How the scripts hit the streets

I quite like the way that the iconography of foreign languages and exotic scripts happily manages to pervade our popular culture. It’s all over the place – it’s on the streets, we wear it , we eat it, we watch it and much of the time we have a laugh. And we have a bunch of rather clever advertisers and retail brands to thank for it.

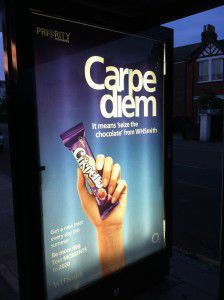

Shall we begin with a little Latin? If you’ve been watching O2’s hilarious ‘be more dog‘ ads or sat at one of the 10,000,000 bus stops in London you will now know that the timeless rallying cry Carpe Diem has hit the streets. And, once you’ve had a hoot at the cat-that-turns-into-a-dog footage, you’ll have learnt that Carpe Diem means… ‘Grab the Frisbee’. I somehow think that Horace, who wrote the words c. 50 BC, would have agreed it was not too bad a translation for 2013 AD. I love the idea that some Latin is out there and available to all, a call to make the most of it, to seize the day!

So make a noise for VCCP, the agency who dreamt the whole campaign up; as an ex JWT exec myself , I am impressed.

And now to Japanese. How many of you think that the Superdry clothing brand, with its cool hoodies, tops and t-shirts plastered with Kanji and Hiragana, comes from Japan? Sorry to disappoint, but Superdry has its origins not in an office in downtown Tokyo, but in a market stall in Cheltenham, where a guy called Julian Dunkerton began selling branded clothing and later had the idea to use Japanese script on his clothing. And the rest, as they say, is history – Julian is now the Chief Exec of one of the UK’s top clothing companies.

It may be reassuring to know that although the company itself is no more Japanese than a benko box from Pret, I am told that the writing is not gobbledygook but does actually mean something: which I am sure is neither unprintable, nor deeply philosophical, but I rather like the idea of millions of people in London walking around with Japanese on their backs – and their fronts.

Of course I am not attempting to connect any of this to a serious attempt to learn a language – though the thought of people queuing up to take degrees in Classics and Japanese is a most appealing one.

However, I’m sure that most of us have at least some interest in the world around us, and iconic branding and imagery can often excite our curiosity, make us think a bit and have us see the world in a slightly new and refreshing way.

Steve

(Photo courtesy of Superdry.com)

If at first you don’t succeed…

Gloria’s post today is about her work on the EuroTalk roof garden, which is a lovely place for us to enjoy in the summer sunshine. Getting it that way hasn’t been easy, but the end result shows that sometimes it’s worth persevering. The same could be said for learning a language!

When I was first handed responsibility for looking after the roof garden at EuroTalk I felt quite smug. Easy – or so I thought! And a good reason (or excuse?) for removing myself from the computer screen quite often. I have a large garden at home, so I already have a lot of experience in planting, pruning, weeding and watering etc. What’s more – I know it’s an ongoing task for at least nine months of the year, so I expected a lot of hard, back-breaking work in the open air. I wasn’t wrong!

What I didn’t bargain for was the changing face of EuroTalk.

Last summer (2012) I had a beautiful display of colours blending up on the roof. My favourites are the pinks and mauves, so I’d planted a whole lot of flowers in these colours. By June the roof garden was looking really healthy and beautiful and I felt that all my backaches had been worth it. Then it happened!

Last summer (2012) I had a beautiful display of colours blending up on the roof. My favourites are the pinks and mauves, so I’d planted a whole lot of flowers in these colours. By June the roof garden was looking really healthy and beautiful and I felt that all my backaches had been worth it. Then it happened!

In July the builders moved in. They erected scaffolding on the terrace and moved a lot of the pots to safer places while they worked on building a new room and putting in a panoramic window which formed the entire exterior wall of this extension. But this took time – nine months, to be exact. I could have had a baby in that length of time (well I couldn’t, but one of our younger staff did!)

The two canvas sails, which had created shade for anyone sitting at the huge wooden table, were removed and allowed to hang up against a wall, thus preventing both light and rain water from reaching a number of the troughs and pots throughout the autumn and winter. Builders rubble appeared out of nowhere – bricks, cement, wood, plastic bags and sacks etc. – you name it and it appeared on our lovely roof terrace. I sat and cried, and vowed to myself that someone else could sort it all out once the building work was finished. I’d had enough. I felt totally disillusioned at all my hard work being destroyed.

Although I went on to the roof garden several times during those dark months, I wasn’t able to do much other than put some water on the dried out pots and cross my fingers!

Then finally, in March 2013 the building work was completed. On the third attempt, the panoramic window was finally fitted satisfactorily and the scaffolding eventually disappeared. The rubble was cleared away and all the pots were put back into place. The builders did a very good job of cleaning the roof garden and the artificial turf began to look like real grass once more. Even the cigarette ends disappeared.

Then began the task of resurrection. A number of visits to the garden centre worked wonders. Then the automatic watering system caused a number of problems. Not all pots had feeds off the main, so this had to be sorted out. Once we had additional bits and pieces, again I thought it was finished. Not so. The older bits didn’t like working with the newer ones so another visit to the garden centre was required. With help from two of my colleagues (Alan and Steve) it is now working correctly. Fingers crossed again!

I split and transferred the crocosmia so that both cauldrons now contain orange crocosmia and a potentilla – one yellow and one white. The main pots and troughs are back up and in full flower, mainly pinks and mauves of course, but with a few other colours added for variety. I’d managed to salvage the lavenders, but it took a lot of T.L.C. and I’m now happy once more with the result – a verdant, lush, colourful display.

I split and transferred the crocosmia so that both cauldrons now contain orange crocosmia and a potentilla – one yellow and one white. The main pots and troughs are back up and in full flower, mainly pinks and mauves of course, but with a few other colours added for variety. I’d managed to salvage the lavenders, but it took a lot of T.L.C. and I’m now happy once more with the result – a verdant, lush, colourful display.

With the constantly changing colours and differing amounts of foliage as the year progresses, I see it as a kaleidoscope of never-ending challenges. And I’m currently rooting some chocolate mint on my desk to replace the one that shrivelled from lack of water. Yipppeeee – it’s working.

But I’m begging our bosses, please don’t plan to do any more extensions. My back and my temper can’t take it…….

Gloria

Lost in translation: making sense of maths

Reading Nat’s post about all the fascinating linguistic differences and difficulties that she and her translators experienced when translating the new uTalk app, I was reminded of some of the similar issues we’ve had in localising the maths apps. What seems totally normal to a three-year-old in the UK might not be all that familiar to a kid in Malawi, for a start! Not to mention the fact that (unfortunately for us English speakers), not all languages follow our grammar rules. Here are a few of the cultural and language localisation issues we’ve come across recently…

In Swedish, there were a couple of interesting language differences, for example: you cannot use the same word for ‘height’ in Swedish for an object such as a house as for a person (Välj det Längsta barnet – choose the tallest child, but Välj det högsta trädet – the tallest tree), whereas in English we can say short or tall regardless of the object.

In Swedish, there were a couple of interesting language differences, for example: you cannot use the same word for ‘height’ in Swedish for an object such as a house as for a person (Välj det Längsta barnet – choose the tallest child, but Välj det högsta trädet – the tallest tree), whereas in English we can say short or tall regardless of the object.

In Malawi, some of the ‘everyday’ objects featured in the apps probably seemed more than a little strange. In fact, Chichewa is strongly based on words for things that people see and encounter in daily life. Our translator had to get a bit creative and come up with ‘equivalent’ names for objects such as a robot (a doll in the Chichewa version), a turnip (a potato in the app), a dragon (she had to use a description meaning ‘a fierce animal’) or a fridge (replaced by a cupboard). There are also many more ‘technical’ words which don’t exist in traditional Chichewa, such as shapes. These are therefore normally given English names with a slight Chichewa accent (sikweya, trayango, rekitango and so on).

This is quite similar in Wolof: many items simply do not have a name in Wolof, or the words are unfamilar to most young people. Many items are therefore named in French instead, such as animals (giraffe), shapes (cercle) or fruits (banane). Above about 10, Wolof-speakers also tend to revert to French numbers instead of the more complex Wolof system (similar to the Chichewa – 5 and 1, 5 and 2…).

As with the uTalk app, Polish proved an especially problematic language for us too. One of the biggest issues was that in Polish the word for ‘you’ is dependent on gender. The translator mainly dealt with this by saying ‘we’ (e.g. Nauczyliśmy się/robiliśmy – we learned/were learning how to…), rather than addressing the child playing the app as male or female. It is also not usual to use prepositions such as ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ when describing the location of an object. e.g. instead of saying ‘the book is outside the cupboard’, Poles would normally say ‘the book is not in the cupboard’. Similarly to many other languages, some of the objects were also not very familiar: a cricket bat is not a well-known object, so it was translated as kijek – a little bat, and mangoes were translated as owoce – a fruit, as mangoes are not a ‘usual’ fruit in Poland – the same was the case with the Hungarian app, where we translated mango as gyumolc – also a generic word for fruit.

As with the uTalk app, Polish proved an especially problematic language for us too. One of the biggest issues was that in Polish the word for ‘you’ is dependent on gender. The translator mainly dealt with this by saying ‘we’ (e.g. Nauczyliśmy się/robiliśmy – we learned/were learning how to…), rather than addressing the child playing the app as male or female. It is also not usual to use prepositions such as ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ when describing the location of an object. e.g. instead of saying ‘the book is outside the cupboard’, Poles would normally say ‘the book is not in the cupboard’. Similarly to many other languages, some of the objects were also not very familiar: a cricket bat is not a well-known object, so it was translated as kijek – a little bat, and mangoes were translated as owoce – a fruit, as mangoes are not a ‘usual’ fruit in Poland – the same was the case with the Hungarian app, where we translated mango as gyumolc – also a generic word for fruit.

In Portuguese, there is no real way to distinguish between ‘more’ and ‘most’ or ‘less’ and ‘least’. Mais means both more and most, and menos less/least/fewer/fewest. This is also the case in Welsh: ‘bigger’ and ‘biggest’ translate to mwy and mwyaf respectively, but ‘more’ and ‘most’ also translate to mwy and mwyaf. The same goes for ‘smaller’/’smallest’ and ‘less’/’least’ (llai, lleiaf). On the other hand, there are different words for top and bottom shelves. Generally ‘top’ and ‘bottom’ are top and gwaelod but ‘top shelf’ and ‘bottom shelf’ are silff uchaf and silff usaf.

I was also intrigued to find out that in Amharic (an African language spoken in Ethiopia), they have a completely different system for telling the time: ‘1 o’clock’ does not mean lunch time, it in fact means ‘the first hour of the day’, i.e. when the sun comes up, and the rest of the day is counted from there. In fact, “Telling the time’ has been one of the hardest topics to localise, as our ideas of what happens at what time are not exactly international. Our French translator not only found the idea of eating a boiled egg for breakfast rather funny, but also pointed out that schools finish at 5 in France, not 3 as in the app, and a child would eat dinner at 7 or 8, not at 5 or 6! In Spain this is even funnier, as Spanish children regularly eat their dinner at 9 p.m., and go to sleep at 10 p.m. or perhaps later at the weekend or on holiday.

These are just a few of the language and cultural issues we’ve encountered on the maths translation project, and there are sure to be more! We have 10+ new languages ready to be released, and many more in the pipeline, so watch this space!

Alex

The maths apps are available from the App Store: Maths, age 3-5 and Maths, age 4-6.

The maths apps are available from the App Store: Maths, age 3-5 and Maths, age 4-6.

And also now available (in English only for the time being), Counting to 10, our first maths practice app, is on sale in the iTunes App Store for iPhone, iPod touch and iPad, and Google Play, for Android devices.

Do you know who you’re talking to?

Our post today is by Izabella Klein, who’s been working with us to translate our maths apps into Brazilian Portuguese. Izabella’s post is about the importance of getting to know your target audience as a translator, and understanding more than just the words used.

Have you ever read an article, document or webpage in your own language that you can clearly see has been translated from another language? The sentences don’t really make sense, or have wordings that are not commonly used where you come from or where it’s been published. Do you get bored or lose interest because of this? I would say most likely yes!

There are two main reasons for this. One, it has been translated by a translation device. Or two, it has been translated by real people, but they were not careful to take into consideration the target public – you.

Reason number one I will disregard, because I strongly do not recommend this option for translation. But let’s go a bit deeper into reason number two, and look at why many translations are not handled carefully, to catch the attention of the readers, or even just make them understandable.

Let’s take the English language as an example. How many different countries in the world speak English as a first language? USA, England, Australia, some of Canada, some of Africa and even more. But, although it is all English, each one of them has a particular way of communicating; they use different words, they have different local parlance, slang and so on. Spanish is another language spoken worldwide as a first language; take Spain, Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Venezuela and Ecuador for example. And even if we talk specifically about Spain, they still have other variations, such as Catalan and Galician.

So, even if someone is fluent in a specific language, that doesn’t mean they are capable of translating perfectly to that language in any place in the world where this is the native language. You must understand the minimum of their culture, their slang, and how they usually communicate something that you are interested in communicating to them.

I’ll take myself as an example. I’ve been working for Japanese people for the last couple of years as a linguist, using Portuguese and English as source and target languages. In the beginning it was a hard task. Much of what was said or written to me was difficult to understand: their awkward accent, the different words they used (words that are in the dictionary, but I’d never really heard people saying them on a daily basis), or incomplete sentences. So I had to get used to their weird English sentences, sometimes just random words that I had to put together like a puzzle and figure out the missing words. But, in the end, it was just a matter of adapting to their culture, or to JapanEnglish as I call it. Now, I feel 100% confident while working with them. I had to spend a year studing their different habits, and basically dig a way into making myself understandable in their language, in this case JapanEnglish.

You might say JapanEnglish is not really a language, but I argue that it is. It’s just a mixture of Japanese and English, the same way Catalan is a mixture of Spanish and French; and Galician a mixture of Spanish and Portuguese. The only difference is JapanEnglish is not an official language. My point here is that it’s important to realise why you must get to know your target public as deeply as possible, so that your translation work will be accurate.

I can also take my internship at EuroTalk as a second example of my work experience. I worked in app localisation, focused on teaching maths to very young children. Some might say it must have been an easy task. But actually it was not that easy. Children are different from adults, they use different vocabulary and they can easily get distracted. Plus, you can’t use a completely different vocabulary than teachers use at school, because the main idea is to reinforce what they will learn or are already learning at school; otherwise you might just confuse them, which will mean unhappy children and parents.

I know that for most linguists time is money, as it is for most people, but a piece of advice from what I have learned during my career is, take some time and effort to study your market. I believe that if you do, your chances of boosting your career are greater.

Izabella

The benefits of exposing younger children to multiple languages

Today we have a guest post by Stephen Thomas, on behalf of Pearson PTE, on why it’s important to expose children to other languages at a young age.

Why expose children to other languages?

Communication is fundamentally part of what makes us unique organisms on earth. The way that we have developed language to exchange concepts, ideas, narratives and so on with sounds that are culturally recognised to the degree of complexity we have, is distinctive and unmatched by any other organism.

Clearly then, learning a language reaps obvious benefits: we can learn and understand new things with ease, retain ideas throughout decades, make each other laugh and cry, discuss, debate and develop the most fundamental questions of philosophy – all through using just one language. So aside from the want or need to communicate with speakers of a different language, is there any benefit of being bilingual or raising children that are bilingual? Well, Pearson PTE spoke with Dr Catriona Morrison, senior lecturer in psychology at The University of Leeds who advised that there is evidence to support the notion that merely exposing children under the age of five to other languages has benefits, regardless of whether or not they become bilingual.

Between the age of 3 and 6 is a vital stage of childhood in terms of language learning and development. The malleable mind of a child

at this age is like a sponge and Dr Morrison advises that “after the age of five, it is highly unlikely to acquire the mother tongue of a language if it is not yet already acquired”. Although in later childhood or adult life we may learn a new language, we can be sure that we do not learn it with anything like the same ease that we would as a child. After this crucial point in child development there begins a change in the human brain that effectively shuts down the ability to ‘naturally’ learn language. Of course that doesn’t mean you can’t learn a language in adulthood, but if you have, I’m sure you will agree that it is much more difficult in contrast to a truly bilingual person (who learned two languages before this crucial stage) whereby the two languages are seamlessly managed within the brain as though they were one.

Beyond the communicative advantages, research suggests that bilingual children have better capacities for storytelling and interpretation. The processing of information seems to happen at a deeper level and they will think through and into the story more. So for example, statistically if we were to take a group of monolingual children and a group of bilingual children and tell them a story, when we ask them to recount the narrative and characters, the bilingual children will show evidence of deeper understanding and a higher level of information processing.

Furthermore, Dr Morrison suggested that bilingualism seems to act as a preventative mechanism against the onset of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. Although it will not create immunity and one may still fall to the condition, statistically if it is going to happen it will happen later in life, when compared to monolingual sufferers. In layman’s terms this could be because one is using more of the brain when accessing two or more languages and thus the brain is more active, and an active mind is a healthy mind.

How can we help children to discover languages?

So if you are a monolingual parent and you see the benefits of bilingualism in younger children, how should you go about helping your child? Realistically, a child of monolingual parents isn’t going to become bilingual, even with partial immersion in other languages through accessing foreign television radio or sending them to a nursery that caters for multiple languages. This is why Dr Morrison agrees that it is such a tragedy that the UK’s schooling system doesn’t introduce children to other languages as it is at this vital time of youth that we have the change to expand their minds in a way that isn’t possible at any other stage of life.

However, this doesn’t mean that the exposure is pointless or irrelevant: “I have a lot of faith in the idea that the more languages a child is exposed to, the better,” says Dr Morrison. Part of what makes language learning hard is that a new language draws on an entirely alien phonemic inventory to what we are used to hearing. When we try to listen to and learn these sounds, our brain simply isn’t accustomed to hearing them. So there is definitely a benefit for parents endeavouring to expose children to these sounds that they would otherwise be starved of and therefore selectively excluded from the brain; absolutely do allow your children to watch foreign TV shows or listen to internet radio form other countries and if possible encourage human interaction with your child and other language speakers. This will only help and bolster their learning and development.

Stephen Thomas

If you’d like your children to start learning a language, why not try our Vocabulary Builder program? With its colourful characters and fun games, it’s a great start for young learners – and it’s available in over 100 languages.