very good-humoured and looks like a lot of fun, if incredibly messy.

World Custard Pie Championships, UK

We didn’t even know this existed, but apparently the World Custard Pie Championships take place every June in Coxheath, Kent. Competing in teams of four, participants try to hit their opponents with custard pies, which they’re only allowed to throw with their left hand. They score one point if they hit an arm, three for the chest and six for a pie in the face. The competition, which began in 1967 as a way to raise funds for the village hall, now attracts teams from across the globe, and was won in 2015 by a team from Japan.

Golden Shears, New Zealand

Every March, competitors come together for the world’s biggest sheep shearing event. Founded in Masterton, New Zealand, in the 1960s, the Golden Shears takes place over three days and includes competitions for all levels in shearing and woolhandling. Sheep shearing requires skill, precision and strength, which makes it an unlikely but no less impressive sporting event.

Boryeong Mud Festival, South Korea

This July festival is essentially a celebration of mud, and in particular its cosmetic benefits. Between events like mud wrestling and mud sliding, you can also enjoy mud massages and the World Mud Skincare Exhibition. According to the website, if you don’t have any mud on your body, you get put in ‘prison’ until you do. In addition, visitors can enjoy the beautiful beach setting of Daechon, and there are games and fireworks as part of the festival too.

Tunarama, Australia

Each January, residents of Port Lincoln, Australia, celebrate the town’s biggest industry – tuna. The free festival includes tuna-themed parades and activities for the whole family. Since 1979, though, the highlight has been the World Championship Tuna Toss, which – as you might expect – involves throwing a tuna as far as you can. This year, the winners were husband and wife Matt and Shanell Staunton from Port Lincoln, who won the men’s and women’s individual events with throws of 24m and 11m respectively.

Hadaka Matsuri (Naked Festival), Japan

One just for the men, which features thousands of nearly-naked participants in a crazy night-time dash across Okayama in Japan. The idea is to catch a pair of sacred sticks (shingi) that have been thrown into the crowd by a priest. It can get a little frantic as the men fight to be first to get hold of the shingi, and competitors are asked to include a slip of paper tucked into their loincloth bearing their name, blood type and emergency contact number, just in case.

Harbin Ice Festival, China

The Harbin Ice Festival takes place in Heilongjiang, in the north-east of China every January, and looks really quite stunning. Participants build life-size buildings and sculptures out of snow and ice, which are then lit up in different colours to create a beautiful ice city. In previous years, the art work has included everything from a fully functional slide to a model of the Sphinx. The festival lasts for a month, but the sculptures can stay up longer, if weather permits.

Have you been to any of these festivals? We’d love to hear about your experience!