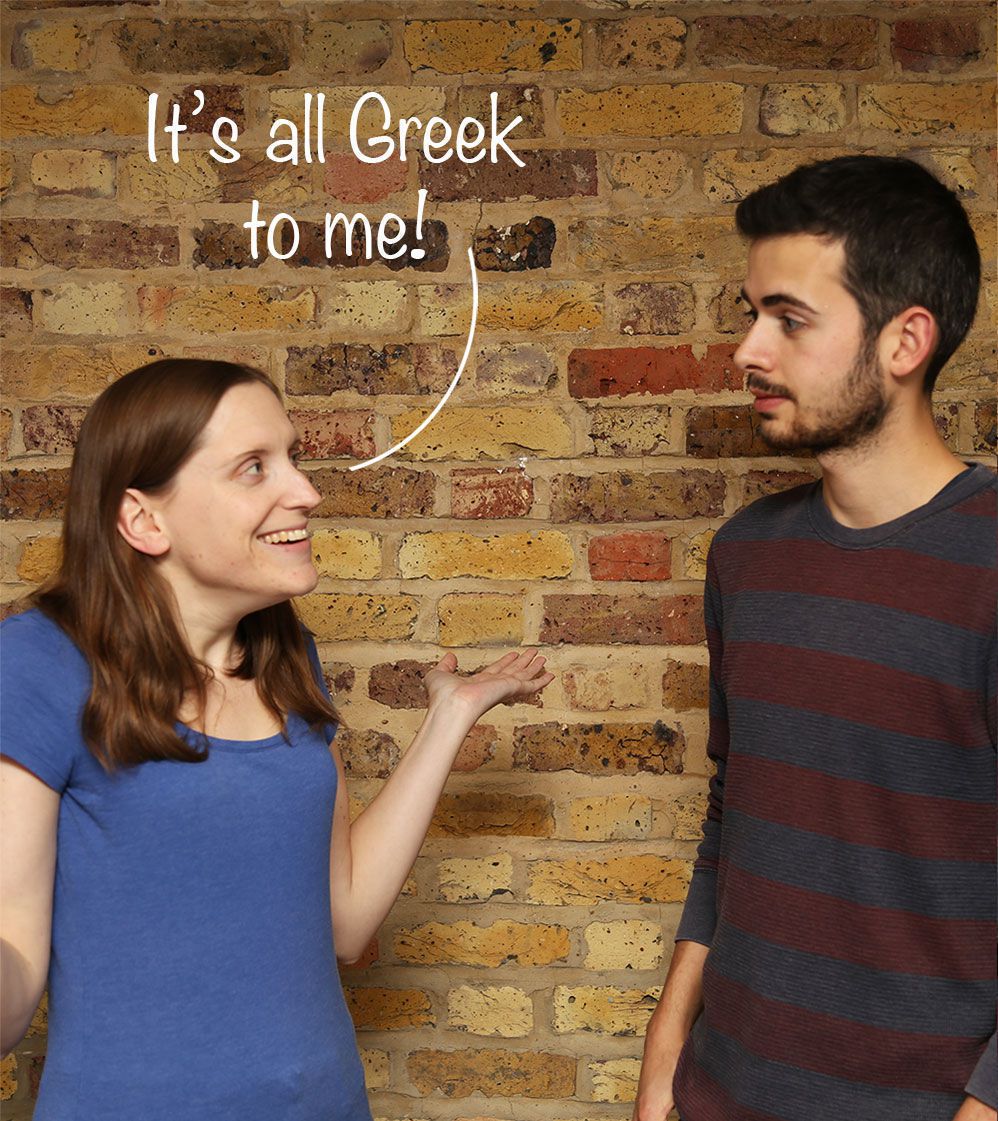

How does a Greek person say ‘it’s all Greek to me’?

‘It’s all Greek to me’. This is what an English speaker might say when they don’t understand something at all. In this context the Greek language is used as a metaphor for ‘something incomprehensible’.

So that got us thinking here at EuroTalk… if an English speaker uses Greek, what does a Greek speaking person use? And in fact how does this expression translate in other languages?

Well as it turns out there is a (somewhat complicated sounding) term for this – ‘language of stereotypical incomprehensibility’. So Greek is the language of stereotypical incomprehensibility in English.

Other languages have similar expressions and they usually pick as a metaphor for ‘impossible to understand’ a foreign language with an unfamiliar alphabet or writing system.

To answer our original question: in Greek the language used as a metaphor for incomprehensibility is Chinese.

Chinese actually turns out to be the most popular choice as a synonym for ‘I do not understand’ and is used in many languages, including Albanian, Arabic, Bulgarian, Catalan, Dutch, Estonian, French, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Spanish, Ukrainian.

Greek itself follows closely, and is used as a language of stereotypical incomprehensibility in: English, Afrikaans, Norwegian, Portuguese, Swedish, Spanish, Polish, Persian.

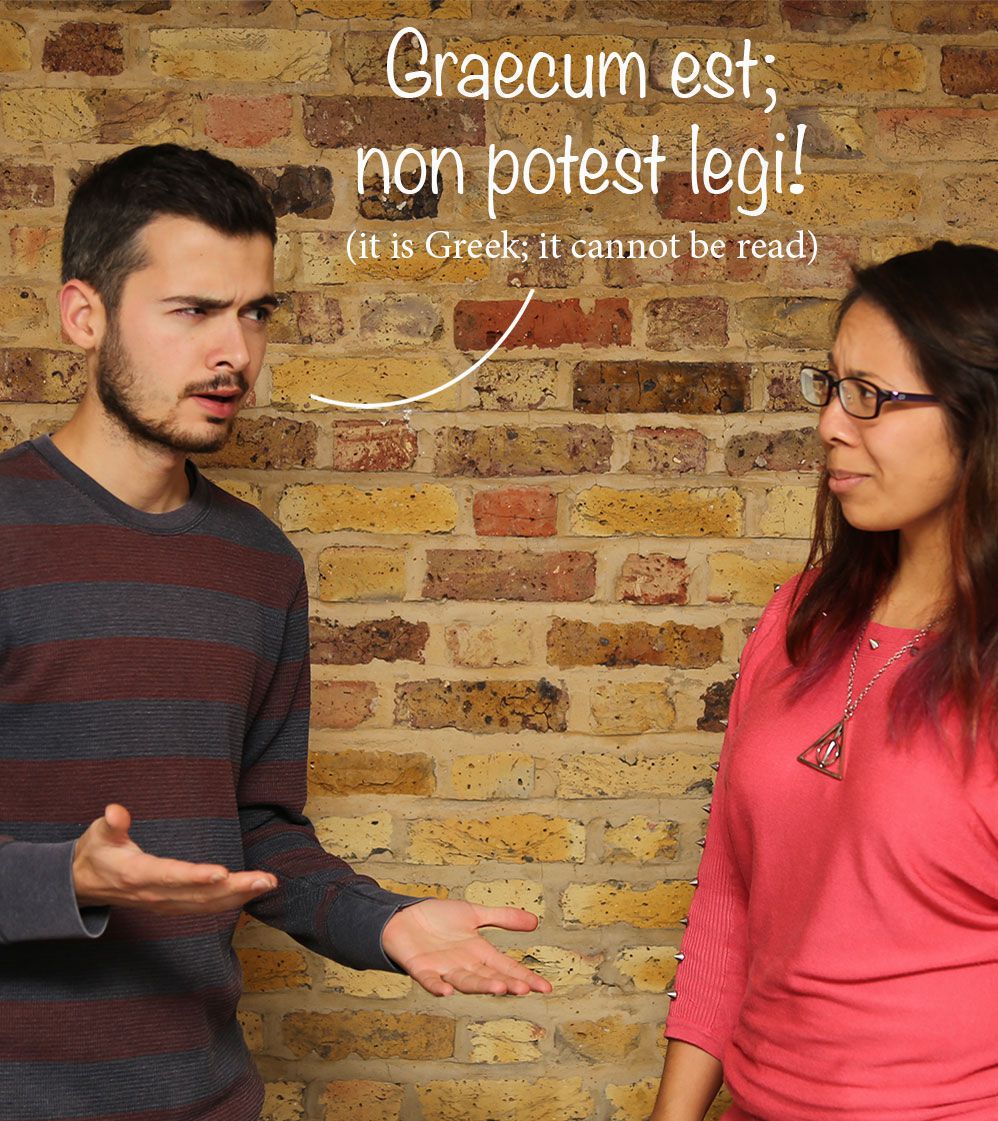

(Bonus fact: the origin of the phrase in some European languages can be traced to the Medieval Latin proverb, ‘Graecum est; non potest legi’, which translates to ‘It is Greek; it cannot be read.’)

Sometimes the language of incomprehensibility is not a specific human language at all. For example a Chinese (Mandarin) speaker would use something that translates roughly to ‘Ghost’s script’, ‘Heavenly Script’ or ‘Sounds of the Birds’. And a Cantonese speaker might say, ‘These are chicken intestines.’

And how about a constructed international language, such as Esperanto? As a tongue-in-cheek reference, an Esperanto speaker would say ‘That’s a Volapük thing’, Volapük being another constructed language (with about 20 speakers).

How about you? What language do you use to mean ‘incomprehensible’? And is your language used by any other languages as a synonym for ‘impossible to understand’?

Bonus points question:

What does a person whose mother tongue is Greek, but who also speaks English, say in English when they want to say ‘It’s all Greek to me’?

Nikolay

Talking about Time: Insights from Other Languages

The following post is from Paul, an English teacher who lives in Argentina. Paul writes on behalf of Language Trainers, a language teaching service which offers foreign-language level tests as well as other free language-learning resources on their website. Check out their Facebook page or send an email to paul@languagetrainers.com for more information.

If you love languages, and you’d like to guest blog for EuroTalk, please get in touch; we’d love to hear from you.

Talking about Time: Insights from Other Languages

Time: it’s an essential part of our everyday life, and we talk about it constantly — yet we can’t see or touch it. In English, we usually conceptualize time as a linear distance along a horizontal plane. This seems totally natural to us: time can be long or short, deadlines can be close to us or far away from us, and we have no problem representing minutes and hours on a timeline.

Image via Pexels

But as common as these expressions are, they raise some important questions about how we express time through language. As we’ll see, we often use conflicting metaphors to describe the passage of time. And other languages express time in a completely different way, challenging this anglocentric notion of time that seems so natural to English speakers.

Does time move around us, or do we move through time?

There’s no question that our relationship to time is a dynamic one: days pass, we get older, and the future becomes the past. But who’s doing the moving: time, or us? Expressions like “time flies” or “the hour dragged on” suggest that time moves and takes us with it. Indeed, if we talk about an upcoming test — “The final exam is getting closer” — we can certainly phrase it in terms of time moving towards us.

But we can also talk about the same test by saying “We’re getting closer to the exam date”. Suddenly, the relationship is flipped: now time is static, and we’re moving through time into the future. Indeed, language enables us to conceptualize time in terms as a static entity that we move through, as well as a dynamic entity that moves around us.

In just the English language, we have already found some peculiarities about how we express time. But when we introduce other languages into the equation, the picture gets even more interesting.

Is time horizontal or vertical?

In English, regardless of whether time moves towards us or we move through time, this movement is definitely horizontal. The words we use to describe time — “push back” a deadline, “be ahead” of schedule — are the same ones we use to describe horizontal distances (e.g., “take a step back”, “walk ahead of her”). That is, for English speakers, time is horizontal, with the past behind us and the future in front of us.

But this isn’t necessarily the case in Mandarin Chinese. For Mandarin speakers, it’s possible to talk about time in the same way as English speakers, with time running along a horizontal plane. But it’s also common to use vertical terms to describe the order of events, days, semesters, etc. For instance, the words shàng (up) and xià (down) can be used to express temporal relations: xià ge yuè means “next month”, and shàng ge yuè means “last month”.

Thus, in Mandarin, our familiar horizontal timeline can be flipped vertically, with the past being up and the future being down.

Is time a distance or a quantity?

Two classic ways to express time are the timeline and the hourglass. However, these point to starkly different metaphors. Whereas a timeline suggests that time is a distance, an hourglass suggests that time is a quantity. In English, we generally prefer to talk about time as a distance — saying that something “lasts a long time” is more common than saying it “lasts a lot of time”.

Image via Pixabay

In Spanish, however, this isn’t the case. Indeed, saying tiempo largo (literally “long time”) sounds odd in most dialects; instead, mucho tiempo (“a lot of time”) is much preferred. Greek, too, features this tendency to use volume-oriented metaphors, using words like megalos (“large”) and poli (“much”).

Thus, whereas in English, our use of language favors the timeline, other languages like Spanish and Greek make greater use of the hourglass in their temporal expressions.

Is the past in front of us or behind us?

In English, we can look back into the past and forward into the future. This is as clear as day to us: the past is behind us, and the future is in front of us. Yet in spite of how obvious this may seem to us, this isn’t the case in all languages.

Take Aymara, an Amerindian language spoken in some regions of Bolivia, Peru, and Chile. In Aymara, the past is described as being in front of us, whereas the future is behind us. Though this conception of time seems jarring to us English speakers, it’s logical: we can see in front of us, just as we can remember the past; but we can’t see behind us, just as we can’t predict the future.

To our English-speaking brains, it seems only natural that time is a distance that moves horizontally. But as we’ve seen, this isn’t necessarily the case across languages: time is a complicated concept, and can be expressed through a variety of metaphors. Indeed, as any language learner knows, languages aren’t just sets of words, but rather bring with them a whole new way to view the world. That’s just one of many reasons why learning a language is such a great use of your time — whether that time be above you, below you, in front of you, or behind you.

Scire linguas: Why knowing your Latin can help your language skills

Thanks to London Translations for today’s blog post about the value of learning Latin!

Latin, a language that is more than 2,000 years old and is still spoken in the Vatican today, has shaped modern European languages like no other. Who would’ve thought that this medium of communication, which spread through the power of the Roman Empire, would influence language as we know it, speak it and understand it worldwide?

But why bother with learning Latin? If you don’t want to work in the Vatican, why should you learn a dead language? Surely you might as well focus on learning a modern language that actually helps you to communicate with other human beings, whether you’re travelling the world, writing emails or letters, or having business meetings with international clients.

However, despite being so old, Latin can give your language skills a real boost and help with a range of tasks, including consecutive interpreting. Why? Let’s take a closer look.

Better vocabulary

It’s a fact that almost 50 per cent of English vocabulary comes from Latin and 20 per cent from Greek. So if you know your Latin, you can derive an array of English words and improve your vocabulary in general. This applies to other European languages as well.

Better grammar

By getting to grips with Latin grammar, you can gain a better understanding of what grammar is about and how to apply that knowledge to other languages, making it easier to identify grammatical differences in a variety of languages.

Better learning of modern languages

If you know your Latin, it will be easy for you to apply your grammar and vocabulary skills to the modern Romance languages, such as Spanish, French, Portuguese and Italian. In fact, around 40 languages are connected to Latin. That is a big pool of knowledge.

Better performance in tests

People who know Latin generally outperform people who don’t in standardised tests. This may be because a language that has so many rules can help to shape logical thinking and cognitive skills in general.

Better foundation for different career paths

Knowing Latin and Greek can help to enhance your chances of succeeding in different career paths. In some professions, it is especially beneficial. Think of medicine, the law and philosophy.

As you can see, learning Latin has numerous advantages. It is not only a language for old, sophisticated men who sit in libraries all day. It is a language we should not forget and something that is well worth teaching future generations.

(In case you wondered what ‘scire linguas’ means, it translates as ‘learn languages’.)

If you’d like to try out a bit of Latin, you can find a free demo on our website.

Book review: Through the Language Glass

Ever wondered what us language geeks do for fun in our spare time? Reading books about languages, of course! Well, not all the time – but I recently read the very interesting Through the Language Glass by Guy Deutscher, and would recommend it to anyone else who is interested in how different languages work, and how our mother tongue affects our thoughts and behaviour.

Through the Language Glass is all about the ongoing linguistic debate about whether our native language affects our perception and the way we think about the world around us. A large portion of the book is dedicated to a rather in-depth discussion about the differences between colour vocabulary in various languages. You might already know that Russian and Italian have two words for ‘blue’ (light and dark blue). But you might not know that the famous Greek writer Homer didn’t have any words for blue, and instead used mostly red and black to describe the scenes of the Iliad. This led to a long debate about whether people in the past lacked our modern ‘colour sense’ and saw the world in only a few shades. You’d probably have to be pretty dedicated to trying to understand the evolving debate on the development of linguistic terms for colours to plough through this rather long section, but it is rather interesting if you’ve got the patience.

Through the Language Glass is all about the ongoing linguistic debate about whether our native language affects our perception and the way we think about the world around us. A large portion of the book is dedicated to a rather in-depth discussion about the differences between colour vocabulary in various languages. You might already know that Russian and Italian have two words for ‘blue’ (light and dark blue). But you might not know that the famous Greek writer Homer didn’t have any words for blue, and instead used mostly red and black to describe the scenes of the Iliad. This led to a long debate about whether people in the past lacked our modern ‘colour sense’ and saw the world in only a few shades. You’d probably have to be pretty dedicated to trying to understand the evolving debate on the development of linguistic terms for colours to plough through this rather long section, but it is rather interesting if you’ve got the patience.

The rest of the book moves on to some interesting discussions of smaller tribal languages in Australia and elsewhere, and how their unique features either reflect the requirements of the society/location, or affect the behaviour of the speakers. For example, the Aboriginal language Guuguu Yimithirr has no words for left and right. Instead, speakers must develop an acute sense of North, South, East and West, as it’s impossible for them to say ‘the tree is on my left’ – instead they must say ‘the tree is North of me’. Experiments have shown that even if speakers of the language are driven to new locations blindfolded, they retain their incredible sense of direction and can still describe location based on the compass directions.

And how about grammatical gender? For us English speakers, referring to a table as ‘she’, as a Spanish speaker would (la mesa), or a girl as ‘it’, as a German would (das Maedchen), seems rather odd. But for most Europeans, using a blanket ‘it’ for everything doesn’t really feel right either. So what does this mean for all those speakers of languages with grammatical gender? Do they somehow see a table as girly and feminine, and a phone (el teléfono in Spanish) as macho and masculine? Well of course not… that would be silly! But there may be subtle ways in which these distinctions affect us. Think about how we can tell a story in English being vague about the gender of the person involved. Yesterday, I had dinner with my friend. Whether that friend is male or female is none of your business! But in Spanish, you’re rather forced to disclose that ‘la amiga’ was of course a girl.

We might find the idea of a ‘gender’ for inanimate objects strange and funny, but Deutscher traces this back to at least an original logical starting point. It might surprise you to know that there are many more genders in language, beyond the masculine, feminine and neutral genders you might already know. Some languages even have a ‘vegetable’ gender, which even includes things like aeroplanes. Why, you might ask? Well, it’s simple really. The ‘vegetable’ gender may have started off for only plants. This would have included wood, and anything made from wood, such as a boat, perhaps. It’s then not such a jump to having other vehicles in the same gender.

If any of this sounds intriguing and you’d like to know more, I recommend that you pick up Deutscher’s book. It’s not quite beach reading, but it’s accessibly written, not an academic tome that’s only for linguists. I can guarantee that you’ll learn something new about languages and maybe gain a different perspective on how your native language affects your perception.

Alex