10 reasons to visit… Malawi

Today’s post is by Alex from onebillion. As you may know, onebillion are an organisation set up by Jamie and Andrew from EuroTalk to provide basic maths, reading and English teaching through apps to children in developing countries (and they were recently featured in a BBC Click report). A few weeks ago, the whole onebillion team travelled to the African country of Malawi to expand their project to a new school.

Perhaps Malawi might not seem like an obvious choice for a visit, but here are ten reasons why Alex thinks you should give it a try 🙂

1. ‘Interesting’ foods

I’m not sure if this is a reason to visit Malawi or not, but it is quite interesting to see what some of the locals eat. Typical local cuisine mainly consists of a maize porridge called nsima, which they eat 2-3 times a day, but you can buy great-looking fresh fruits for next to nothing. You can also get international cuisine from some restaurants in Lilongwe or Blantyre (the two major cities). But a particular highlight is seeing the ‘mouse boys’ who sell sun-dried mice on sticks (complete with fur) on the side of the road. For some reason none of us has been brave enough to try one yet. You also have to drink some fresh-ground Malawian coffee – and bring back some beans for the EuroTalk and onebillion offices, of course!

2. Lake Malawi

This is one place you have to see before you die. The most beautiful place I’ve ever been to. You can stay in a simple straw beach hut, see the stars and wake up to the sound of the waves and nothing else. The lake is home to many varieties of fish, alligators and hippos, and we saw dozens of monkeys and other critters all around the lake. Including some rather terrifying new species of bugs. Be careful to check whether it’s safe to swim in the part of the lake you visit, but even if you can’t it’s an amazing place to see some stunning nature.

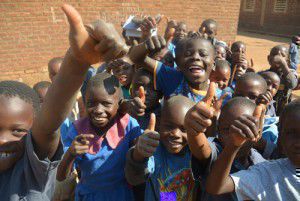

3. Get involved in a voluntary project

onebillion recently returned to Malawi to check up on our progress with delivering tablet-based learning in Biwi school and to expand to another, larger school. We were so excited to see how much progress the children have made with their maths skills. But there are many other organisations working there on things like building schools, digging wells and volunteering as a teacher or healthcare assistant. See Malawi Volunteer Organisation or VSO, for example.

4. See a totally different way of life

Even in Lilongwe, the capital, Malawi is not very developed. You’ll be bumping along mud roads and seeing people walk past with bicycles stacked up with insane quantities of firewood, huge towers of mud bricks being baked dry and barefooted children running around with chickens and goats. Just seeing how people go about their daily lives will give you a new perspective, and chatting to some of the locals and children who have never seen technology such as smartphones or tablets is really worthwhile. Seeing the faces of groups of Malawian children when they first play a maths game on a tablet or seeing our flying ‘drone’ camera was priceless.

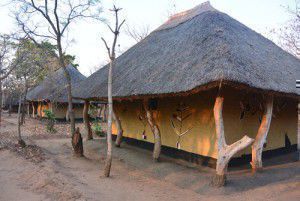

5. Experience life without modern conveniences

You know all those things you take for granted, like running water, drinking water on tap, electric lights, flushing loos, wifi? Maybe try a couple of days in a traditional Malawian-style hut and say goodbye to all of those things for a while! Whilst freezing ‘showers’ from a bucket, candlelight and a few days without Instagram might be hard to get used to – it’s a really interesting experience which makes you appreciate all the home comforts you took for granted before. And you might find you see and experience something new when you’re forced to go without Facebook for a couple of days. Kumbali Village in Lilongwe is the perfect way to experience a back-to-basics stay but with clean water available and clean rooms too.

6. Wildlife!

One of the first things you’ll notice as you take a walk or drive around when you arrive in Malawi is all the different plants and animals that you’ll see everywhere. You can take a safari (the Swahili word for ‘journey’ by the way) or visit one of the country’s incredible national parks, such as Liwonde and Lengwe to see hippos, lions, elephants and more. But you’re likely to spot monkeys, baboons, colourful insects and birds just out and about. Just watch out for chickens, goats and dogs running in front of your car when you’re in one of the villages!

7. Climb Mount Mulanje

I didn’t actually do this when I visited, but Zane and Alan from onebillion did on their visit and said it gave them a really great sense of achievement, as well as an awesome view. Mt Mulanje is 9,849 feet high – quite a climb, but not requiring special equipment or training.

8. Friendly people

We often say this about a place, but in Malawi it really is true! Malawi is called the ‘warm heart of Africa’ and much of this is to do with how warm and friendly people are. They are really genuinely interested to talk to people from other places and happy to share their lives and interests with you in return. They’re also really happy if you manage a couple of simple Chichewa phrases: greet people with ‘moni’ (hello), say ‘zikomo’ (thanks) and ‘chonde’ (please) and you’ll get along fine.

9. Unspoiled landscape and scenery

Depending on the time of year, Malawi is either lush and green or dry and very dusty. However it is always a very impressive country to see, with a variety of different terrains and landscapes, including mountains, lakes and rivers. There are a lot of open spaces and not many tourists, so it’s a great place to see some real and unspoiled nature where commercialism hasn’t taken over yet.

10. The climate!

Ok, since our trips to Malawi are mainly about working on our ‘one billion children’ project we don’t have sooo much time for sunbathing. We’re normally up with the sunrise at 5.30am, in school all day and up charging and configuring tablets, processing data or marking until about 11. But there’s normally some time to relax as well, and sunbathing might also happen (only if our work is done first, honest). You might think of Malawi as extremely hot, but most of the year it is a really nice temperature around 30 degrees and not too humid. Remember your suncream (and insect repellent!) and it really is a great place to soak up some sun.

Alex

Lost in translation: making sense of maths

Reading Nat’s post about all the fascinating linguistic differences and difficulties that she and her translators experienced when translating the new uTalk app, I was reminded of some of the similar issues we’ve had in localising the maths apps. What seems totally normal to a three-year-old in the UK might not be all that familiar to a kid in Malawi, for a start! Not to mention the fact that (unfortunately for us English speakers), not all languages follow our grammar rules. Here are a few of the cultural and language localisation issues we’ve come across recently…

In Swedish, there were a couple of interesting language differences, for example: you cannot use the same word for ‘height’ in Swedish for an object such as a house as for a person (Välj det Längsta barnet – choose the tallest child, but Välj det högsta trädet – the tallest tree), whereas in English we can say short or tall regardless of the object.

In Swedish, there were a couple of interesting language differences, for example: you cannot use the same word for ‘height’ in Swedish for an object such as a house as for a person (Välj det Längsta barnet – choose the tallest child, but Välj det högsta trädet – the tallest tree), whereas in English we can say short or tall regardless of the object.

In Malawi, some of the ‘everyday’ objects featured in the apps probably seemed more than a little strange. In fact, Chichewa is strongly based on words for things that people see and encounter in daily life. Our translator had to get a bit creative and come up with ‘equivalent’ names for objects such as a robot (a doll in the Chichewa version), a turnip (a potato in the app), a dragon (she had to use a description meaning ‘a fierce animal’) or a fridge (replaced by a cupboard). There are also many more ‘technical’ words which don’t exist in traditional Chichewa, such as shapes. These are therefore normally given English names with a slight Chichewa accent (sikweya, trayango, rekitango and so on).

This is quite similar in Wolof: many items simply do not have a name in Wolof, or the words are unfamilar to most young people. Many items are therefore named in French instead, such as animals (giraffe), shapes (cercle) or fruits (banane). Above about 10, Wolof-speakers also tend to revert to French numbers instead of the more complex Wolof system (similar to the Chichewa – 5 and 1, 5 and 2…).

As with the uTalk app, Polish proved an especially problematic language for us too. One of the biggest issues was that in Polish the word for ‘you’ is dependent on gender. The translator mainly dealt with this by saying ‘we’ (e.g. Nauczyliśmy się/robiliśmy – we learned/were learning how to…), rather than addressing the child playing the app as male or female. It is also not usual to use prepositions such as ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ when describing the location of an object. e.g. instead of saying ‘the book is outside the cupboard’, Poles would normally say ‘the book is not in the cupboard’. Similarly to many other languages, some of the objects were also not very familiar: a cricket bat is not a well-known object, so it was translated as kijek – a little bat, and mangoes were translated as owoce – a fruit, as mangoes are not a ‘usual’ fruit in Poland – the same was the case with the Hungarian app, where we translated mango as gyumolc – also a generic word for fruit.

As with the uTalk app, Polish proved an especially problematic language for us too. One of the biggest issues was that in Polish the word for ‘you’ is dependent on gender. The translator mainly dealt with this by saying ‘we’ (e.g. Nauczyliśmy się/robiliśmy – we learned/were learning how to…), rather than addressing the child playing the app as male or female. It is also not usual to use prepositions such as ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ when describing the location of an object. e.g. instead of saying ‘the book is outside the cupboard’, Poles would normally say ‘the book is not in the cupboard’. Similarly to many other languages, some of the objects were also not very familiar: a cricket bat is not a well-known object, so it was translated as kijek – a little bat, and mangoes were translated as owoce – a fruit, as mangoes are not a ‘usual’ fruit in Poland – the same was the case with the Hungarian app, where we translated mango as gyumolc – also a generic word for fruit.

In Portuguese, there is no real way to distinguish between ‘more’ and ‘most’ or ‘less’ and ‘least’. Mais means both more and most, and menos less/least/fewer/fewest. This is also the case in Welsh: ‘bigger’ and ‘biggest’ translate to mwy and mwyaf respectively, but ‘more’ and ‘most’ also translate to mwy and mwyaf. The same goes for ‘smaller’/’smallest’ and ‘less’/’least’ (llai, lleiaf). On the other hand, there are different words for top and bottom shelves. Generally ‘top’ and ‘bottom’ are top and gwaelod but ‘top shelf’ and ‘bottom shelf’ are silff uchaf and silff usaf.

I was also intrigued to find out that in Amharic (an African language spoken in Ethiopia), they have a completely different system for telling the time: ‘1 o’clock’ does not mean lunch time, it in fact means ‘the first hour of the day’, i.e. when the sun comes up, and the rest of the day is counted from there. In fact, “Telling the time’ has been one of the hardest topics to localise, as our ideas of what happens at what time are not exactly international. Our French translator not only found the idea of eating a boiled egg for breakfast rather funny, but also pointed out that schools finish at 5 in France, not 3 as in the app, and a child would eat dinner at 7 or 8, not at 5 or 6! In Spain this is even funnier, as Spanish children regularly eat their dinner at 9 p.m., and go to sleep at 10 p.m. or perhaps later at the weekend or on holiday.

These are just a few of the language and cultural issues we’ve encountered on the maths translation project, and there are sure to be more! We have 10+ new languages ready to be released, and many more in the pipeline, so watch this space!

Alex

The maths apps are available from the App Store: Maths, age 3-5 and Maths, age 4-6.

The maths apps are available from the App Store: Maths, age 3-5 and Maths, age 4-6.

And also now available (in English only for the time being), Counting to 10, our first maths practice app, is on sale in the iTunes App Store for iPhone, iPod touch and iPad, and Google Play, for Android devices.

The challenges of translation

Over the last six months we’ve had our new free app uTalk translated into over 30 languages, and dealt with over 120 native language speakers who’ve either translated or performed the scripts. Along the way we’ve confronted many challenges which really emphasise how one language can be ambiguous whilst another is precise, and vice versa.

In English, for example, we can go to the shop and ask for a pepper without having to specify the colour, or order a boiled egg without stating whether it should be hard or soft; we refer to brothers and sisters without having to qualify their age; we talk about grandparents, uncles and aunts without saying which side of the family they are on and, perhaps most infuriatingly for non-native speakers (those inclined towards a bit of juicy gossip), we can refer to friends and partners without having to say whether they are male or female. We can be elusive and a little bit mysterious through the vagueness of the English tongue. This is not always the case in every language, and here are a few examples of what we’ve learnt so far:

– In Vietnamese, you don’t just have a brother or sister: there is no general word. Instead, you specifically have an older or younger brother or sister. In Basque, too, there is no generic word, but the difference depends on the gender of the speaker rather than age: my Mum’s word for her brother (neba) will be different to my Dad’s word for his brother (anaia).

– In Vietnamese, you don’t just have a brother or sister: there is no general word. Instead, you specifically have an older or younger brother or sister. In Basque, too, there is no generic word, but the difference depends on the gender of the speaker rather than age: my Mum’s word for her brother (neba) will be different to my Dad’s word for his brother (anaia).

– Danish has two words for a wall, depending on whether it is an outdoor, brick-built wall or an interior wall.

– In Polish, we debated the straightforward English phrase He scores (a goal), which can be translated with a variety of terms depending primarily on whether he scores visibly, in the eyes of the spectators, or definitely, after verification from the referee.

– The Romanians use two words for snow – one to describe the falling droplets, one to refer to the layer already on the ground.

As well as these difficulties in trying to get different languages to correspond to each other, we’ve come across some interesting stylistic issues which don’t exist in English:

– In languages such as Czech and Slovak, our translators worried over the best way to tell the time, since it is common to express twenty-five past two as five to half past two, a construction which may initially confuse learners who have never encountered it. (English speakers may also be surprised when they first learn the time in many Slavic languages, where quarter past four is, literally, quarter of the fifth, the implication being that we are in the fifth hour).

– In Chichewa, our translators opted for entirely different and equally valid counting systems: one went for the traditional Chichewa way of counting based on the numbers 1 to 5, followed by increasingly complex and lengthy sums which require quick thinking and an aptitude for arithmetic in everyday transactions; the other opted for the commonly used English loan words- twente eiti (28), faifi (5) etc. Both systems are equally used, understood and widespread in Malawi.

– Our Honduran consultant objected slightly to the inclusion of the word ketchup in the Latin American Spanish script, saying that la salsa de tomate would be more appropriate in his country. But this clashed with our Peruvian consultant’s advice, since ketchup is a widespread word in Peru and the salsa de tomate could refer to any other tomato-based sauce. Our Mexican translator chipped in that in Mexico ketchup is indeed commonly used, though catsup would be equally widespread… In the end, we settled on ketchup as the most generally acceptable in the largest number of places.

– Our Honduran consultant objected slightly to the inclusion of the word ketchup in the Latin American Spanish script, saying that la salsa de tomate would be more appropriate in his country. But this clashed with our Peruvian consultant’s advice, since ketchup is a widespread word in Peru and the salsa de tomate could refer to any other tomato-based sauce. Our Mexican translator chipped in that in Mexico ketchup is indeed commonly used, though catsup would be equally widespread… In the end, we settled on ketchup as the most generally acceptable in the largest number of places.

– In Polish, there is no good way to translate the phrases at the top of the stairs and at the bottom of the stairs: they would just say on the stairs in both cases. Part of the reason for this is the strange repetition you get if you specify at and on – na górze na schodach. The same odd-sounding repetition caused problems in the Spanish translation of I’m leaving tomorrow at eight in the morning, since the words for tomorrow and morning are identical, thus Me marcho mañana a las ocho de la mañana. It sounds so strange that people would prefer to leave out the first mañana.

These are just a few of the little points of interest we encounter on a regular basis in our translation project, and we’re looking forward to finding more and sharing them with you!

Nat

uTalk is now available from the App Store – it’s free to download and includes basic words in 25 languages, with options to upgrade for more vocabulary.

uTalk is now available from the App Store – it’s free to download and includes basic words in 25 languages, with options to upgrade for more vocabulary.