‘Zewg birer, jekk joghgbok’ (or How to say ‘2 beers please’ in Maltese)

Katherine is one of our uTalk Challenge participants; she chose to learn Maltese in preparation for her holiday in the sunshine! Here she shares a few of her language adventures, and explains why she found knowing a little bit of the local lingo made the trip even more enjoyable.

Learning Maltese probably counts as one of the more pointless things you could do in life, as it is only spoken in two small islands, where everybody speaks very good English. But being in the position of having a week’s holiday booked in Malta for the last week of January, it seemed like the perfect thing to do for January’s uTalk challenge; after all, it is a language, and a very interesting-sounding one at that – it appears to be a mixture of Italian, English and Arabic. And what a great place to visit in January too, with the sun shining and temperatures in the high teens.

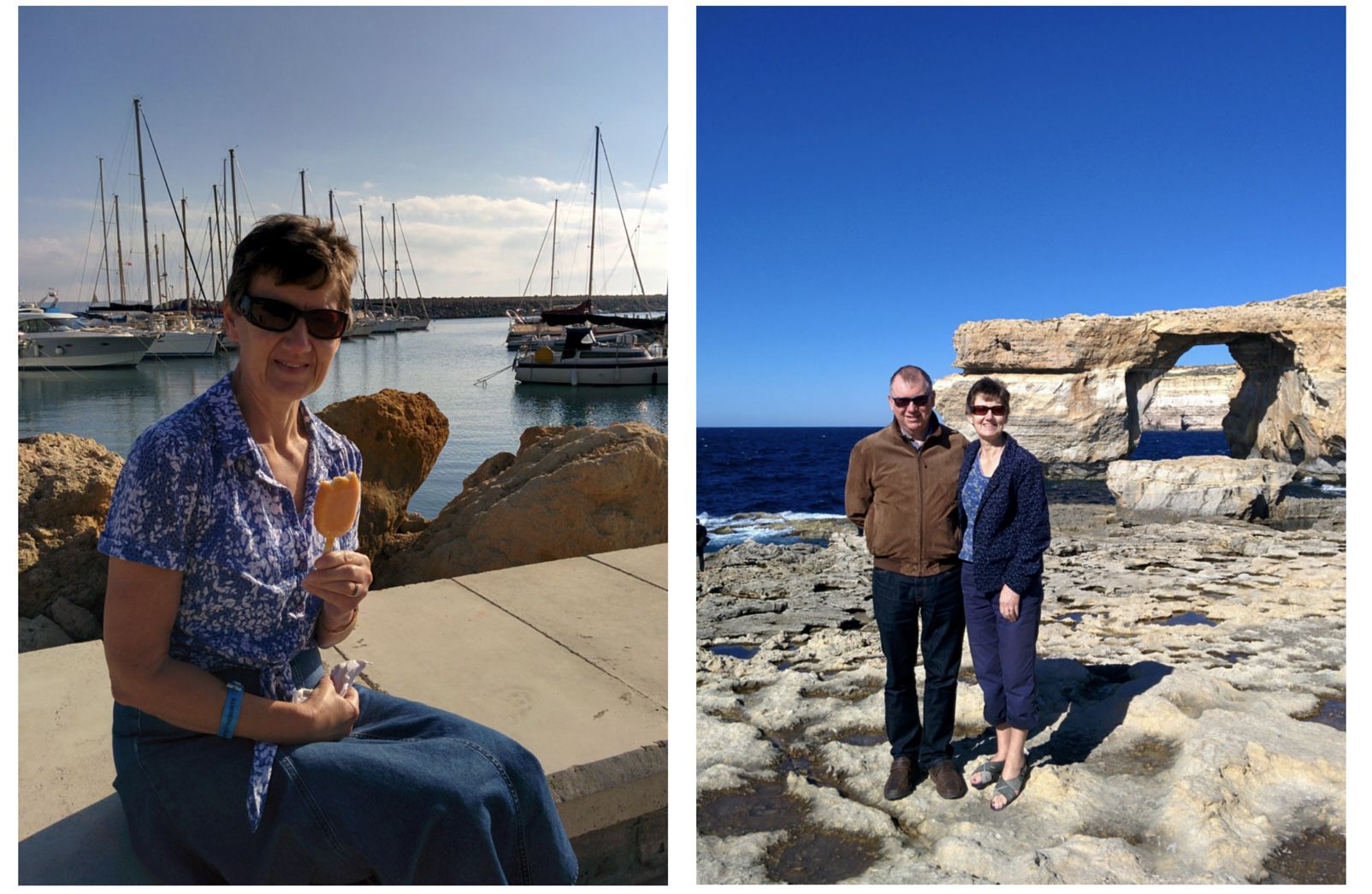

So here I am with my “gelat” (ice cream) in front of Mgarr in Gozo (the harbour where the little ferry arrives from Malta, just a couple of miles away), with some people talking on a “dghajsa” (boat) behind me, and the “xemx” (sun) shining brightly. And then with my husband at the “Tieqa Zerqa” (the Azure Window), which is one of the features shown in the final uTalk topic about the country. That section is great when you actually get to the country, as you can recognise places and know how they should be pronounced. In fact, having got the gist of how the combinations of letters are pronounced, it was great fun to be able to say the place names and street names and even read some notices, picking out the odd word or two.

It was on our outing to Gozo that I had my highlight of the week, language-wise. I was able to order some coffees, one black and one with milk and some local snacks (also featured in the Malta topic, so I knew they were the local delicacy)! I also asked for the bill and said goodbye etc; this all delighted the elderly lady serving us, in fact maybe we made her day! Not quite such success later that same day, when I came to use the phrase top of any uTalker’s list – “Zewg birer, jekk joghgbok” (2 beers please). I thought I had said it wrong, but it turned out the waiter was from Serbia!

So, even though it was not at all necessary to learn Maltese to visit Malta, it definitely enhanced my holiday to be able to do so a little bit. And what’s more, even though I suspected I had been learning the words and phrases just to amass the points and they wouldn’t stick, I found that they kept popping into my mind, so in fact they had stuck!

A great challenge, and I’m looking forward to next month’s new language!

Are you a language geek?

We’re proud to be language geeks here at EuroTalk, but we know we’re not the only ones! Here’s your opportunity to show us what you know… Can you get 100%? And more importantly, can you beat your friends? 😉

(By the way, if you want to cheat on any of the questions, the words we’ve used in the quiz are in our uTalk app – now available in 100 languages on iPad, iPhone and iPod touch.)

8 bizarre superstitions from around the world

This month, we’ve been having a look at interesting superstitions from different countries. There are literally thousands of examples – here are just a few. We suggest they should be taken with a pinch of salt…

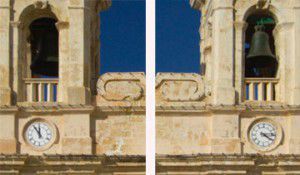

If you’re in Malta, don’t rely on the church clock to tell you the right time. Churches are sometimes fitted with two clocks that tell different times to confuse the Devil about the time of the service.

Approach toilets with caution in Morocco – there might be a genie living in the u-bend… They don’t give wishes and they certainly don’t like to be disturbed. If you need to go, just say the words ‘Rukhsa, ya Mubariqin’ (With your permission, O Blessed Ones). Also beware of going to the toilet at night, where you might run into a beast called ‘Maezt Dar L’Oudou’, the ‘Goat of the Lavatories’.

If you’re visiting Britain, you’ll probably find you need an umbrella with depressing regularity. But whatever you do, don’t open it till you get outdoors; it’s very bad luck to open your umbrella inside.

Elves are alive and well in Iceland. In a 2006 survey only 35% of Icelanders said that they thought the existence of elves was either impossible or very unlikely and local elves still take an active role in shaping modern Iceland: roads and building projects sometimes have to be changed to avoid destroying known elf homes.

In Japan, if you walk by a graveyard or a hearse passes you, you must tuck your thumbs inside your fists. This is because the Japanese word for thumb (‘oya yubi’) literally translates as ‘parent-finger’ and so by hiding them you protect your parents from death.

Ready to go? Have a seat. In Russia, if you’re going on a journey you have to sit down for a minute just before leaving the house, to reflect on the coming trip and make sure you’ve got everything you need. It’s also bad luck to say goodbyes over the threshold, so you should always say your farewells before you leave.

If you find yourself in Spain on New Year’s Eve, don’t be surprised if, when the clock strikes midnight, you notice everyone around you eating grapes. This has been a tradition since the early 20th century; eating one grape for each bell strike is believed to bring twelve months of good luck.

And finally, when in China, never leave rice on your plate at the end of a meal – for each grain left at the end of a meal, your future husband or wife will have that many pockmarks on their face.

We’d love to hear any more examples, so please do share them in the comments below. And good luck out there…

Pure and simple?

Recently, Alex wrote about the way languages borrow words from each other. She pointed out that in English, we’re always using words from other languages, sometimes without even realising it, with déjà vu, karate and Zeitgeist being just a few examples.

But is this mixing of languages a good thing, or should languages remain ‘pure’?

Hoji Takahashi, a 71-year-old man from Japan, hit the headlines a few weeks ago when he sued the country’s public TV station, NHK, for the mental distress he’s suffered as a result of them using too many words derived from English. A couple of the examples given were toraburu (trouble) and shisutemu (system).

He’s not alone – many elderly Japanese people have trouble understanding these ‘loan words’, and the government has apparently been under pressure for over ten years to try and do something about the dominance of American English in Japan, which has been growing ever since World War II.

The lawsuit is quite controversial, with some dismissing it as ridiculous and others giving Mr Takahashi their full support. But whatever your view, it does raise an interesting question – one that we at EuroTalk often face when translating the vocabulary for our software. Should we go with the word that people most often use, or the one that’s technically correct in the original language?

It’s a difficult decision, particularly when translating for people who want to learn a language, because we know that we have a responsibility to get it right; language learners are putting their faith in us to teach them the correct words, so they’ll be able to speak to people and won’t be embarrassed by saying the wrong thing. But at the same time, the ‘correct’ word might not be the one that they’ll actually need when they get to wherever they’re going. This is particularly the case with African languages, where many words are adapted from French, and indigenous South American languages, where the Spanish influence is very clear. And it can be frustrating for someone who’s just starting to learn a new language to find that half the words are not actually in that language at all.

A few examples:

– In Maltese, the correct word for ‘airport’ is ‘mitjar’, but everyone says ‘arjuport’.

– In Swahili, although ‘tomato’ is ‘nyanya’, ‘tomato ketchup’ is known as ‘tomato’, although the technically correct translation is ‘kechapu ya nyanya’.

– In Tumbuka, when counting to 20, Tumbuka numbers are used, but beyond 20 the numbers revert to English.

There are many more examples, as we’ve discovered over the years and particularly when working on the translations for the new uTalk app. Each new translation is carefully considered and discussed to decide on the best choice from a practical point of view, selecting the word most people would actually use in real life – even if this means some people, like Mr Takahashi, don’t agree with the final result.

What do you think? Should language learning software teach a language in its purest form, or is it better to learn the words that are most commonly used, even if they’re borrowed from another language?

Liz