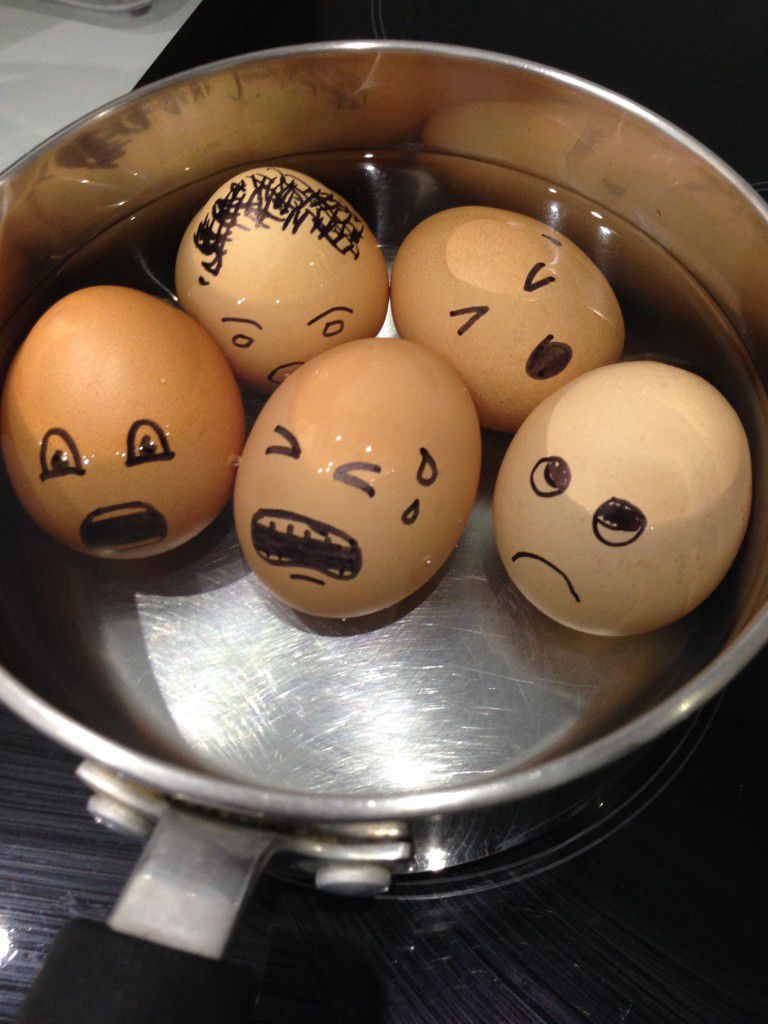

Lost, drowned, in a shirt… how do you like your eggs?

Happy World Egg Day!

English is quite a boring language when it comes to eggs. We boil them, scramble them, poach them, fry them. All very ordinary.

Which is why we were delighted to discover that other languages are more dramatic in their approach to eggs!

Over to Italy:

For Italians, poached eggs are literally ‘eggs in a shirt’ – ‘le uova in camicia’ – possibly because the frilly poached egg white looks like the sleeves of a loose blouse.

Alternatively (but still quite theatrically), you can call them ‘le uova affogate’ (literally ‘drowned eggs’). Poor old eggs!

And now to Germany:

Maybe it’s the same idea of drowning that makes Germans call their poached eggs ‘verlorene Eier’ – ‘lost eggs’. The eggs, like sailors lost at sea, drown quietly in the saucepan.

Or, if it’s a fried egg you’re after, the Germans have a pretty expression for that too: ‘Speigeleier’, literally ‘mirror eggs’. Can anyone tell us why..?

Bullseye!

In Italian, Slovak and Czech (to name but a few), the fried egg is the ‘bullseye egg’- because, of course, it resembles a bullseye (or a porthole, which is the same word): ‘le uova all’occhio di bue’ (Italian), ‘volské oko’ (Slovak), ‘volská oka’ (Czech).

Eyes in a pan?

A similar idea, though slightly more graphic, applies in Bulgarian and Slovenian where the fried eggs (‘яйца на очи’ and ‘jajce na oko’ respectively) translate as ‘eggs eye-style’! So next time you fry an egg, you may choose to remember this vocabulary by imagining a big eyeball staring up at your from the plate… OR you may choose to stick to the safe, if rather boring, English equivalent.

Got any other interesting egg-related vocabulary? Let us know!

5 times you spoke Italian and didn’t know it

Did you know that you speak Italian?

No, really – you do. And we don’t just mean that time you ordered a pizza. Here are a few words you’ve probably used at some point, but might not have realised were Italian:

Novella

Longer than a short story, but not quite a full novel. Well-known novellas include John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis) by Franz Kafka and Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decamerone (The Decameron). The word ‘novella’ comes from the Italian meaning ‘new’.

Paparazzi

The use of this term to describe photo-journalists who follow and take pictures of celebrities can be traced back to a character in Federico Fellini’s 1960 classic movie, La Dolce Vita. Reports vary as to why Fellini chose this name for the independent photographer in the film, but one version of events claims it’s a word from an Italian dialect describing the annoying noise made by a small insect.

A cappella

Anyone who’s seen Pitch Perfect will know that a cappella means singing without any musical accompaniment, but its literal meaning in Italian is ‘in the manner of the chapel’. And it’s not the only Italian word used in music; the list is seemingly endless but a few examples are piano (quiet), allegro (lively and fast), crescendo (getting louder) and lacrimoso (sad).

Tarantula

The first spiders to be called ‘tarantulas’ were named for the Italian city of Taranto, where they were first found. Interestingly, these weren’t the hairy beasties we call tarantulas today, but what are now known as wolf spiders. (Not that we’d want to find either of them in our house.) Many people in southern Italy during the 16th and 17th century believed that a bite from the spider would cause a hysterical condition called tarantism, which could only be cured by dancing the tarantella.

Graffiti

Graffiti comes from the Italian word ‘graffito’, which means ‘scratched’, and in art history the term is used to describe work created by scratching designs onto a surface. The word dates back to the 19th century, when it was used to describe inscriptions and drawings found in the ancient ruins of Pompeii, and today has taken on a mostly negative connotation – no matter how skilful the artist, graffiti is generally considered synonymous with vandalism.

There are plenty more examples of Italian words that have found their way into other languages – among them:

Stiletto: from the Italian word ‘stilo’, meaning ‘dagger’.

Mafia: its origins are uncertain, but many believe it to be from the Sicilian word ‘mafiusu’, which means ‘swagger’ or ‘bravado’.

Extravaganza: a spectacular theatrical production, which takes its name from the Italian word ‘stravaganza’ (extravagance).

Quarantine: derived from ‘quaranta’, the 40 days of isolation required to try and halt the spread of the Black Death in the 14th century.

How many Italian words have you used recently…?

Language of the week: Italian

Buongiorno!

Italian is our language of the week, in celebration of an annual tradition, Il Palio, which dates back to the 12th century and is held on the 16th of August.

This is a horse race unlike any other, and is all over in 90 seconds. It’s held in the beautiful city of Siena, where the 17 districts compete against each other for the glory. Amazingly a district can still win if the horse loses their jockey during the race, as long as they’re over the finish line first (this has actually happened 23 times since records began). If you have a chance to visit Siena while the Palio is on, you should go – the main square is filled with flags from each district and there is an incredible atmosphere throughout the whole town.

This is a horse race unlike any other, and is all over in 90 seconds. It’s held in the beautiful city of Siena, where the 17 districts compete against each other for the glory. Amazingly a district can still win if the horse loses their jockey during the race, as long as they’re over the finish line first (this has actually happened 23 times since records began). If you have a chance to visit Siena while the Palio is on, you should go – the main square is filled with flags from each district and there is an incredible atmosphere throughout the whole town.

If you want to see just how much the Palio is celebrated in Siena have a look at this…

Here are some of the best things we’ve discovered this week about Italian:

- One of the longest words in Italian is ‘precipitevolissimevolmente’ which means ‘extremely quickly’.

- This Italian tongue twister: ‘Trentatré Trentini entrarono a Trento, tutti e trentatré trotterellando’… which means ‘thirty three Trentonians came into Trento, all thirty three trotting.’

- The word ‘Gelato’ means Italian style ice cream (different to normal ice cream for a number of reasons; firstly it is made with a higher proportion of milk to cream, secondly it has a slower churning process and finally it is served at a slightly warmer temperature than ice cream). Gelato is potentially one of the most important words to know in Italian, as the ice cream cone is an Italian invention and Italy is famous for its Gelato. There’s even an ice cream university in Bologna (Carpigiani Gelato University).

- Italian is a Romance language, meaning it has a Latin origin. Gesture could also be considered important to the Italian language, as messages are often conveyed using hands and facial expressions. When in Italy, you’ll probably hear people saying ‘Ciao Bella!’ to each other as a friendly greeting – but if you don’t want to be too familiar, you may wish to stick to ‘Buongiorno’ (good day) the first time you meet someone.

- The Italian alphabet has twenty-one letters in it. It does not include the letters J, K, W, X and Y; these letters can only be found in foreign words that are common in everyday Italian writing.

- To wish someone good luck in Italian, you should say, ‘In bocca al lupo!’, which translates literally as ‘In the mouth of the wolf’. The correct response to this expression is, ‘Crepi il lupo!’, which means ‘May the wolf die!’

Do you have a favourite Italian word or phrase? We would love to hear from you, so feel free to comment below, tweet us @EuroTalk or write to us on Facebook! And if you’d like to learn some Italian, why not try our free demo, or download our uTalk app to get started.

Alex

Breaking the ice: overcoming language nerves

So apparently a quarter of Brits are nervous about speaking another language when they’re abroad, and 40% of us are embarrassed by our language skills.

These conclusions come from a study by the British Council, which surveyed 2,000 British adults. While 67% of respondents believed it’s important to learn a few words of the local language before a trip, it seems not many of us are putting that into practice when we actually get there.

What if?

There are a number of very legitimate reasons for this fear:

‘What if I get it wrong and everyone laughs at me?’

‘What if I say my bit perfectly, but then don’t understand the response?’

‘What if they just don’t understand what I’m trying to say?’

‘What if I open my mouth and my mind goes blank?’

We all hate the idea of making a fool of ourselves, and it doesn’t help that the Internet is full of stories about people who said ’embarazada’ (pregnant) when they meant to say ’embarrassed’. (Probably more embarrassing than the thing you were embarrassed about in the first place, ironically.) But how many of those people would make the same mistake again? I’m guessing zero.

It sounds like a cliché, but sometimes making a mistake really is the best way to learn. And in my experience, even if you do get things wrong, and even if people laugh, it won’t be mean laughter – and they’ll probably go out of their way to explain where you went wrong, so you know for next time.

Most likely, whoever you’re speaking to will probably be pleasantly surprised that you gave it a try in the first place; in most countries, not much is expected of British or American visitors, so any time we make the effort, it’s appreciated. (Just look at the response to Mark Zuckerberg speaking Mandarin – even though he was very hesitant, and made lots of mistakes, the audience loved it.)

What’s the point?

But at least feeling anxiety over speaking another language shows an interest in trying, and a desire to get it right; the fear of making mistakes is what’s holding us back. The far bigger problem is the number of people who believe there’s no point at all in learning another language, because ‘everyone speaks English’, ‘every time I try, people reply to me in English’ and ‘just knowing a few words won’t help’.

It’s true – last year, when I visited Italy, everyone could tell instantly that I was British, and even if I started a conversation in Italian, they would generally reply to me in English. But here’s the thing: though it’s very easy to seize that lifeline and lapse back into English, you don’t have to. I had very little Italian, but I was determined not to give up, even though the opportunity was there – and the waiters and shop staff I was trying to speak to soon caught on and reverted to Italian. Our conversations mostly consisted of one-word sentences, but at least they were Italian words, and we were able to understand each other. And I was pretty proud of myself afterwards – much more than I would have been if I’d had the same conversation in my native language.

As for everyone speaking English, that’s clearly not true – and it shouldn’t matter anyway. The comments on the BBC article about the British Council study show that we expect those who visit the UK to speak English – so why should it be any different when we travel to another country? Even if you don’t need to learn a language, does that mean you shouldn’t?

As for everyone speaking English, that’s clearly not true – and it shouldn’t matter anyway. The comments on the BBC article about the British Council study show that we expect those who visit the UK to speak English – so why should it be any different when we travel to another country? Even if you don’t need to learn a language, does that mean you shouldn’t?

And finally, it’s true that knowing a few words wouldn’t help you if you had to go and close a business deal in French, or teach maths in China. But if you’re just going on holiday for a week, the chances are that as long as you’re able to check in to your hotel, order a meal and buy a bus ticket, you’re probably covered – though of course it will depend where you’re travelling to.

This, of course, is the whole idea that uTalk is built on. Because sometimes, just being able to say hello in another language is enough to make someone smile. And why wouldn’t we want to do that?

So let’s be bold, and show off our language skills. And let’s see if we can bring those percentages down in time for the next study.

Liz