Learn Chinese? No problem for our Junior Language Challenge semi-finalists!

As a EuroTalk newbie, I had no idea what to expect when it came to the Junior Language Challenge. I have heard a lot of stories (all good, I promise) over the last couple of months on what to expect at the semi-finals. We did a few practice rounds here at the EuroTalk office and I thought we had all done pretty well at getting the hang of Chinese, considering how hard the body game was! However, after the first round at my first semi-final, I realised that we were actually all pretty awful.

For those of you who are also new to the Junior Language Challenge, it is an annual competition for children who are under 11 years old. It runs from March until October, where the final is held at Language Show Live, London Olympia. Over this period, the children participating learn three languages. This year we chose Portuguese, Chinese and Arabic, three very different and difficult languages to learn. However, the children did not appear to struggle at all; the scores were amazing across all the semi-finals, with children regularly scoring top marks in the games.

There was a lovely atmosphere at the semi-finals I visited, and both hosting schools were fantastic at making everyone feel welcome (as well as providing us EuroTalkers with a fabulous lunch). The children, teachers and the parents were clearly buzzing with excitement and nerves. Every child put 100% effort into the games, even in the rounds which they made clear were not their favourites!

Even though it’s a competition, it was clear to see there were no hard feelings between the children. All were delighted to receive a goodie bag and a medal, and were eager to find out the final language. The whole thing was organised brilliantly by our marketing manager Liz, and couldn’t have happened without the support of all the schools, pupils, parents and teachers involved; so we thank you all for this! You have also helped us to raise nearly £6,000 for onebillion, who aim to bring education to some of the world’s poorest countries by developing apps. These apps are in the children’s native language and help them to learn maths, English and how to read. This money will help to continue onebillion’s amazing work in Malawi and change the lives of so many children.

The JLC is far from over yet! With the final less than 3 weeks away, on October 16th, the children now have the tough job of learning Arabic for their third language. The 33 finalists will go head to head at London Olympia, for the title of Junior Language Challenge champion 2015, in what promises to be a nail-biting competition. The winner will be going on a family holiday to Africa and we wish everyone taking part in the final the best of luck!

Are you coming to Language Show Live this year? If so, please do come up to seminar room 3 on Friday morning to watch the JLC final – everyone’s welcome!

Alex

Talking about Time: Insights from Other Languages

The following post is from Paul, an English teacher who lives in Argentina. Paul writes on behalf of Language Trainers, a language teaching service which offers foreign-language level tests as well as other free language-learning resources on their website. Check out their Facebook page or send an email to paul@languagetrainers.com for more information.

If you love languages, and you’d like to guest blog for EuroTalk, please get in touch; we’d love to hear from you.

Talking about Time: Insights from Other Languages

Time: it’s an essential part of our everyday life, and we talk about it constantly — yet we can’t see or touch it. In English, we usually conceptualize time as a linear distance along a horizontal plane. This seems totally natural to us: time can be long or short, deadlines can be close to us or far away from us, and we have no problem representing minutes and hours on a timeline.

Image via Pexels

But as common as these expressions are, they raise some important questions about how we express time through language. As we’ll see, we often use conflicting metaphors to describe the passage of time. And other languages express time in a completely different way, challenging this anglocentric notion of time that seems so natural to English speakers.

Does time move around us, or do we move through time?

There’s no question that our relationship to time is a dynamic one: days pass, we get older, and the future becomes the past. But who’s doing the moving: time, or us? Expressions like “time flies” or “the hour dragged on” suggest that time moves and takes us with it. Indeed, if we talk about an upcoming test — “The final exam is getting closer” — we can certainly phrase it in terms of time moving towards us.

But we can also talk about the same test by saying “We’re getting closer to the exam date”. Suddenly, the relationship is flipped: now time is static, and we’re moving through time into the future. Indeed, language enables us to conceptualize time in terms as a static entity that we move through, as well as a dynamic entity that moves around us.

In just the English language, we have already found some peculiarities about how we express time. But when we introduce other languages into the equation, the picture gets even more interesting.

Is time horizontal or vertical?

In English, regardless of whether time moves towards us or we move through time, this movement is definitely horizontal. The words we use to describe time — “push back” a deadline, “be ahead” of schedule — are the same ones we use to describe horizontal distances (e.g., “take a step back”, “walk ahead of her”). That is, for English speakers, time is horizontal, with the past behind us and the future in front of us.

But this isn’t necessarily the case in Mandarin Chinese. For Mandarin speakers, it’s possible to talk about time in the same way as English speakers, with time running along a horizontal plane. But it’s also common to use vertical terms to describe the order of events, days, semesters, etc. For instance, the words shàng (up) and xià (down) can be used to express temporal relations: xià ge yuè means “next month”, and shàng ge yuè means “last month”.

Thus, in Mandarin, our familiar horizontal timeline can be flipped vertically, with the past being up and the future being down.

Is time a distance or a quantity?

Two classic ways to express time are the timeline and the hourglass. However, these point to starkly different metaphors. Whereas a timeline suggests that time is a distance, an hourglass suggests that time is a quantity. In English, we generally prefer to talk about time as a distance — saying that something “lasts a long time” is more common than saying it “lasts a lot of time”.

Image via Pixabay

In Spanish, however, this isn’t the case. Indeed, saying tiempo largo (literally “long time”) sounds odd in most dialects; instead, mucho tiempo (“a lot of time”) is much preferred. Greek, too, features this tendency to use volume-oriented metaphors, using words like megalos (“large”) and poli (“much”).

Thus, whereas in English, our use of language favors the timeline, other languages like Spanish and Greek make greater use of the hourglass in their temporal expressions.

Is the past in front of us or behind us?

In English, we can look back into the past and forward into the future. This is as clear as day to us: the past is behind us, and the future is in front of us. Yet in spite of how obvious this may seem to us, this isn’t the case in all languages.

Take Aymara, an Amerindian language spoken in some regions of Bolivia, Peru, and Chile. In Aymara, the past is described as being in front of us, whereas the future is behind us. Though this conception of time seems jarring to us English speakers, it’s logical: we can see in front of us, just as we can remember the past; but we can’t see behind us, just as we can’t predict the future.

To our English-speaking brains, it seems only natural that time is a distance that moves horizontally. But as we’ve seen, this isn’t necessarily the case across languages: time is a complicated concept, and can be expressed through a variety of metaphors. Indeed, as any language learner knows, languages aren’t just sets of words, but rather bring with them a whole new way to view the world. That’s just one of many reasons why learning a language is such a great use of your time — whether that time be above you, below you, in front of you, or behind you.

6 language family trees that will make you want to learn them all

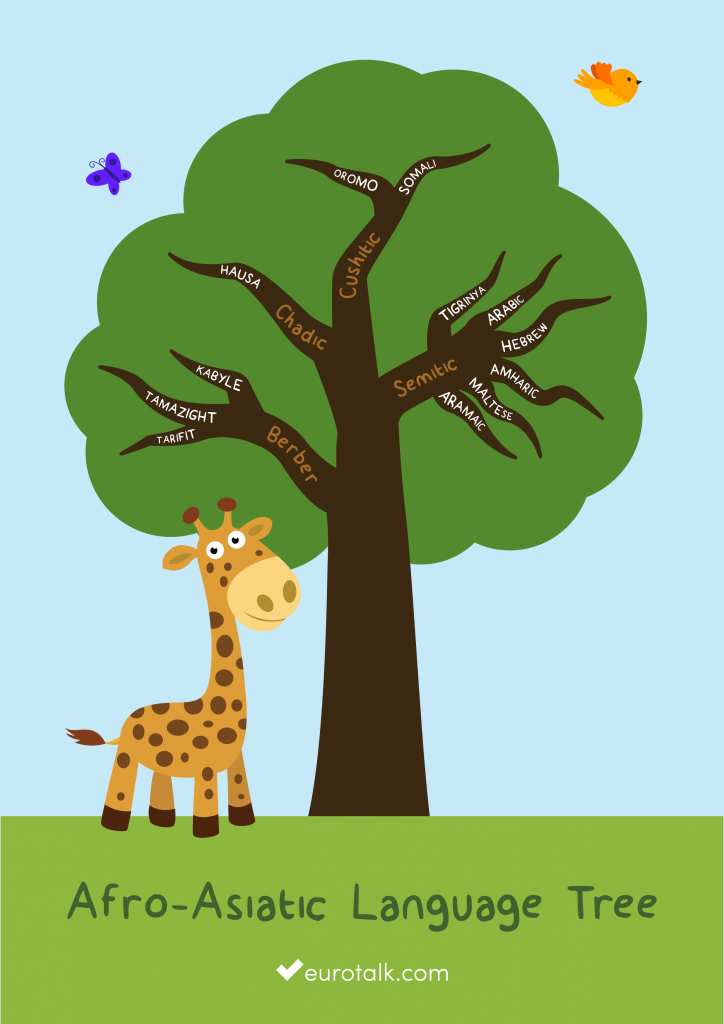

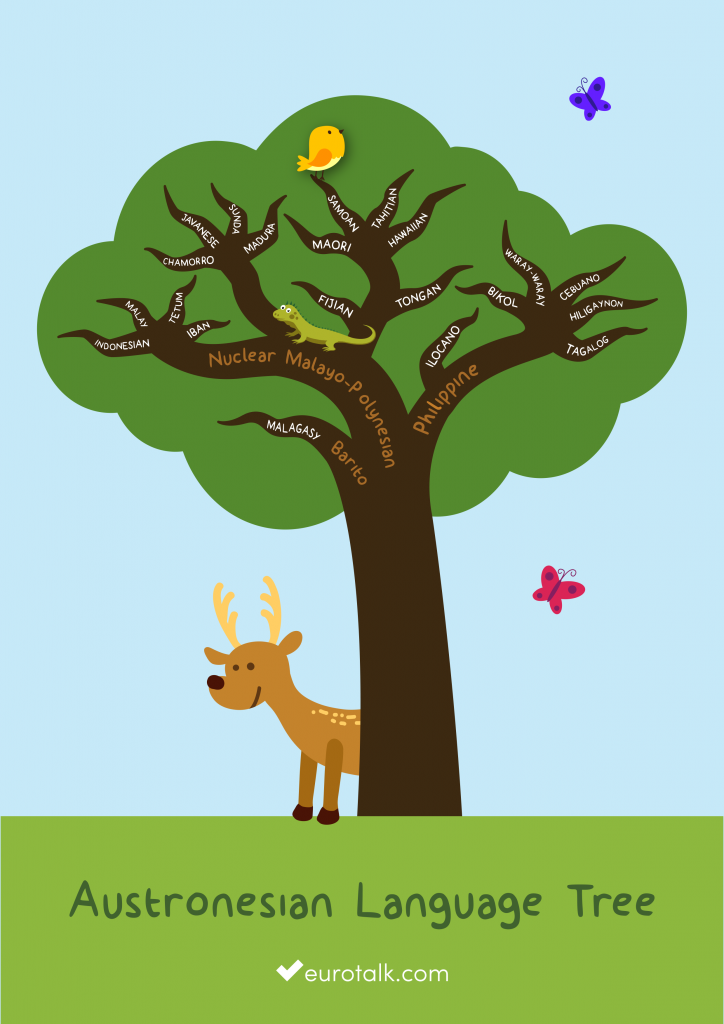

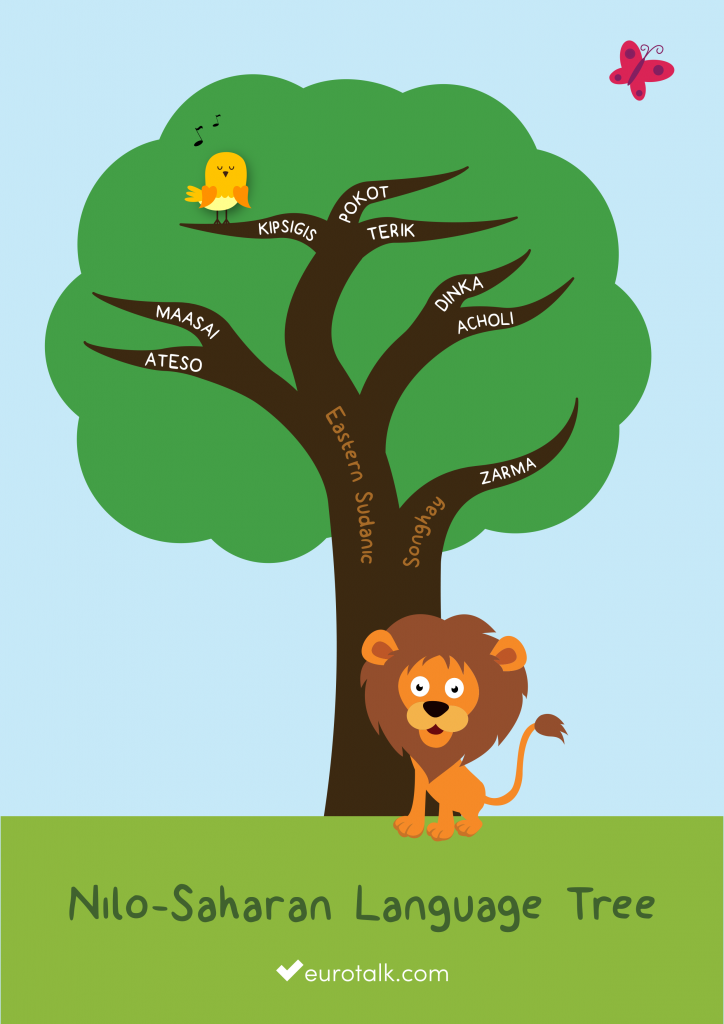

We recently shared an illustration showing many of the world’s languages and how they’re all related to each other. And a lot of you really liked it, so we thought we’d give you a closer look at each language family.

With some familiar names and some not quite so familiar, these illustrations show the staggering variety of languages spoken in the world (and this isn’t even all of them!). We’re always fascinated to learn about new or unusual languages, so please do get in touch if you’d like to tell us about yours.

And if you’d like to share any of the images below, please do 🙂

Afro-Asiatic

Austronesian

Indo-European

Nilo-Saharan

Sino-Tibetan

Turkic

Breaking the ice: overcoming language nerves

So apparently a quarter of Brits are nervous about speaking another language when they’re abroad, and 40% of us are embarrassed by our language skills.

These conclusions come from a study by the British Council, which surveyed 2,000 British adults. While 67% of respondents believed it’s important to learn a few words of the local language before a trip, it seems not many of us are putting that into practice when we actually get there.

What if?

There are a number of very legitimate reasons for this fear:

‘What if I get it wrong and everyone laughs at me?’

‘What if I say my bit perfectly, but then don’t understand the response?’

‘What if they just don’t understand what I’m trying to say?’

‘What if I open my mouth and my mind goes blank?’

We all hate the idea of making a fool of ourselves, and it doesn’t help that the Internet is full of stories about people who said ’embarazada’ (pregnant) when they meant to say ’embarrassed’. (Probably more embarrassing than the thing you were embarrassed about in the first place, ironically.) But how many of those people would make the same mistake again? I’m guessing zero.

It sounds like a cliché, but sometimes making a mistake really is the best way to learn. And in my experience, even if you do get things wrong, and even if people laugh, it won’t be mean laughter – and they’ll probably go out of their way to explain where you went wrong, so you know for next time.

Most likely, whoever you’re speaking to will probably be pleasantly surprised that you gave it a try in the first place; in most countries, not much is expected of British or American visitors, so any time we make the effort, it’s appreciated. (Just look at the response to Mark Zuckerberg speaking Mandarin – even though he was very hesitant, and made lots of mistakes, the audience loved it.)

What’s the point?

But at least feeling anxiety over speaking another language shows an interest in trying, and a desire to get it right; the fear of making mistakes is what’s holding us back. The far bigger problem is the number of people who believe there’s no point at all in learning another language, because ‘everyone speaks English’, ‘every time I try, people reply to me in English’ and ‘just knowing a few words won’t help’.

It’s true – last year, when I visited Italy, everyone could tell instantly that I was British, and even if I started a conversation in Italian, they would generally reply to me in English. But here’s the thing: though it’s very easy to seize that lifeline and lapse back into English, you don’t have to. I had very little Italian, but I was determined not to give up, even though the opportunity was there – and the waiters and shop staff I was trying to speak to soon caught on and reverted to Italian. Our conversations mostly consisted of one-word sentences, but at least they were Italian words, and we were able to understand each other. And I was pretty proud of myself afterwards – much more than I would have been if I’d had the same conversation in my native language.

As for everyone speaking English, that’s clearly not true – and it shouldn’t matter anyway. The comments on the BBC article about the British Council study show that we expect those who visit the UK to speak English – so why should it be any different when we travel to another country? Even if you don’t need to learn a language, does that mean you shouldn’t?

As for everyone speaking English, that’s clearly not true – and it shouldn’t matter anyway. The comments on the BBC article about the British Council study show that we expect those who visit the UK to speak English – so why should it be any different when we travel to another country? Even if you don’t need to learn a language, does that mean you shouldn’t?

And finally, it’s true that knowing a few words wouldn’t help you if you had to go and close a business deal in French, or teach maths in China. But if you’re just going on holiday for a week, the chances are that as long as you’re able to check in to your hotel, order a meal and buy a bus ticket, you’re probably covered – though of course it will depend where you’re travelling to.

This, of course, is the whole idea that uTalk is built on. Because sometimes, just being able to say hello in another language is enough to make someone smile. And why wouldn’t we want to do that?

So let’s be bold, and show off our language skills. And let’s see if we can bring those percentages down in time for the next study.

Liz