French – champion of the language learning world?

I remember the moment when we knew we were officially grown up in primary school – during French lessons with the headmaster.

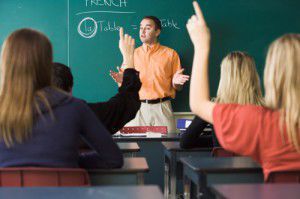

MFL lessons are the norm nowadays but back in my time, French lessons were a weekly highlight, as they meant me and about a dozen classmates spent half an hour learning something the rest of the school did not already know.

As I moved onto secondary school, languages were eventually deemed ‘uncool’ and those who took French or Spanish past GCSE – myself included – were thought to be insane by their peers.

When I think about it, only French got a shoo-in at primary school. Spanish was introduced in the first year of secondary school but even then, all efforts were concentrated on learning and teaching French.

No-one seemed to care about German or Italian and everyone thought Mandarin was a fruit.

This makes me wonder – when did French become the ‘go-to’ foreign language at school?

This makes me wonder – when did French become the ‘go-to’ foreign language at school?

Learning French is a current requirement in UK primary schools and the possibilities of school trips, exchanges and overseas partnerships are endless, but knowing how to speak it may not be as impressive as learning more obscure languages such as Swedish, Polish or Japanese.

The number of people learning a language nowadays relies on how influential it is in popular culture – just look at how many people have started to learn Na’vi, just because it was featured in James Cameron’s 2009 epic Avatar – and this can only be aimed at the younger generation, when ‘cool’ is key.

This is the aim of our annual language competition for primary schools, the Junior Language Challenge. Parents have commented that the competition has fuelled their children’s passion for learning new languages and has inspired them to take up different ones as options for GCSE.

I am hopeful that more unusual languages will be featured in the National Curriculum, but unless Justin Bieber turns around and starts learning Mandarin, whether pre-teens take language learning to the next step is debatable.

Where do you think today’s language learning is going? Where can there be room for improvement? And ask yourselves, in ten years or so, will French reign supreme or can Spanish or Mandarin take the crown as Most Popular Foreign Language to Learn at Primary School?

Katie

Sorry Mickey! Dedicated Ben chooses JLC over Disneyworld

Nine year old Ben Fawcett will be cutting short his family holiday in Disneyworld to take part in this month’s Junior Language Challenge final.

Ben, who is the first pupil from Oakwood School near Chichester to get through to the final, had been due to be in Florida when the final of EuroTalk’s JLC takes place on October 21st.

His mum, Anna, says: “The timing couldn’t have been worse for us. We’re taking the children to Disneyworld for two weeks but Ben and I are only going for one week because the final is in the middle of our planned holiday.

“He’s disappointed but we gave him the choice and he said, ‘No Mummy, I’ve come this far – I want to do it,’ and I’m happy to fly back with him. But the timing couldn’t have been worse. We arrive back the day before the competition so he’ll probably be jet-lagged…”

Holiday plans apart, entering the competition has been a good thing for the Fawcetts.

Anna adds: “Children from Oakwood have made it through to the semi-finals before but not to the finals so Ben’s as proud as a peacock! It’s been really good for his confidence not just with languages but generally. He’s thoroughly enjoyed the competition and I’ve hardly had to remind him to look at the games.”

Having picked up some of the basics of Portuguese and Kazakh in the first two rounds of the competition, Ben is now one of around 40 finalists trying to get to grips with the last JLC language, Luganda.

Anna adds: “I’m obviously extremely proud of him but it’s completely nerve-wracking as well!”

We’re looking forward to seeing Ben and Anna at the final, which will be held at the Language Show next Friday.

Ben’s even made the local paper!

Are there any other semi-finalists out there who’d like to share their JLC story?

To dub or not to dub?

As a British-born Chinese citizen, I adore old Hong-Kong martial arts films. By the time Jackie Chan had made his Hollywood debut, I had seen a number of his critically acclaimed films such as Project A, Wheels on Meals (set and filmed in Barcelona) and Armour of God (where he almost died after a stunt went wrong).

One particular film that stood out was City Hunter, where Jackie Chan plays a bumbling detective caught in the middle of a raid on a cruise ship. The film was quite special as it featured Eastern and Western martial artists with speaking parts – something that I had rarely seen at the time.

I first watched it with all the dialogue in English (even that of the Asian actors) when I was around 10 years old and found it hilarious, but I watched it again several years later only to find all the dialogue was in Chinese, and I didn’t find it so funny. There was a time in the 1980s when martial art films became almost ‘cultish’ with TV audiences, particularly in America. The reason? Whenever they were shown on TV – usually on a weekend when kids were home and could mimic the moves – you had a really bad dialogue (loosely translated from the original script) and terrible lip sync.

Animated films are fortunate enough to not be so heavily affected by dubbing, but when you compare a dubbed live-action with one in its original language, you have to wonder if dubbing is really necessary. Sure, the inclusion of English in any media will make it more accessible than leaving it in languages such as Arabic, Chinese or Spanish, but I would like the idea of all the characters speaking in their own language and providing subtitles where necessary. A colleague pointed out that Inglourious Basterds by Quentin Tarantino is an example of this and it is this feature that explains why it is one of my current-favourite films. All the characters speak their native language or speak the language relevant to the scene with subtitles appearing only when they’re needed.

Dubbing allows the audience to hear a piece of dialogue in a way that is culturally relevant to them and it’s often seen as an alternative to subtitling because the idea of reading during a film can put people off. But this also robs the film of something that’s significant to the nationality of the speaker, lessening the impact of any colloquial phrase.

Are you pro-dubbing or against it? Do you see the need to read subtitling?

Katie

What’s the hardest language to learn?

I remember the first day of my Hispanic Studies degree, when our head of department brought us all down to earth by reminding us that Spanish is one of the easiest languages to learn. Having all worked pretty hard to get there, we were quite offended, but looking back now, I have to admit he may have been right… Spanish follows relatively simple grammatical rules, and once you know the different sounds, you can look at any word, and even if you’ve never seen it before you’ll know how to pronounce it. Of course there are areas of difficulty, like the age-old ‘ser or estar’ debate and (every linguist’s favourite) the subjunctive, but on the whole it isn’t a nightmare to get to grips with.

So that got me thinking: what is the hardest language to learn? Obvious answers that spring to mind are languages like Arabic, Mandarin, Cantonese and Japanese, which use a completely different writing system to English and, in the case of the Chinese languages, rely heavily on tone of voice. Changing the way you say a word even fractionally can completely change its meaning – which makes learning the language seem pretty daunting.

Other languages that I’ve been told are really difficult to learn include Finnish and Hungarian, in this case because of their complicated grammar systems.

Of course this is all from an English speaker’s point of view. If I’d been brought up speaking another language then my ideas about which are most difficult would probably be totally different. I’m sure I’d find English quite hard if I weren’t a native speaker.

What do you think? Have you ever learnt a language that was particularly challenging?

Liz

Is it OK to be Monolingual?

When England’s GCSE results came out at the end of August the British press were quick to report on the declining numbers of students taking the qualification in a foreign language: 12% fewer students than in 2010 sat the exam, and this is part of a continuing downward trend over the last few years. The vast majority took their GCSE in French, followed at some distance by Spanish and then German. Even the modest numbers taking Mandarin Chinese and Arabic have tailed off.

So, does this mean that we are well and truly on the road to become a nation of monolinguals, at ease communicating with the world in English, and more than happy to leave our dirty work to translators, interpreters and other specialists in the field? And does it matter?

A reason many UK experts state for learning a foreign language – the utilitarian one – suggests that having a language is good for business. However, I doubt that this has really had much of a detrimental effect on the bottom line of UK plc over the years and it is certainly not a motivating factor in persuading a 13 year old to learn Spanish. Although many employers prize a language qualification, the fact is that most jobs don’t require one.

So what about the appreciation of a country’s culture? Do you really need a knowledge of Italian to appreciate Renaissance art? Or of Chinese to understand the triumphs of the Ming Dynasty? It is entirely possible to promote awareness of these subjects in English.

I do think there are powerful reasons why young people should learn a language and the factors of interest to teenagers – the social ones, the sheer fun of it, the intrinsic joy of reaching into another world – are well set out at www.whystudylanguages.ac.uk. The question is: should all children be forced to take a language up to the age of 16?

Perhaps not all of them, if it depends on our current examination system and the knowledge it equips them with. That said, there are changes afoot in the secondary syllabus, and alternative language programs are also being pioneered in the UK. One of these works like music, on the basis of awarding progress through a step-by-step grades system.

And if formal education fails, many people find ways of acquiring language skills later in life, when they have a clearer idea of what they need to learn and why.

Steve