Junior Language Challenge – the semi-finals!

Back in March, over 1,100 primary school children from around the UK joined our annual competition, the Junior Language Challenge, learning Italian online. Over the next three months, they scored points in the language games, and then in June the top scorers from each region of the country progressed to the second round.

Not wanting to make it too easy, for their next challenge we asked them to learn the notoriously tricky language of Japanese. Impossible, you might say – how can you expect children under 11 to learn such a difficult language?

As we discovered this week, it’s not impossible at all. Over the last ten days, we’ve been travelling around the country for the regional semi-finals, and have been seriously impressed with what we’ve seen. All the children had clearly worked really hard, and we had several very tense contests in the race to grab a place in the final. There were some familiar faces, and some first-time competitors, and everyone gave it their all. So on behalf of EuroTalk, thank you to all the teachers, parents and most importantly, the children for joining in so enthusiastically.

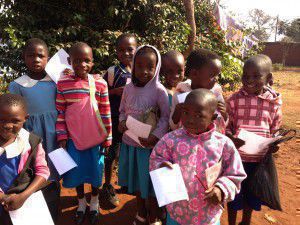

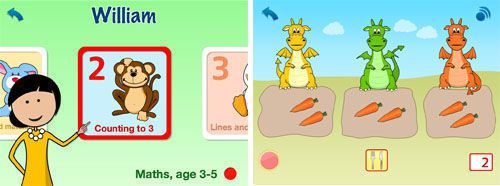

The competition also raised nearly £6,000 for a brilliant organisation called onebillion, who create apps to teach children in developing countries basic maths and reading, giving them valuable learning opportunities that we often take for granted here in the UK. onebillion were recently featured by BBC Click, and their report gives you a taster of the fantastic work they’re doing in Malawi.

But what about our finalists? They’re not finished yet. For their third and final language, they’ll be learning the African language of Somali, ready for the grand final in London next month, where they’ll compete for the title of Junior Language Challenge Champion 2014, and a family holiday to Africa.

We hope that everyone who’s taken part in the JLC this year, whether you’re continuing on to the final or not, really enjoyed it. Now you know that you can learn any language, even difficult ones, the sky’s the limit!

And to our finalists… see you next month 🙂

Languages at primary school – what’s the point?

From September this year, it’s going to be compulsory for primary schools in the UK to teach a foreign language. This is causing quite a lot of stress for schools, according to a report published earlier this week, which says that 29% of teachers don’t feel confident about teaching a language to their students. That’s hardly surprising, considering many teachers haven’t studied languages themselves since their GCSEs, which for some will have been quite a while ago.

But despite this, the report says, 85% of primary schools have said they believe making languages a requirement is a good move, and many are already tackling the situation head on by introducing languages before it’s required by law.

So what exactly is the point of teaching languages at such a young age? Many people will argue that the curriculum for children is already too full, with a need for English, maths and science, as well as citizenship, history and physical education, to name just a few. Why squeeze in yet another subject, especially in a world where many people believe that ‘everyone speaks English’?

So what exactly is the point of teaching languages at such a young age? Many people will argue that the curriculum for children is already too full, with a need for English, maths and science, as well as citizenship, history and physical education, to name just a few. Why squeeze in yet another subject, especially in a world where many people believe that ‘everyone speaks English’?

Learning a language is good for your brain

Well firstly, learning a language can actually make you smarter. The positive effects are well documented – bilingualism makes you better at problem solving, planning and verbal reasoning. Research by psychologists at Penn State University has shown that if you’re bilingual, you’re likely to be better at multi-tasking, because your brain is used to ‘mental juggling’. And other studies have shown that learning another language can help to delay the onset of dementia in later life.

It makes you better at your native language

Studying a second language helps you to understand your own, because it makes you think about how language is formed. Because I grew up speaking English, I don’t really remember learning the rules of the language; they just came naturally. But when I took up Spanish, suddenly I needed to think about grammar, and about how I was structuring sentences, which is much more important in Spanish than in English. For example, in Spanish you can’t end a sentence with a preposition, which made me realise how often I was getting away with this in English. And I would never have even known the subjunctive existed if not for my Spanish studies (although I’m not going to lie and say I use the subjunctive regularly in English!).

Learning a language prepares you for the rest of your life

I don’t just mean learning languages at secondary school, although it’s likely that children who leave primary school with some knowledge of another language will want to continue it when they move on. I mean beyond school – when the time comes to choose degree courses and, even more importantly, find a job. A recent article in The Economist says that employees with a language in the U.S. can earn on average 2% extra, which may not sound like much, but over time can add up to some serious money. Not only that but learning a language will make it easier for you people to go travelling and see the world; it might even help you find the love of your life!

The younger, the better

It’s a common argument that children are better at learning languages than adults; because of the way the brain develops, some scientists believe there’s a ‘critical period‘ for language acquisition. And although there’s plenty of evidence that this might not necessarily be the case (just look at Benny Lewis, who didn’t start learning languages until adulthood, and now speaks twelve languages fluently), I do think there’s something in it; after all children are constantly learning new things, so one more probably won’t phase them. And they’re also in a better position to learn than adults, who are very good at finding other things to do and worry about. (I know I am.)

It’s fun!

Some people might disagree with me here, looking back on their own language classes at school with its endless repetition of vocabulary and verb conjugations. Obviously I’m biased, but I do think learning to speak another language can be really fun if it’s put across in the right way. There are so many exciting ways to teach a language, from songs and TV shows to games and apps. The internet is full of great ideas – have a look at #mfltwitterati on Twitter as a good starting point.

Or check out the Junior Language Challenge, EuroTalk’s national competition for children aged 10 and under across the UK – it’s great fun for children, makes life easy for teachers and raises money for charity all at the same time. Just the other day we received a message from one of our 2013 finalists, who said, ‘It was a great adventure. It’s now set me off to learning languages from all over the world.’

Liz

Why I love the JLC

Many people will already be aware of the national languages competition organised by EuroTalk each year, called the Junior Language Challenge. It’s open to all children aged 10 and under, and gives them an opportunity to learn three new languages and compete against other children from their region and ultimately from across the country.

The JLC starts in March and finishes with the final in October. And it’s a lot of work – from a technical point of view (our programmers have literally had sleepless nights getting the software up and running in time) and in terms of organisation. Running a competition like this isn’t an easy task, and with the semi-finals taking place over the next two weeks and the final still to come, it’s only going to get busier.

But I still love the JLC, and here’s why…

Firstly, the children taking part really enjoy it. It’s lovely for us to see their enthusiasm at the regional semi-finals and the grand final in London. Tension’s always high and sometimes there are even tears, which obviously isn’t a good thing in itself, but it does show how passionate the children have become about the competition. In 2011, Ben Fawcett from Chichester even returned early from his family holiday at Disneyworld to compete in the final – that’s what you call dedication.

Secondly, it gives children a love for languages that they can take with them into their future studies and career, and that they might otherwise have missed out on. Marliese Perks from Edinburgh, who reached the final in 2004, wrote to us shortly before she left for university to study Law and Spanish: ‘The competition inspired me to learn languages … little did I know at that age that Spanish and languages would ultimately become my passion … I can’t say thank you enough, you set me on this path and I am loving every minute of it!’ This is the goal of the JLC – to let children know that they can learn languages, and that it can be fun. Not only that but they don’t have to just learn the ones they’re taught at school; Marliese learnt Spanish, Greek and Saami. I’m not sure how often she uses her Saami these days, but what’s important is the JLC showed her she had the ability to learn it, which I think is pretty inspiring.

And finally, there’s a whole other side to the JLC. Each child who enters pays £2.50, and this money is used to purchase tablet devices for schools in Malawi, where class sizes are so huge, it makes teaching a near-impossible task. A tablet that can be shared by several children will fill the gap left by over-stretched teachers, and as a result will literally change lives. A basic education is something that every child should have, no matter where in the world they are, and the competition not only provides opportunities to youngsters in the UK, but it also makes a huge difference for children in Malawi too. I’m proud to be a part of it – albeit a slightly stressed out, panicked part.

To everyone preparing for a semi-final, good luck! To those who’ve already made it through to the final – congratulations, and see you in October 🙂

And to everyone who’s taken part in the JLC – not only in 2013, but every year – thank you.

Liz

So, did you know you can speak Greek?

Today’s blog post is written by Konstantia Sotiropoulou, who’s been helping us to translate and record our Maths apps in Greek.

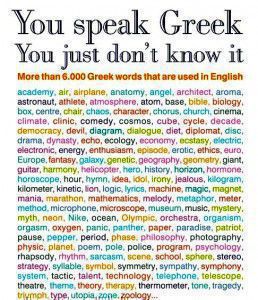

I bumped into the picture below a while ago and I thought this should be interesting. Undoubtedly, Greek is one of the richest languages in the world and is distinguished by an extensive vocabulary. In the past, the Guinness Book of Records ranked the Greek language as the richest in the world with 5 million words and 70 million word types!

The front cover of You speak Greek, You just don't know it, a book by Annie Stefanides (Ianos, 2010)

Well, many of these words have been widely borrowed into other languages, including English. Greek roots are often used to coin new words for other languages, especially in the sciences and medicine. Mathematics, physics, astronomy, democracy, philosophy, athletics, theatre, rhetoric, baptism and hundreds of other words are Greek. Moreover, Greek words and word elements continue to be productive as a basis for coinages: anthropology, photography, telephony, isomer, biomechanics, cinematography, etc. and form, with Latin words, the foundation of international scientific and technical vocabulary, e.g. all words ending with –logy (“discourse”). Interestingly, an estimated 12% of the English vocabulary has Greek origin. Greek has contributed to English in several ways, including direct borrowings from Greek and indirectly through other languages (mainly Latin or French).

In a typical 80,000-word English dictionary, about 5% of the words are directly borrowed from Greek; this is about equivalent to the vocabulary of an educated speaker of English (for example, “phenomenon” is a Greek word and even obeys Greek grammar rules as the plural is “phenomena”). However, around 25% are borrowed indirectly. This is because there were many Greek words borrowed in Latin originally, which then filtered down into English because English borrowed so many words from Latin (for example, “elaiwa” in Greek evolved into the Latin “oliva”, which in turn became “olive” in English).

Greek and Latin are the predominant sources of the international scientific vocabulary. Greek is often used in coining very specialized technical or scientific words, however, so the percentage of words borrowed from Greek rises much higher when considering highly scientific vocabulary (for example, “oxytetracycline” is a medical term that has several Greek roots).

In education, an excellent way to build vocabulary is teaching students how to find roots in words. Since many words have their base in the Greek language, beginning with the roots from this ancient language is a good place to start. This list of English words with Greek origin will give students a basis for further exploration into the roots of the English language.

Now you that you have seen how many Greek words you know, I am going to teach you some more common ones like “kalimera” which means “good morning”, “Ya sou” which means “hi”, “Me lene” which means “my name is” and “efharisto” which means “thank you”. And if you are interested in learning more and discovering how many you already know, try EuroTalk’s uTalk Greek app.

And who am I to be talking about the Greek language? I am the Greek intern of EuroTalk, who translated and recorded into Greek their new Maths apps for young children. An interesting and fun experience for a young translator like me. I have to say that I really enjoyed working in this office, which gives you the sense of a family home. People here are calm and friendly, the kitchen is fully equipped with all kinds of snacks and during the day we get to listen to nice music while working! How amazing is that?

I started towards the end of January by translating the scripts of the app and soon after I recorded the first topics. I caught myself playing the app more than I needed to, as the games are really fun! I am sure young kids will truly enjoy it while learning basic Mathematics rules. And I know that my three-year-old niece, who will be playing the app in a few weeks, will at least have a constructive and educational first contact with technology!

So, whether you want to take up a new language or help your child have a nice start with Maths, you know that EuroTalk is here for you!

* There is an interesting video on YouTube that explains the History of English and the influence that it had from other languages!

Konstantia

French – champion of the language learning world?

I remember the moment when we knew we were officially grown up in primary school – during French lessons with the headmaster.

MFL lessons are the norm nowadays but back in my time, French lessons were a weekly highlight, as they meant me and about a dozen classmates spent half an hour learning something the rest of the school did not already know.

As I moved onto secondary school, languages were eventually deemed ‘uncool’ and those who took French or Spanish past GCSE – myself included – were thought to be insane by their peers.

When I think about it, only French got a shoo-in at primary school. Spanish was introduced in the first year of secondary school but even then, all efforts were concentrated on learning and teaching French.

No-one seemed to care about German or Italian and everyone thought Mandarin was a fruit.

This makes me wonder – when did French become the ‘go-to’ foreign language at school?

This makes me wonder – when did French become the ‘go-to’ foreign language at school?

Learning French is a current requirement in UK primary schools and the possibilities of school trips, exchanges and overseas partnerships are endless, but knowing how to speak it may not be as impressive as learning more obscure languages such as Swedish, Polish or Japanese.

The number of people learning a language nowadays relies on how influential it is in popular culture – just look at how many people have started to learn Na’vi, just because it was featured in James Cameron’s 2009 epic Avatar – and this can only be aimed at the younger generation, when ‘cool’ is key.

This is the aim of our annual language competition for primary schools, the Junior Language Challenge. Parents have commented that the competition has fuelled their children’s passion for learning new languages and has inspired them to take up different ones as options for GCSE.

I am hopeful that more unusual languages will be featured in the National Curriculum, but unless Justin Bieber turns around and starts learning Mandarin, whether pre-teens take language learning to the next step is debatable.

Where do you think today’s language learning is going? Where can there be room for improvement? And ask yourselves, in ten years or so, will French reign supreme or can Spanish or Mandarin take the crown as Most Popular Foreign Language to Learn at Primary School?

Katie