The Jungle Book’s taught you some Hindi without you realising…

The majority of us have seen The Jungle Book or at least can hum along to ‘The Bare Necessities’. And we are super excited about the release of the new Jungle Book adaptation, so we thought we would find out how Rudyard Kipling came up with all of the animals’ names.

As the film is set in India, many of the names are based on the Hindi translation of the animal themselves. For example ‘Baloo’ is based on the Hindi word Bhãlū which means bear. Bears represented the idea of protection, courage and physical strength. The bear showed authority and was seen as a good omen and arguably Baloo is Mowgli’s main carer. Similarly, Bagheera is almost the same word as Baghirā which means black Indian leopard. This is the same with Hathi, which is the exact word for elephant in Hindi.

Kipling also used influences from Persian and Arabic, with the tiger’s name ‘Shere Khan’. The word for tiger in Persian is just ‘Shere’ which is followed by the Arabic word for lord ‘Khan’. Kipling surrounded Mowgli with animals that all represented strong and powerful companions. All of the animals that looked after Mowgli were given characteristics, which made them ideal for looking after the young boy.

Despite this, the main characte, Mowgli’s name hasn’t come from Hindi or any other Indian language. At times he is named ‘the frog’ due to his lack of ‘fur’ and inability to sit still, or ‘man cub’ by the wolves that raise him, but his name doesn’t actually translate into anything; Rudyard Kipling made it up. Kipling also stated that Mowgli is meant to be pronounced, mow-gli, with the ‘mow’ rhyming with ‘cow’.

The influence of Hindi and other Indian languages in The Jungle Book comes from Kipling’s upbringing in India. He was born there before moving to England to be educated when he was 5, and once he’d completed his education he returned to India. The book is based on the Indian jungle ‘Seonee’ (now known as seoni) however, he had never actually visited this place. Kipling actually used stories from his friends to set the scene of the jungle. Maybe his friends told him about the singing bear in the jungle…

Disney’s Frozen – how to find a voice that fits

‘How are we going to do that in 41 languages?’

This was the question that Rick Dempsey, senior vice president of Creative Disney Characters Voices International, asked himself when he first heard the ice queen’s song in the new Disney movie Frozen.

Dempsey has the incredibly interesting (if you’re a language geek, like me) job of finding foreign language voice artists for the localised international versions of the movie. As the market for films, TV shows and games has become ever more global, companies like Disney are having to move fast in producing translated versions of their films. No simple task, considering the entire film must not only be translated, but also adapted to the culture of another country.

And, especially with a Disney film, the voices are incredibly important. Idina Menzel, who sings the original English-language songs, has a powerful, rich and warm voice. Part of Dempsey’s job is to find a singer with similar qualities to the actor’s voice in each country. Not only that, but the translations of the songs must be tailored as closely as possible to the animation. If you ever watch dubbed movies in another language you speak, you may notice that what the voice artists are saying doesn’t match up with the English subtitles… This is because subtitlers often have to change, adapt and tailor the language to match up with the actors’ (or animations’) lip movements, body language and what’s on screen at the time.

Watching the multilingual version of ‘Let it Go’, you can see how fantastically both the voices and the words have been matched up with the original animation, and how the singers have been picked to match the character and to sound as similar as possible to the English voice.

Nat and I often have the similar (but on a much smaller scale!) task of picking foreign voice artists for our apps, including Maths and uTalk. Picking someone for the task isn’t a simple matter of whose voice sounds good – although this is important! We also have to check that each voiceover artist’s accent is appropriate for the target country (i.e. not a regional accent, or that they don’t pronounce any words in a non-native or non-RP way), that the voice sounds natural and native to a speaker of the language (some people who have been in the UK for a long time may have slightly lost their native accent), and that the voice suits the product. For Maths, we look for warm, friendly and young voices with plenty of enthusiasm. For uTalk, clear pronounciation and a neutral accent are most important.

So, I’m definitely keeping my eye out for a job with Disney on localising their next movie!

Alex

London – a magic city

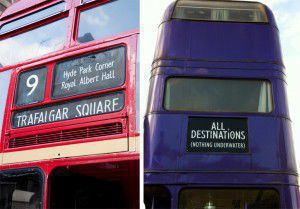

Now I have lived for more than two months in London. And one thing that struck me, is that I see little objects from the Harry Potter movies. I think it makes a difference if you live in England and see the movie, or you live in Germany, like me.

In Germany we don’t have double-decker buses and in one scene, there is a double-decker bus that changes its width. The first time I saw a double-decker bus driving in the city, I remembered this scene. The bus driver in Harry Potter was crazy (drove against the traffic!) and drove very fast through the streets. I know it’s only a movie, but… So I was thinking: “Should I get in? I need this bus, because it will take me to my language school. It is only a bus!” I had no choice but to take a deep breath and get on with it. The bus drove off and thank god, nothing special happened.

I see the architecture in London too. Some areas are similar to the area where Harry Potter lived with his adoptive parents, the Dursleys. I sometimes have the feeling that I have dipped into a different world when I walk around.

Also a typical accessory is the umbrella! As an Englander you need it, because you don’t know when it will start to rain. It is every day a new surprise. And Hagrid, one of the characters, uses it to get in the magic world where the magicians live. He taps the bricks and suddenly the wall opens like a door. Most people always have a umbrella here. Then there is the questions from the perspective of a German, are the people with an umbrella maybe magician? Is the story of Harry Potter true?

Sometimes when I go home, I see lots of people running, running, running! I think, why they always so hectic? They can take the next train. Or? But now I have the answer why! Because they don’t take the train. That is too boring for people here and that do only ‘normal’ people. Here in London you are running, because they do it like Harry Potter and all the other magicians! I think in London everywhere are distributed lots of similar platforms like the platform 9 ¾ at the Kings Cross Station. And instead of catching the Hogwarts Express, they catch the Home Express! Yes, I am sure that is the answer!

Also, when I saw the first time all the children with the beautiful school uniform (in Germany we don’t have uniform) that reminds me of the movie. Everyone here has a different logo from the school they go to. It is like the four houses in Harry Potter: Gryffindor, Hufflepuff, Ravenclaw and Slytherin. And after the school they get out their Nimbus 2000 and start searching for the Golden Snitch? Yes, here in London nothing can surprise me any more! They all look like little magicians! I thought, Lorena, you are in a magic city.

Lorena

The Trouble with the Title

Today’s post is by our Italian intern, Ambra Calvi, a film fan who’s noticed some interesting translations of movie titles…

One of the main pleasures of learning a new language is getting to that point when you are able to watch a film in that language, and you start to understand bits and pieces. Nowadays, it’s become fairly easy to get hold of foreign titles. In the UK in particular, the range of titles available is very diverse, sustained by a long standing interest in so-called “world cinema”. On top of the usual foreign Oscar contenders every year, you can also catch the latest works of an upcoming Turkish director, or challenge yourself with a Thai action film, or spend the afternoon with a gripping Argentine drama.

However, when a film is made available to international audiences outside the nation where it was made, it has to go through an essential process: the translation of its title. This is just one part of the bigger process of localisation which involves translating and adapting all the dialogues for subtitling or dubbing, but it’s an essential part. The title is the film’s immediate presentation, its way of attracting viewers, giving them a hint of the story and instiling some expectations about the experience they are going to have. Together with the poster, those few words can be crucial for the success of the film.

However, when a film is made available to international audiences outside the nation where it was made, it has to go through an essential process: the translation of its title. This is just one part of the bigger process of localisation which involves translating and adapting all the dialogues for subtitling or dubbing, but it’s an essential part. The title is the film’s immediate presentation, its way of attracting viewers, giving them a hint of the story and instiling some expectations about the experience they are going to have. Together with the poster, those few words can be crucial for the success of the film.

Growing up in Italy and being a film buff from a very early age, this is an issue that I’ve had to deal with quite a few times. At weekends, when choosing which film to watch from the leaflet of my local multiplex, if I didn’t know some films I would naively rely on the way their titles sounded. Unfortunately, this wasn’t always a good idea. I soon realised that somewhere in the mysterious places where the films were prepared for the Italian market, some people were using their creative flair to catastrophic results.

I’ll give you some examples: have you ever seen Crystal Trap? Doesn’t ring a bell? That’s because it’s the title under which Die Hard was released in Italy in the Eighties (as “Trappola di cristallo”). What about The Fleeting Moment? No? Well, that was Dead Poets Society (“L’attimo fuggente”). More recently, you could have seen posters of Bitter Paradise (“Paradiso amaro”), and had it not been for George Clooney sitting on a Hawaiian beach you would have never recognised The Descendants.

After keeping an eye on this worrying trend in the past years, I can now group these frequent translation oddities in recurrent categories:

- Radical changes from the original title, often resulting in a more banal – or just silly – new one: see for example How to Lose Friends and Alienate People, translated as Star System: If You’re Not There You Don’t Exist (“Se non ci sei non esisti”). Even worse, The Back-up Plan, which became Nice to Meet You, I’m a Bit Pregnant (“Piacere, sono un po’ incinta”). Similarly, The Break Up was translated as I Hate You, I Dump You, I… (“Ti odio, ti lascio, ti…”). Sometimes the changes of meaning in the title are completely unnecessary: can anyone explain to me why Beasts of the Southern Wild had to become King of the Wild Land (“Re della terra selvaggia”)?

- An unexplainable tendency to romanticize: the popular The Shawshank Redemption became The Wings of Freedom (“Le ali della libertà”), and The Place Beyond the Pines, the new Ryan Gosling film, will be released as Like a Thunder (“Come un tuono”). More specifically, there seems to be a belief that inserting the word “love” in a title will magically attract millions of people craving for super sentimental stories: following this theory, The Time Traveler’s Wife was translated as A Sudden Love (“Un amore all’improvviso”), and the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line became When Love Burns the Soul (“Quando l’amore brucia l’anima”).

- The real horror happens when translators come up with one bad title, and in the years to come they use a series of variations for other non-related films. This happened with Runaway Bride, with Julia Roberts and Richard Gere, which was translated as If You Run Away I’ll Marry You (“Se scappi ti sposo”), and was then followed by Intolerable Cruelty becoming First I’ll Marry You Then I’ll Ruin You (“Prima ti sposo poi ti rovino). Then the lowest point in this disaster: the dreamy, wonderful Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind was smuggled as If You Leave Me I’ll Erase You (“Se mi lasci ti cancello”), alienating the sympathies of most sensible viewers. A similar fashion started with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre becoming Don’t Open That Door (“Non aprite quella porta”), which generated Don’t Enter that School (“Non entrate in quella scuola”, originally Prom Night) and Don’t Open That Closet (“Non aprite quell’armadio”, which was Monster in the Closet).

There are – unfortunately – hundreds of other examples, but this is enough to show how a bad title translation can completely alter the destiny of a film, consigning some masterpieces to oblivion only because they are mistaken for something completely different, or because they sound like cheap b-movies. While in some cases of films with short, simple titles, keeping the original version can be the best solution, generally speaking Italian distributors should really make an effort and try to come up with creative, honest ideas to maintain the intention of the director. After all, Italy has a great tradition in literary translation, so I don’t see why we shouldn’t do our best when it comes to films as well.

There are – unfortunately – hundreds of other examples, but this is enough to show how a bad title translation can completely alter the destiny of a film, consigning some masterpieces to oblivion only because they are mistaken for something completely different, or because they sound like cheap b-movies. While in some cases of films with short, simple titles, keeping the original version can be the best solution, generally speaking Italian distributors should really make an effort and try to come up with creative, honest ideas to maintain the intention of the director. After all, Italy has a great tradition in literary translation, so I don’t see why we shouldn’t do our best when it comes to films as well.

If anyone has any other examples of strange film title translations, we’d love to hear them!

Ambra

The uncertain nationality of The Artist

On 26th February, The Artist swept the board at the Academy Awards, winning five of the twelve categories it was nominated for. This included Best Picture, Director (Michel Havanavicius) and Actor (Jean Dujardin).

However, something has bothered me since the release of this picture.

It is a film with French actors in the two leading roles, made by a French director and with the support of several French film studios. Yet it is a ‘silent’ film and any dialogue from the characters – audible or otherwise – is in English. So with this in mind, can The Artist count as a foreign language film?

It is a film with French actors in the two leading roles, made by a French director and with the support of several French film studios. Yet it is a ‘silent’ film and any dialogue from the characters – audible or otherwise – is in English. So with this in mind, can The Artist count as a foreign language film?

At first glance, it is easy to assume it cannot. The film features English as the ‘main’ language and the characters appear to speak, albeit muted, English dialogue.

But that’s only to the perspective of English-speaking audiences.

News reports on The Artist’s success at award ceremonies describe it as the most awarded French film in history and, at the 2012 César Awards (their equivalent of the Academy Awards), it won the award for Best Film, yet English-speaking films such as Black Swan and The King’s Speech were seen as foreign language films.

To me, it seems confusing that it can be seen as both an American and French film, but how can you define a film, which can only be surely described as ‘silent’ – a genre that hasn’t been on our screens in over 70 years?

The Artist has been seen as Havanavicius’s homage to silent cinema and as a result, it has revitalised the genre for a new generation. Can silent films make their way in the world, or will language be the key player in a film?

Katie