How do you know when you’re fluent in another language?

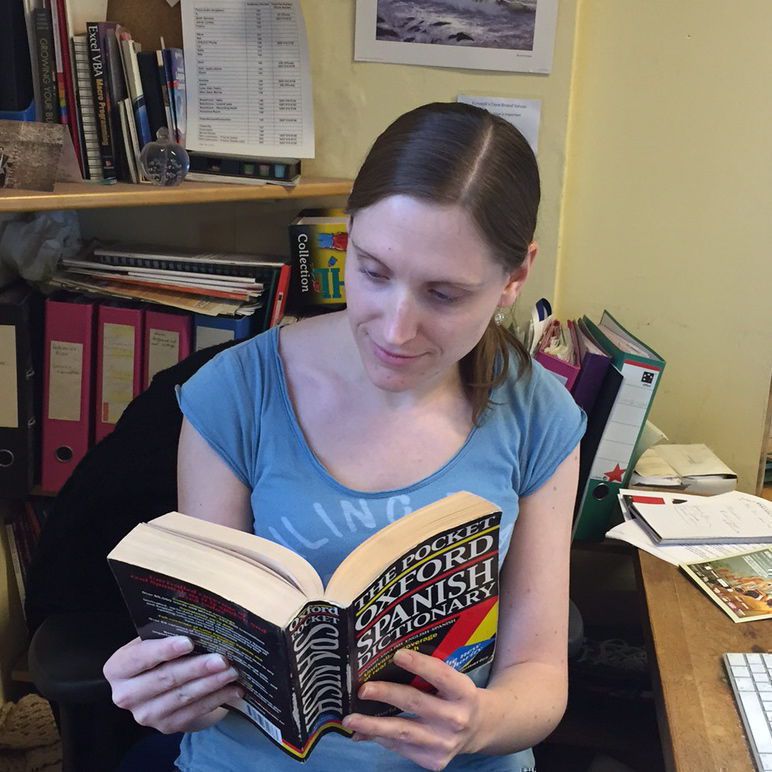

The other day, in a moment of idle curiosity, I took an online Spanish test. And it went rather well; when I finished, I was told that I was 87% fluent.

This is very funny, because – to my shame – I haven’t spoken Spanish properly for years. And although the test proved that everything I learnt at school and university is still there in my head, I know the next time I do try and have a conversation, I’ll struggle initially to remember the right words and how to construct sentences correctly. And there’ll definitely be a lot of ‘um’ and ‘er’.

Defining yourself as ‘fluent’ or ‘not’ seems like a simple enough task. Personally, I’d define fluency as the moment you’re able to have a conversation in another language without hesitation, just as you would in your own native language.

But is that setting too high a standard for myself? Surely what I’ve just described is one step on – what we would call native level?

So, I asked a few other EuroTalkers how they define fluency. A couple of responses were very much like mine:

“When you’re able to have a conversation (spoken or written) without making mistakes, without having to pause to think about words and grammar and without referring to a dictionary or other ‘cheat-sheets’. Be able to use the more complex features of a language with ease (e.g. conditionals, obscure tenses).”

“Speaking another language without having to think about it.”

While a couple were willing to be a bit more flexible:

“When you have enough of the language to get through a visit to the country, you can understand a local and they can understand you back when you speak their language.”

“I think minor mistakes are permitted as long as the other one understands you.”

And another one came at the question from an angle I’d never considered:

“You’re able to have any conversation about general knowledge, not specific fields like medicine, for example.”

But there was one thing all the answers seemed to have in common: the key to fluency is confidence, whether you know all the words or not. And that’s why I can’t think of myself as 87% fluent in Spanish; yes, I understand how the subjunctive works, and perhaps I’d even say that I can read the language fluently – but that doesn’t mean I can confidently have a conversation with someone about the weather.

What do you think ‘fluent’ means? Are you fluent in any other languages?

Liz

Just how bad was Mark Zuckerberg’s Mandarin anyway?

A couple of weeks ago, Mark Zuckerberg shocked the world by taking part in a 30-minute Q&A session in Mandarin Chinese. And we were all super impressed.

It was obvious, even to a non-Mandarin speaker, that he wasn’t completely fluent, but he managed to keep going for almost the full half hour, and his audience at Tsinghua University in Beijing seemed to enjoy his jokes, and his efforts at speaking their language. And it all sounded pretty good to me.

Which just goes to show how much I know. Not too long after the video appeared online, Isaac Stone Fish, Asia Editor at Foreign Policy Magazine, gave his assessment of the Facebook CEO’s efforts: ‘in a word, terrible’. The headline of the piece was, ‘Mark Zuckerberg speaks Mandarin like a seven-year-old’. Ouch.

Since the article was published, people have been jumping into the debate left, right and centre with their own opinions on how he did. James Fallows, writing for The Atlantic, said that Zuckerberg spoke Mandarin ‘as if he had never heard of the all-important Chinese concept of tones’, whereas Mark Rowswell, a Canadian comic who’s fluent in Mandarin and famous throughout China, took to Twitter with a more balanced view.

To clarify, Mark Zuckerberg's Chinese isn't very good. He's incredibly fluent for a Fortune 500 CEO. Which angle do you choose to take?

— 大山 Dashan (@akaDashan) November 1, 2014

Meanwhile, Kevin Slaten, program coordinator at China Labor Watch, was more concerned about the message being given out by Stone Fish’s article. Mark Zuckerberg, after all, is used to bad press and is hardly likely to be put off by a few negative comments. But Slaten looks at the bigger picture: ‘What is Stone Fish, a “China expert”, telling these students of Chinese when he is tearing down a notable person for speaking non-standard Mandarin? He’s telling them, “you’ll be laughed at”’.

Personally, I don’t know how good Zuckerberg’s Mandarin was. It sounded good to me, and as someone who really struggles with nerves when speaking another language, especially to native speakers, I’m pretty much in awe that he had the confidence to give it a go, particularly since it was a Q&A session, not a prepared presentation. (Not that I think Mark Zuckerberg is particularly short on confidence, but you know what I mean.) Had the audience sat there shaking their heads, looking confused or angry, things might be different, but they clearly appreciated the effort he’d put in, so who am I to judge?

Making mistakes is part of learning a language. Everyone has a funny or embarrassing story about a time they used the wrong word, or – in the case of languages like Mandarin or Thai – got the tone slightly incorrect and ended up saying something completely different than what they intended. There’s no shame in it, and in my experience, people appreciate the effort made. Mark Zuckerberg didn’t have to do that interview in Mandarin. He could have done what was expected of him and spoken English. And maybe he messed it up, but I bet everyone in that audience went home with a smile on their face (even if it was more from amusement than anything else).

Isaac Stone Fish has since responded to the criticism of his criticism, stating that his issue was with the media outlets who described Zuckerberg’s Mandarin as fluent, when it wasn’t. Which is fair enough, and maybe some of his comments were taken out of context, but I think the main point stands.

There’s a quote by Abraham Lincoln: ‘Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak out and remove all doubt.’ I don’t agree, at least not in the context of language learning. I say speak out, remove all doubt, have a laugh about it, and then learn from the experience. Otherwise, how will you ever get any better?

So let’s give Mark Zuckerberg – and every other language learner on the planet – a break.

What did you make of the Facebook boss’s Mandarin? Have you ever surprised people by speaking their language?

Liz