Something Borrowed: when one language just isn’t enough

After reading Konstantia’s post a few months ago about how many of our everyday words come from Greek, I started to think about where some of our other words came from. You might think that we are the ones influencing everyone else (words such as wifi in French, surfear for surfing the net in Spanish, and a lot of business jargon in German – downloaden, ein Workshop, ein Meeting and so on…), and of course that’s true. Most new inventions (the Internet, computers and related tech such as wifi) are named by Americans, and therefore the English word is often passed along to other cultures and absorbed into their languages. You’ll also find many non-English speakers throwing in English phrases amidst their native tongue. Any other Borgen fans will probably have noticed the way that characters casually use phrases such as ‘on a need to know basis’ whilst otherwise conversing in Danish. Clearly our language, especially in the business, IT and entertainment domains, has a huge global influence.

However, if you look a little further back, you’ll find us doing exactly the same thing. It might seem incredibly cool to Europeans now to use English or merely ‘English-sounding’ words day to day, but we’re just as guilty of language-envy or just pure laziness with French, especially. How to describe that annoying feeling of being sure you’ve already seen or done something? Déjà vu, of course. Not to mention dozens of other words and phrases we all use on a daily or regular basis: laissez faire, enfant terrible, a la carte, a la mode, arte nouveau, en route, faux pas… I could go on for pages. You’d probably struggle to go through a day without using at least one or two obviously French words. It’s almost as if we simply couldn’t be bothered to think of our own words for some of these things, although I also suspect it has a lot to do with our associations with French as chic (another one!) and sexy. This is especially true in the beauty industry, which explains the proliferation of products labelled visage or with names like touche eclat remaining in their original alluring French guise.

However, if you look a little further back, you’ll find us doing exactly the same thing. It might seem incredibly cool to Europeans now to use English or merely ‘English-sounding’ words day to day, but we’re just as guilty of language-envy or just pure laziness with French, especially. How to describe that annoying feeling of being sure you’ve already seen or done something? Déjà vu, of course. Not to mention dozens of other words and phrases we all use on a daily or regular basis: laissez faire, enfant terrible, a la carte, a la mode, arte nouveau, en route, faux pas… I could go on for pages. You’d probably struggle to go through a day without using at least one or two obviously French words. It’s almost as if we simply couldn’t be bothered to think of our own words for some of these things, although I also suspect it has a lot to do with our associations with French as chic (another one!) and sexy. This is especially true in the beauty industry, which explains the proliferation of products labelled visage or with names like touche eclat remaining in their original alluring French guise.

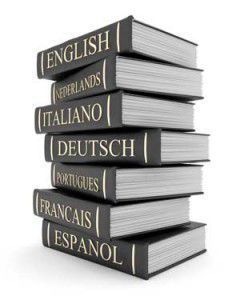

French is the best example, as they are our nearest geographical neighbours, and historically one of our closest political connections, which explains the huge interconnection of our languages. However, as soon as you think about it, there are hundreds of other words that have crept into our parlance from other languages. Words like Zeitgeist and one of my favourites Schadenfreude have come over from German, whilst our food vocabulary owes a lot to Spanish (salsa, jalapeno, tortilla, nacho, paella…) We’re also becoming ever more familiar with words and especially foods from China and Japan. Sushi, sake, kimono, karate, karaoke and so on are everyday words to us, whilst we happily order bok choy, chop suey and chow mein without even thinking about it, not to mention concepts like yen, zen and feng shui. Taekwondo has made its way over from Korea, whilst we’ve taken words like bamboo and paddy from Malay.

This is just a quick look at some of the more obvious ways that our language has spread globally, and how many words we have absorbed from nearby European countries, but also from more distant Asian cultures. We’re such a global country, and it’s strongly reflected in our language. We’d love to hear more examples of English words creeping into other languages or other foreign words you’ve noticed in English, so feel free to leave a comment below!

Alex

Utility versus Beauty

Cristina Mateos is our Catalan intern here at EuroTalk, working on translating and recording our maths apps. In her blog post she explores a reason for learning languages that is often forgotten.

Utility versus Beauty.

Utility: Hammers, zips, kettles, light bulbs, electricity, mobile phones.

Beauty: Handwritten postcards, dawns, coffee smell, lovers looking into each others’ eyes, handknitted scarves.

The world where I live stores useful belongings in closed wardrobes and turns on the radio so as not to listen to the silence around. As a Spanish teacher, I sell my courses by reminding these ‘utility users’ of the fact that 500 million people speak Spanish around the world. It is therefore extremely practical to be able to communicate in this language and to display that knowledge (especially if it comes with an official certificate) on one’s résumé. And I really believe that… and I am more than pleased with zips and light bulbs. But I feel sorry for the dawns. I feel sorry for the dawns and for language learners turning into language users. I would like my students to be able to ask for directions in Sevilla, complete a business deal with a big enterprise in Buenos Aires or get a train ticket in any Spanish train station, but I also want them to be fascinated by the beauty of my language.

The world where I live stores useful belongings in closed wardrobes and turns on the radio so as not to listen to the silence around. As a Spanish teacher, I sell my courses by reminding these ‘utility users’ of the fact that 500 million people speak Spanish around the world. It is therefore extremely practical to be able to communicate in this language and to display that knowledge (especially if it comes with an official certificate) on one’s résumé. And I really believe that… and I am more than pleased with zips and light bulbs. But I feel sorry for the dawns. I feel sorry for the dawns and for language learners turning into language users. I would like my students to be able to ask for directions in Sevilla, complete a business deal with a big enterprise in Buenos Aires or get a train ticket in any Spanish train station, but I also want them to be fascinated by the beauty of my language.

Los rinocerontes no pueden leer. This is probably the most pointless sentence ever, unless you meet a woman crying in disappointment because a rhino isn’t answering her love letters, and you find it necessary to clarify for her that rhinos cannot read. But the sentence itself: its sonority, the combination of the ‘e’ letters together, the way grammar is used in it, the choice of the masculine gender instead of the feminine… it moves language away from usefulness and places it closer to poetry. Don’t you find it amazing how it’s possible to play with a language and build nonsense sentences? Making up words – and this is something, as language learners, that we constantly do when trying to refer to concepts we don’t know the name for – just by using common lexical rules? (Like The mugness of a morning, or This dog is so killable when it starts barking in the middle of the night.) Have you ever fallen in love with a word in your own language just because of the way it sounds, as if it were a piece of music with no meaning at all apart from the feelings it causes for you? If not, I can suggest one in English that I love: wibble. And I can provide one in Spanish too… barítono. Beautiful as a handknitted scarf.

Let me come back to the point. As a Catalan speaker, I feel also sorry for my second first language. Catalan has been left apart so many times in the name of utility that too often I need to make a real effort to keep on using it. I have been told that Spanish is more practical. More and more parents in non-English speaking countries choose a school for their children taking into account nothing but the number of hours their children are going to be taught English, because English (and now probably also Chinese?) is the Future.

Then, in Utility’s name… we can close small shops and open more and more supermarkets. We can burn poetry books and publish more instruction manuals. We can forget about nice roasts and pies and cheesecakes, and ingest vitamins and protein pills every morning.

But if, like me, you feel sorry for the dawns, then learn another language.

Cristina

The Art of Interpreting

Kana Tsumoto has just finished her internship with us, translating and recording our maths app into Japanese. In this post, she explains why she’s excited about her chosen career in interpreting.

The other night when I stayed at a youth hostel, I had an uncomfortable conversation with one of my roommates. I told her how I just finished a university course in Translation and Interpreting and how I am about to embark on my new career as a translator/interpreter. Then, in a not so roundabout way, she started to criticise my future profession, describing it as a boring task; merely repeating what has already been stated but in a different language! I shouldn’t have let her get on my nerves, but she did. I endured this for three days, and on the fourth she left. The initial joy felt at her absence soon descended into shame. It suddenly dawned on me that I had been a massive coward! I had failed to stand up for my profession, failed to defend it against a misinformed foe! Since then, I have been composing in my mind a grand speech on how wonderful translating and interpreting is. I would like to take this opportunity to share this speech, and dedicate it to my roommate in 303.

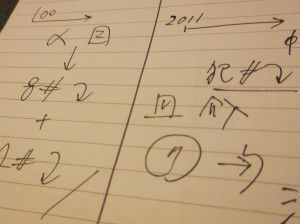

Interpreting is, in fact, very exciting and very demanding! You definitely do need an extremely good command of the language you are interpreting into/from, but surprisingly more important are other skills including for example research management skills, communication skills, a sense of conciseness and even drawing skills! I was flabbergasted myself by this when I first started the course. Let me go through some of these skills with you.

Interpreting is, in fact, very exciting and very demanding! You definitely do need an extremely good command of the language you are interpreting into/from, but surprisingly more important are other skills including for example research management skills, communication skills, a sense of conciseness and even drawing skills! I was flabbergasted myself by this when I first started the course. Let me go through some of these skills with you.

Communicating skills: Interpreting belongs to the service industry. So as a service, being able to communicate with your clients is a vital skill. Interpreters need flexible communication skills to survive in many different environments, such as court rooms and their tense atmosphere, to the bonhomie found at sales talks, or the acute technical details found at academic conferences.

Researching: Interpreters spend a significant amount of time on research. This takes place prior to the actual performance. An hour long session of interpreting can require days, even weeks, of research for it to be successful. Research allows the interpreter to familiarise themselves with the terminology and theories that are going to be employed during a speech or conference. Interpretation without research is in some cases impossible. If you don’t know what is being said then how can you translate?! A good interpreter immerses themselves within their particular field, becoming expert in their chosen subject.

Drawing skills: We interpreters are artists when it comes to taking notes. During consecutive interpreting, we usually make quick notes of the speech. But of course we don’t have much time for writing down stuff, nor can we spend much time looking at the notes when performing; we have to talk to the audience, not to our notes! So we take notes through the medium of drawing, or rather, in symbols! The symbols need to be simple enough to scribble down and meaningful enough to allow us to understand the logical flow and the details in just one glance.

Last but definitely not least…

Sense of conciseness: This, I find most difficult to improve (I’m going to have trouble explaining conciseness concisely, oh dear!… But here I go!). The best translation that suits the context and the intention of the speech may not be the translation you find in the dictionary. A good interpreter never burdens the audience with the task of trying to understand the interpretations; they are like a guide on a cruise liner, taking with them passengers for a seaside tour in the greatest of comfort. A bad interpreter however, forces their passengers to balance out the back of the boat on water skis, whilst showing them the same scenery. Exercising the skills of conciseness in the midst of interpreting is not an easy task, and it comes only through lots and lots of practice. It is an art form, and when it is done right it is beautiful!

As you can see, interpreting can be a very demanding job. It comes with everyday hard work. The process of striving for something and then accomplishing it is definitely exciting. Now put that in your pipe and smoke it, my roommate from the hostel! 😉

Kana

The Trouble with the Title

Today’s post is by our Italian intern, Ambra Calvi, a film fan who’s noticed some interesting translations of movie titles…

One of the main pleasures of learning a new language is getting to that point when you are able to watch a film in that language, and you start to understand bits and pieces. Nowadays, it’s become fairly easy to get hold of foreign titles. In the UK in particular, the range of titles available is very diverse, sustained by a long standing interest in so-called “world cinema”. On top of the usual foreign Oscar contenders every year, you can also catch the latest works of an upcoming Turkish director, or challenge yourself with a Thai action film, or spend the afternoon with a gripping Argentine drama.

However, when a film is made available to international audiences outside the nation where it was made, it has to go through an essential process: the translation of its title. This is just one part of the bigger process of localisation which involves translating and adapting all the dialogues for subtitling or dubbing, but it’s an essential part. The title is the film’s immediate presentation, its way of attracting viewers, giving them a hint of the story and instiling some expectations about the experience they are going to have. Together with the poster, those few words can be crucial for the success of the film.

However, when a film is made available to international audiences outside the nation where it was made, it has to go through an essential process: the translation of its title. This is just one part of the bigger process of localisation which involves translating and adapting all the dialogues for subtitling or dubbing, but it’s an essential part. The title is the film’s immediate presentation, its way of attracting viewers, giving them a hint of the story and instiling some expectations about the experience they are going to have. Together with the poster, those few words can be crucial for the success of the film.

Growing up in Italy and being a film buff from a very early age, this is an issue that I’ve had to deal with quite a few times. At weekends, when choosing which film to watch from the leaflet of my local multiplex, if I didn’t know some films I would naively rely on the way their titles sounded. Unfortunately, this wasn’t always a good idea. I soon realised that somewhere in the mysterious places where the films were prepared for the Italian market, some people were using their creative flair to catastrophic results.

I’ll give you some examples: have you ever seen Crystal Trap? Doesn’t ring a bell? That’s because it’s the title under which Die Hard was released in Italy in the Eighties (as “Trappola di cristallo”). What about The Fleeting Moment? No? Well, that was Dead Poets Society (“L’attimo fuggente”). More recently, you could have seen posters of Bitter Paradise (“Paradiso amaro”), and had it not been for George Clooney sitting on a Hawaiian beach you would have never recognised The Descendants.

After keeping an eye on this worrying trend in the past years, I can now group these frequent translation oddities in recurrent categories:

- Radical changes from the original title, often resulting in a more banal – or just silly – new one: see for example How to Lose Friends and Alienate People, translated as Star System: If You’re Not There You Don’t Exist (“Se non ci sei non esisti”). Even worse, The Back-up Plan, which became Nice to Meet You, I’m a Bit Pregnant (“Piacere, sono un po’ incinta”). Similarly, The Break Up was translated as I Hate You, I Dump You, I… (“Ti odio, ti lascio, ti…”). Sometimes the changes of meaning in the title are completely unnecessary: can anyone explain to me why Beasts of the Southern Wild had to become King of the Wild Land (“Re della terra selvaggia”)?

- An unexplainable tendency to romanticize: the popular The Shawshank Redemption became The Wings of Freedom (“Le ali della libertà”), and The Place Beyond the Pines, the new Ryan Gosling film, will be released as Like a Thunder (“Come un tuono”). More specifically, there seems to be a belief that inserting the word “love” in a title will magically attract millions of people craving for super sentimental stories: following this theory, The Time Traveler’s Wife was translated as A Sudden Love (“Un amore all’improvviso”), and the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line became When Love Burns the Soul (“Quando l’amore brucia l’anima”).

- The real horror happens when translators come up with one bad title, and in the years to come they use a series of variations for other non-related films. This happened with Runaway Bride, with Julia Roberts and Richard Gere, which was translated as If You Run Away I’ll Marry You (“Se scappi ti sposo”), and was then followed by Intolerable Cruelty becoming First I’ll Marry You Then I’ll Ruin You (“Prima ti sposo poi ti rovino). Then the lowest point in this disaster: the dreamy, wonderful Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind was smuggled as If You Leave Me I’ll Erase You (“Se mi lasci ti cancello”), alienating the sympathies of most sensible viewers. A similar fashion started with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre becoming Don’t Open That Door (“Non aprite quella porta”), which generated Don’t Enter that School (“Non entrate in quella scuola”, originally Prom Night) and Don’t Open That Closet (“Non aprite quell’armadio”, which was Monster in the Closet).

There are – unfortunately – hundreds of other examples, but this is enough to show how a bad title translation can completely alter the destiny of a film, consigning some masterpieces to oblivion only because they are mistaken for something completely different, or because they sound like cheap b-movies. While in some cases of films with short, simple titles, keeping the original version can be the best solution, generally speaking Italian distributors should really make an effort and try to come up with creative, honest ideas to maintain the intention of the director. After all, Italy has a great tradition in literary translation, so I don’t see why we shouldn’t do our best when it comes to films as well.

There are – unfortunately – hundreds of other examples, but this is enough to show how a bad title translation can completely alter the destiny of a film, consigning some masterpieces to oblivion only because they are mistaken for something completely different, or because they sound like cheap b-movies. While in some cases of films with short, simple titles, keeping the original version can be the best solution, generally speaking Italian distributors should really make an effort and try to come up with creative, honest ideas to maintain the intention of the director. After all, Italy has a great tradition in literary translation, so I don’t see why we shouldn’t do our best when it comes to films as well.

If anyone has any other examples of strange film title translations, we’d love to hear them!

Ambra